Two new eriophyoid mite species of the genus Leipothrix Keifer (Acariformes, Eriophyoidea) from Russian Siberia and eastern USA

Chetverikov, Philipp E.  1

; Kudryavtzev, Andrey T.2

and Amrine, James W.

1

; Kudryavtzev, Andrey T.2

and Amrine, James W.  3

3

1✉ Zoological Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya Nab. 1, Saint-Petersburg, 199034, Russia & X-BIO Institute, University of Tyumen, 6 Volodarskovo Street, Tyumen, 625003, Russia.

2Zoological Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya Nab. 1, Saint-Petersburg, 199034, Russia & Saint-Petersburg State Agrarian University, Peterburgskoe shosse 2, Pushkin, St. Petersburg, 196601, Russia.

3West Virginia University, Division of Plant and Soil Sciences, P.O.Box 6108, Morgantown, WV 26506-6108, USA.

2025 - Volume: 65 Issue: 4 pages: 1246-1263

https://doi.org/10.24349/5385-bq5rZooBank LSID: 5247B31D-69F2-40DA-B27E-8C1A75BD6546

Original research

Keywords

Abstract

Introduction

Eriophyoid mites (Eriophyoidea) are extremely miniaturized, morphologically reduced phytoparasitic chelicerates (Lindquist 1996) with the smallest known arthropod genomes, ranging from ~32.5 to 47 Mb (Greenhalgh et al. 2020; Klimov et al. 2022; Shao et al. 2025). Fossil-calibrated estimates place the origin of Eriophyoidea in the Devonian (~376 Ma), when this group apparently diverged from the soil-dwelling Nematalycidae (Bolton et al. 2017, 2023) and shifted to parasitizing early land plants (Sukhareva 1994; Klimov et al. 2025). Eriophyoid mites exhibit striking morphological stasis over millions of years; Triassic amber specimens, probably linked to the extinct gymnosperm family Cheirolepidiaceae, are virtually indistinguishable from modern conifer-associated taxa (Schmidt et al. 2010, Sidorchuk et al. 2014). This evolutionary stability may reflect both extreme genomic reduction and the highly simplified body plan of Eriophyoidea, which constrain morphological innovation (Greenhalgh et al. 2020).

Recent reexamination of the unique Devonian Rhynie Chert fossil Protoacarus (Endeostigmata) helped establish that the Eriophyoidea crown-group diversified around ~305 Ma (Klimov et al. 2025). Despite advances in molecular methods, phylogenetic relationships among major extant lineages of eriophyoid mites remain unresolved (Li et al. 2014; Xue et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2024; Gankevich, Chetverikov 2025). Currently, ~5 000 species and ~300 genera of eriophyoid mites are described. Most genera frequently resolve as non-monophyletic in molecular studies. This is expected, because their diagnoses are often based on homoplastic and plesiomorphic characters (Craemer 2010), meaning they represent diverse morphotypes rather than true evolutionary lineages (e.g., Aceria, Cecidophyopsis, and Phytoptus) (Li et al. 2014; Chetverikov et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2024; Gankevich, Chetverikov 2025). Due to the ambiguity of certain diagnostic characters, current generic assignments often depend on researchers' subjective interpretations, potentially resulting in incorrect genus-species combinations. This situation highlights limitations in the current diagnostic system for eriophyoid taxonomy and underscores the need for rigorous phylogenetic and systematic studies of this group.

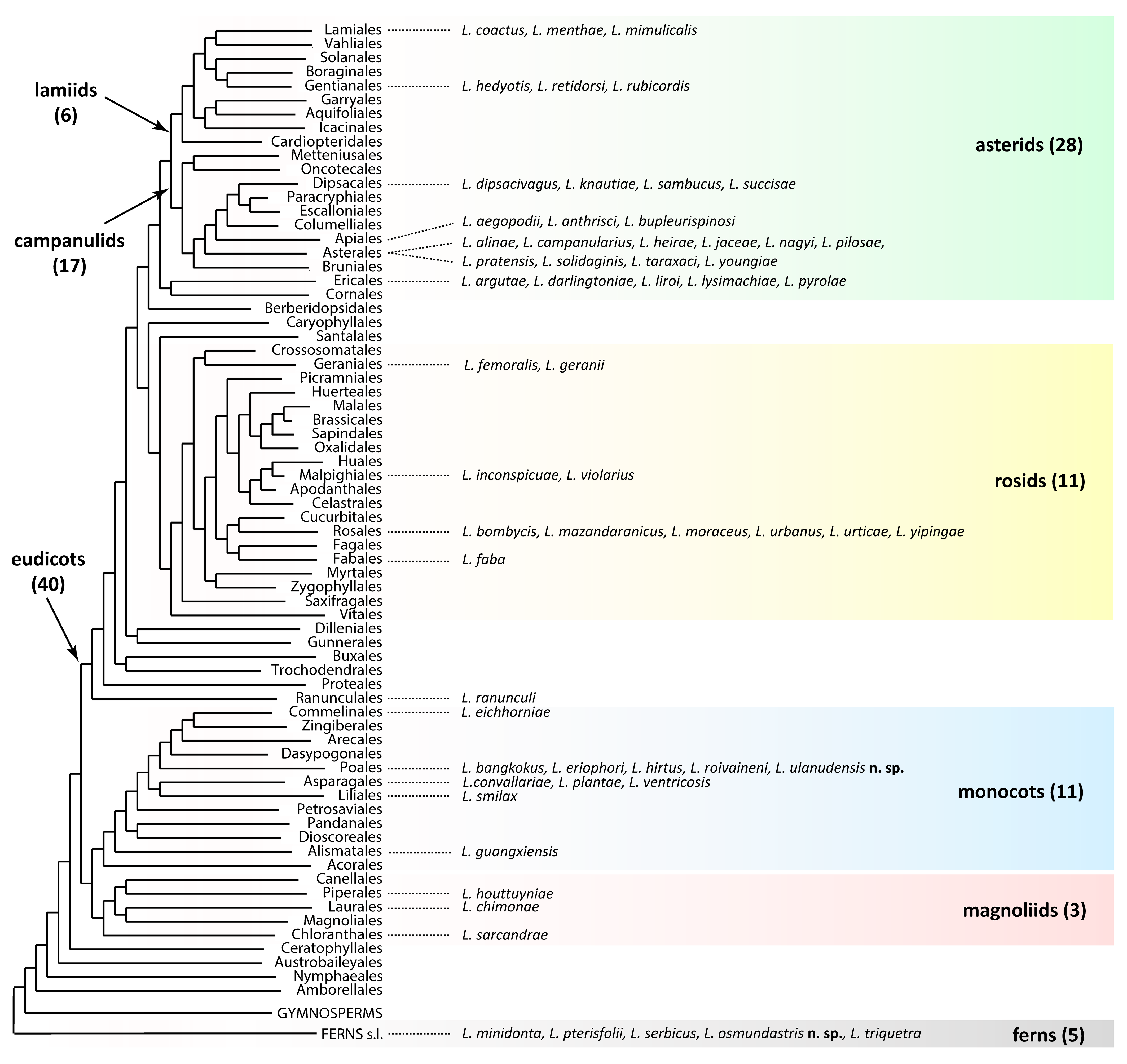

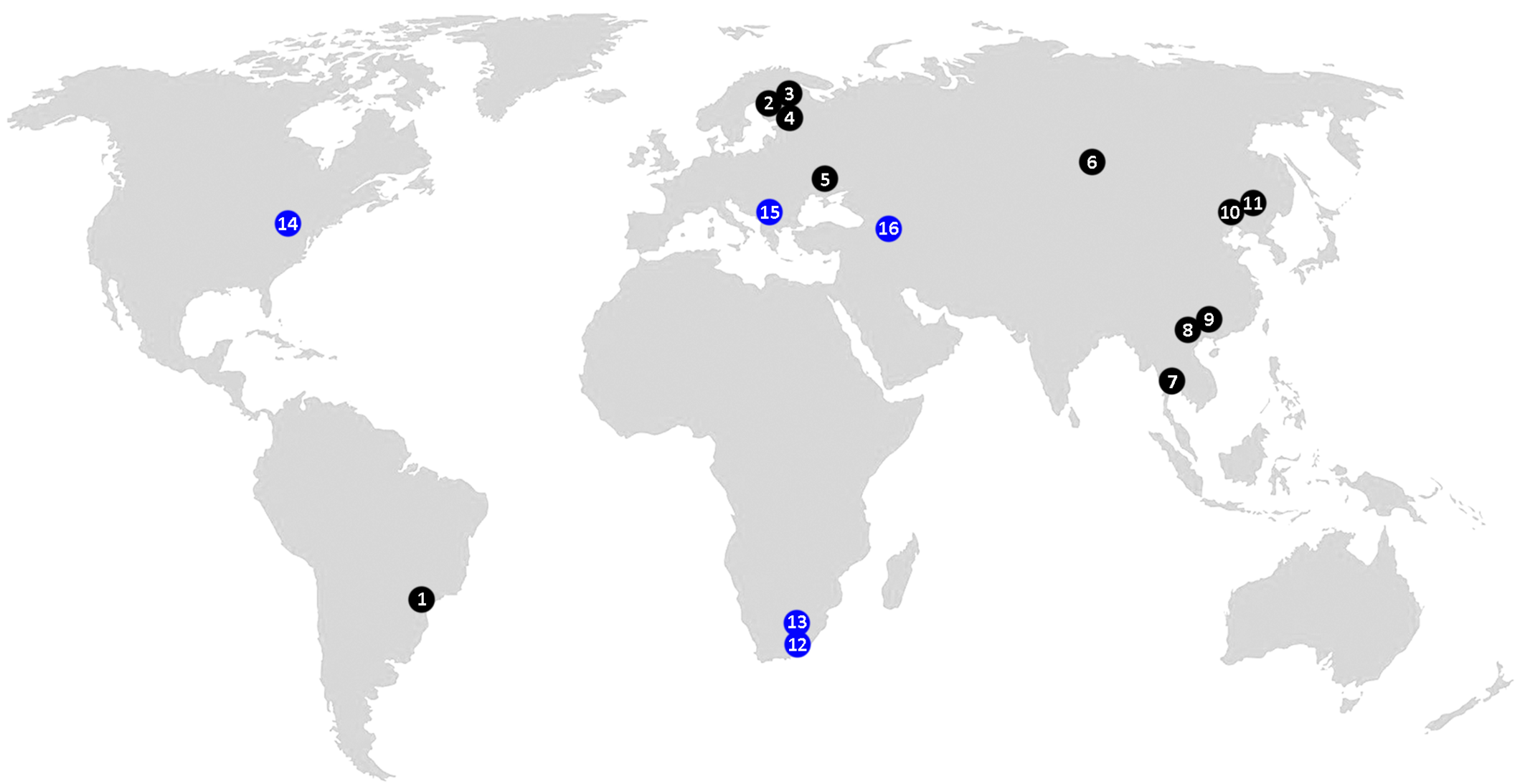

Leipothrix Keifer, 1966 is a morphologically well-defined eriophyoid genus, typically easy to identify at the generic level in samples by a combination of three distinct diagnostic characters: (1) bifurcated pedipalp setae d, (2) three longitudinal opisthosomal ridges, and (3) absence of femoral setae bv I and II (Amrine et al. 2003). According to our updated estimates, this genus comprises 59 species (including two new species described in this paper) associated with two major lineages of higher vascular plants: angiosperms (54 spp., ~92%) and ferns (5 spp., ~8%) (Figure 1). The only Leipothrix species previously described from gymnosperms, L. juniperensis (Xue & Yin, 2020), was recently excluded from Leipothrix (Chetverikov et al. 2023a) and reclassified in Glossilus Navia & Flechtmann, 2000 (Yao et al. 2024). All described Leipothrix spp. are vagrant, typically living on the lower leaf surface and causing no conspicuous damage to their host plants. Except for two species described from ferns in South Africa and one species from an invasive monocot in Brazil (Figure 2), all other Leipothrix spp. were found in the Northern Hemisphere, where they are mainly associated with Palearctic herbaceous plants. About one quarter of Leipothrix spp. (19 spp., ~32%) are associated with early-derivative plant clades (ferns—5 spp., magnoliids—3, and monocots—11). The remaining 40 species (~68%) occur on eudicots, with the highest diversity found on the order Asterales (11 spp., ~19% of the total) (Figure 1).

Approximately half of currently recognized Leipothrix species were described in the mid-20th century. After the refinement of the generic diagnosis by Amrine et al. (2003), the rate of description notably increased, with a large series of new species emerging mainly from Asia in the last decade (Tan et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2017; Lotfollahi & de Lillo 2017; Ripka & Kiss (2020); Han et al. 2025; Varandi et al. 2020; Hao et al. 2023; Xiao et al. 2025). Molecular studies on Leipothrix are still limited, consisting of a few taxonomic papers with fragmentary barcode sequences (Hao et al. 2023; Pińkowska & Lewandowski 2024) and one mitogenomic study (Chetverikov et al. 2023a). Despite limited taxon sampling, the latter reported a distinctive mitochondrial gene order and confirmed the monophyly of Leipothrix.

The validity of many described Leipothrix species requires verification because of poor descriptions and inadequate illustrations (e.g., L. fabus Halawa & Mohamed, 2015). Seasonal morphological dimorphism in females (deuterogeny) has been documented in Leipothrix (Han et al. 2025), raising the possibility that deutogynes and protogynes were mistakenly described as distinct species (e.g., L. eriophyori and L. roivaineni) (Chetverikov 2005). Furthermore, many phyllocoptine species (e.g., some Epitrimerus spp. described by J.I. Liro, H. Roivainen, and other acarologists in the 20th century) morphologically align with the generic diagnosis of Leipothrix (Amrine et al. 2003; Chetverikov 2005). Following reinvestigation, some were transferred to Leipothrix (Chetverikov 2005; Jǒcić and Petanović 2012; Pińkowska & Lewandowski 2024), while others await validation of their generic placement. These taxonomic challenges highlight the need for a comprehensive revision of Leipothrix, a difficult task given the genus's broad geographic distribution and species diversity.

In this paper we describe two new Leipothrix species collected in 2011–2012 from the eastern United States (on the fern Osmundastrum cinnamomeum, Osmundaceae) and Russian Siberia (on the sedge Carex pediformis, Cyperaceae). A distribution map of Leipothrix species associated with ferns and monocots (Figure 2) shows that these are the first continental records of the genus from ferns in North America and from monocots in northern Asia. Since this study was based on old slide-mounted specimens, we were unable to characterize the new taxa molecularly through sequencing barcode genes. Yet we obtained high-quality microphotographs and, for the first time, observed putative multiple spermatophore-like structures inside males of one Leipothrix species.

Material and methods

Collection and morphological measurements

Eriophyoid mites were collected from ferns in West Virginia, USA, in August 2012 and in Buryatia (Russia) in 2011 using a fine minuten pin and a stereomicroscope. They were mounted in modified Berlese medium with iodine in the laboratory in the USA and in Hoyer's medium under field conditions in Russia, and cleared on a heating block at 94 °C for 5 hours (Amrine & Manson 1996). The slide-mounted specimens were examined with differential interference contrast light microscopy (DIC LM) and phase-contrast light microscopy (PC LM) in the Laboratory of Parasitic Arthropods of the Zoological Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences (ZIN RAS). In the species descriptions, measurements of the holotype (female) are presented along with ranges based on paratype females; for deutogyne females and males, only ranges are given. All measurements are given in micrometers (μm) as lengths unless stated otherwise. Classification and terminology of eriophyoid genital anatomy and external morphology follow that of Amrine et al. (2003), Chetverikov (2014), and Lindquist (1996) respectively. Drawings of the mites were produced with the aid of a video projector, as described by Chetverikov (2016b).

Confocal microscopy

Exoskeletons of Leipothrix specimens mounted in Hoyer's medium were investigated using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) with a spectral confocal and multiphoton system Leica TCS SP2 (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) with the same settings of the confocal microscope as described by Chetverikov (2014). Image stacks were rendered three-dimensionally using the reconstruction software Amira®5.3.2 (FEI Visualization Science Group, Hillsboro, OR, USA).

Results

Superfamily Eriophyoidea Nalepa 1898

Family Eriophyidae Nalepa 1898

Subfamily Phyllocoptinae Nalepa 1892

Tribe Phyllocoptini Nalepa 1892

Genus Leipothrix Keifer 1966

Leipothrix osmundastris n. sp.

ZOOBANK: 9DB3A4A7-9E17-42E1-9725-07F5C4EB5AD0 ![]()

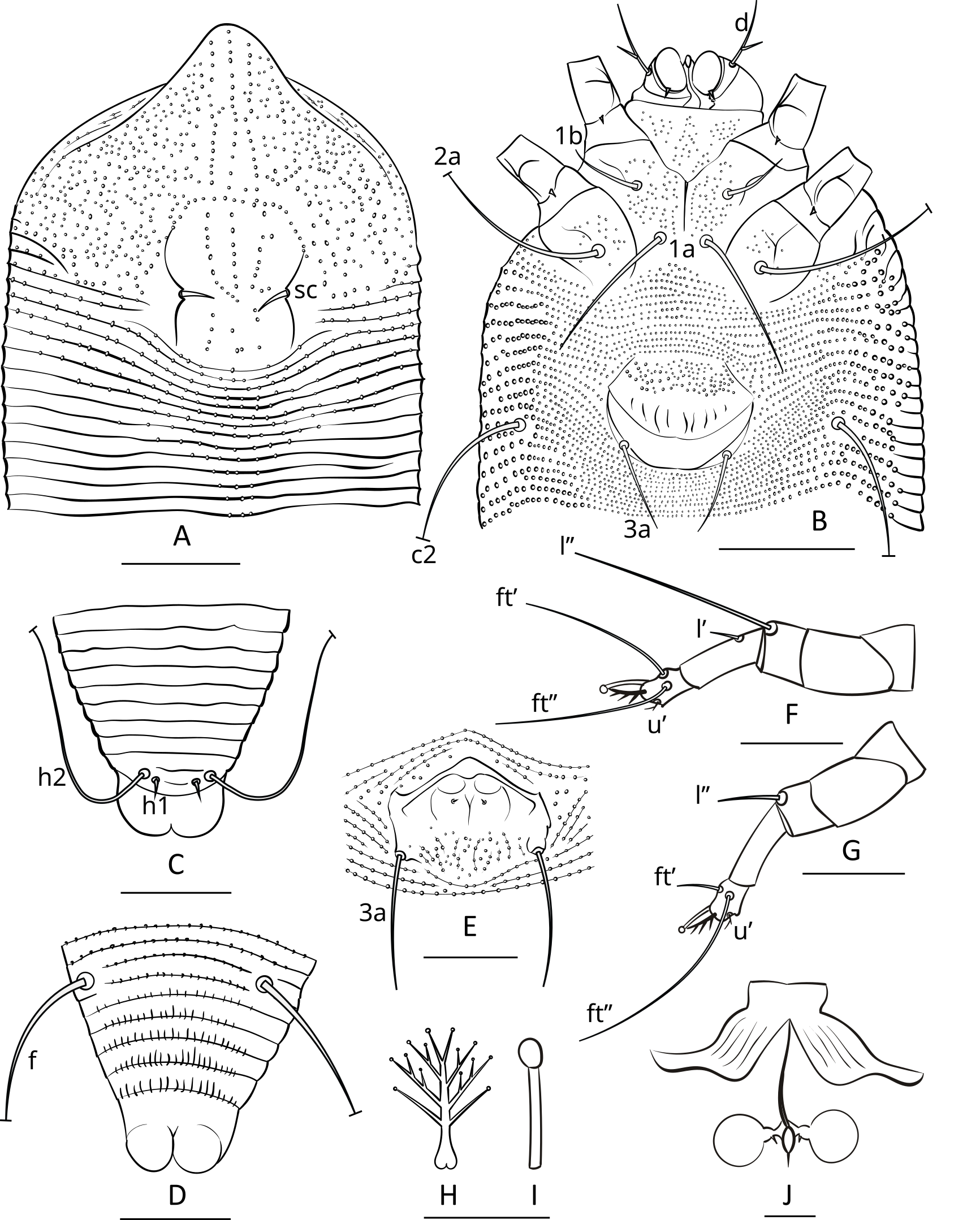

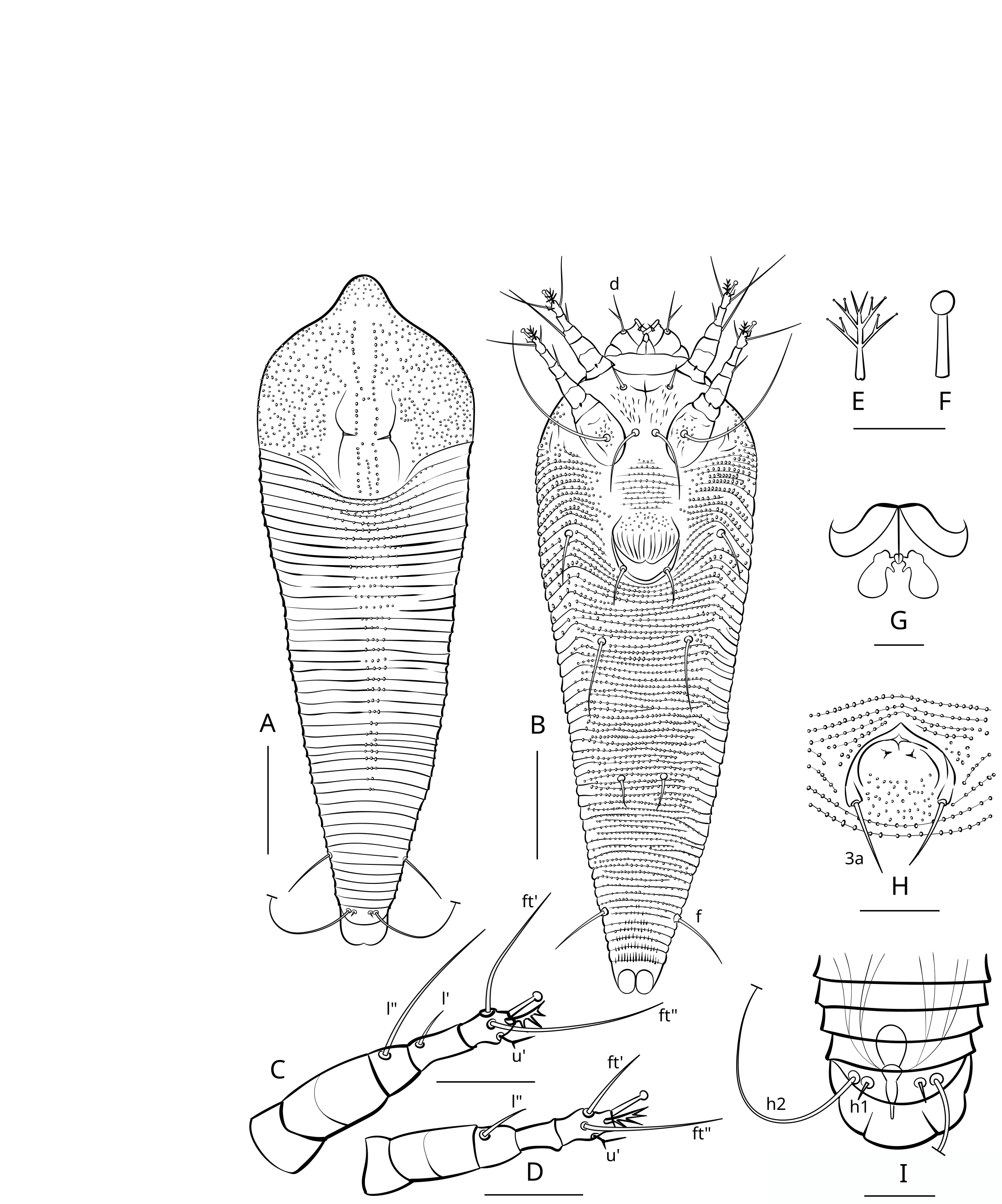

Figures 3, 4, 5.

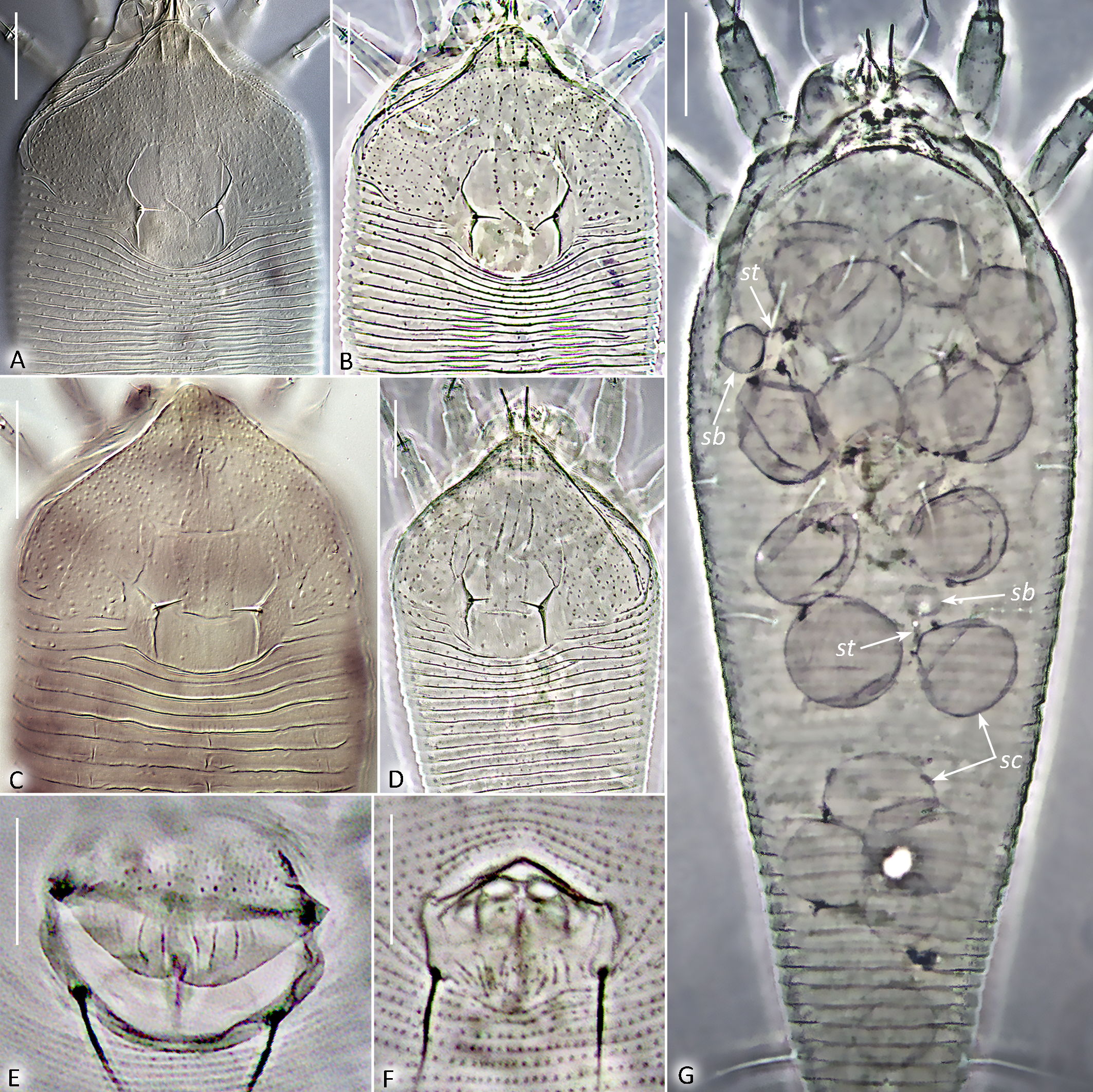

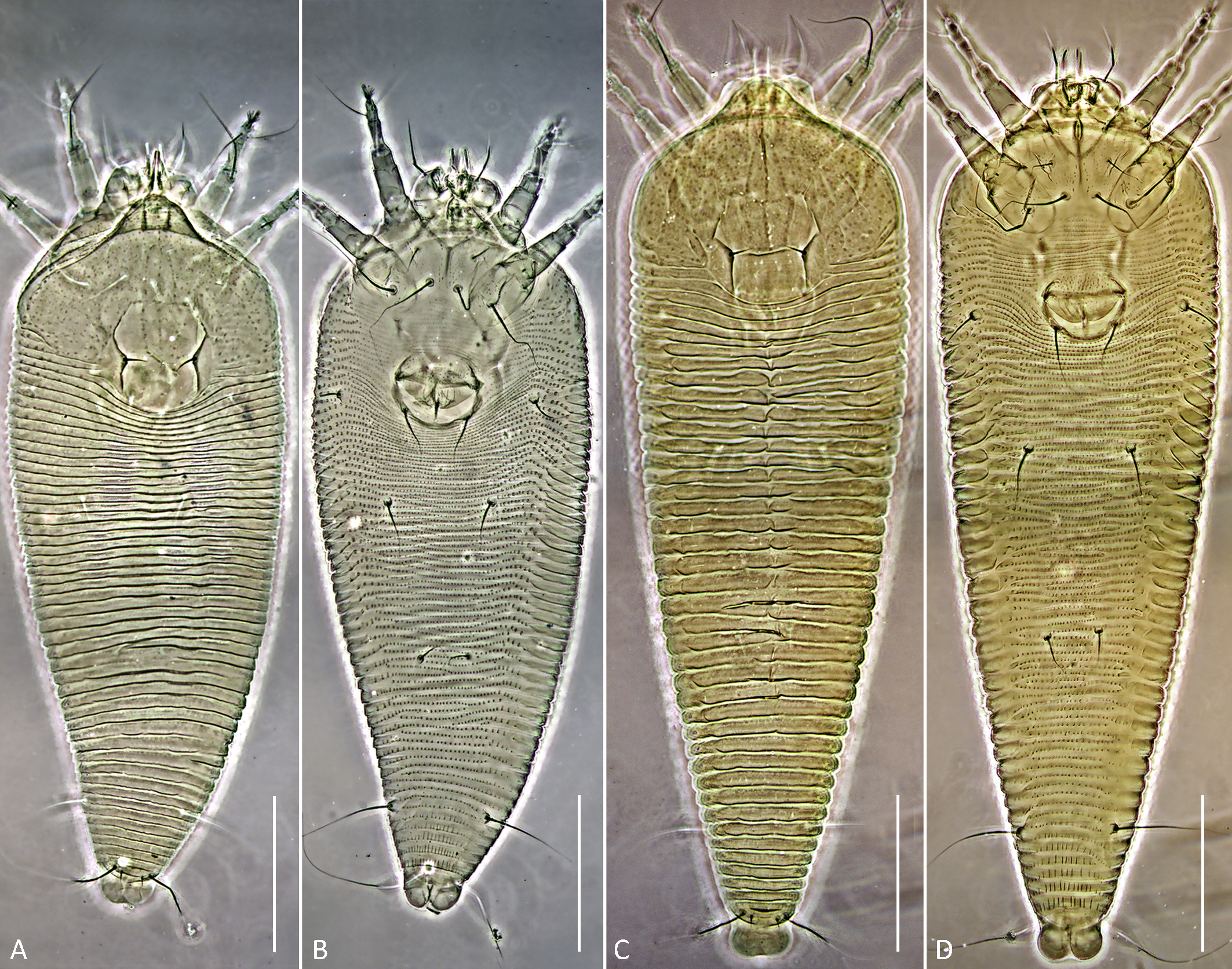

Protogyne female (n=8; Figures 3; 4 A, B, C, E; 5 A, B)

Body — Fusiform, 198 (193–202), 69 (67–70) wide, light orange.

Gnathosoma — 20 (18–22), projecting down and slightly forward, pedipalp coxal seta (ep) 2 (1–3), dorsal pedipalp genual seta (d) branched, consisting of basic and accessory branches, 16 (14–16), cheliceral stylets 15 (13–17). Suboral plate 10 (9–11), 14 (12–16) wide.

Prodorsal shield — 58 (56–59), 66 (63–68) wide, subrhomboidal, with broad-based and apically rounded frontal lobe 12 (10–13). The frontal lobe is rounded dorsally, with a lumpy somewhat irregular anterior margin, and flat on the ventral surface with a fine sculpture of concentric lines dotted with small nodules. The prodorsal shield extends posteriorly as a lobe, indenting the first 5–7 annuli which form a short middorsal opisthosomal ridge. The entire shield surface is covered with nodules that vary in size or may be more uniform. All specimens have a distinct marginal line extending from the edge of the frontal lobe around the margin of the shield. Some specimens show weak median, admedian and submedian lines linking small nodules; these are absent in many others. In some specimens, groups of small nodules form short ridges scattered over the prodorsal shield. The lateral prodorsal shield is flexible cuticle, undulating, with fine lines of nodules radiating from the shield to the epicoxae. The scapular tubercles are plicate and embedded in the scapular ridges. The scapular setae (sc) are 6 (5–6), usually curved mesally or up, 19 (18–19) apart,

Coxigenital region — With 14 (11–15) semiannuli between coxae and genitalia. The coxal plates are covered with fine tubercles, which are more numerous in coxal plates II. Anterolateral setae on coxisternum І (1b) 14 (11–17), 15 (14–15) apart, proximal setae on coxisternum І (1a) 32 (29–34), 8 (7–9) apart, proximal setae on coxisternum ІІ (2a) 41 (38–47), 27 (26–28) apart. Epicoxal area with faint subparallel microtuberculate striae. Prosternal apodeme 9 (8–10).

Female genitalia — Genital coverflap 20 (18–21) long, 24 (22–25) wide, microtuberculate in basal part and with 8 (7–9) longitudinal ridges in distal part; setae 3a 15 (13–17) long, 17 (16–18) apart. Spermathecae subspherical, 5 (4–6) in diameter, with tiny spermathecal process of about 0.5 µm; anterior genital apodeme subtrapezoidal, with 8–10 subparallel ridges.

Leg I — 33 (33–34), femur 11 (10–11), with three distinct ventral ridges forming a wide trident fork, basiventral femoral seta (bv) absent; genu 6 (5–6), antaxial genual setae (l″) 23 (20–25); tibia 8 (7–8), paraxial tibial setae (l′) 14 (12–15); tarsus 6 (5–6), paraxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft′) 14 (13–15), antaxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft″) 18 (16–20), paraxial unguinal tarsal setae (u′) 2 (2–3), notably angled and with short accessorial branch; tarsal empodium (em) 5 (5–6), simple, 4-rayed; tarsal solenidion (ω) 6 (5–6), distally with large subspherical knob.

Leg ІІ — 32 (31–34), femur 11 (9–11), with three distinct ventral ridges forming a wide trident fork, basiventral femoral seta (bv) absent, genu 6 (5–6), antaxial genual setae (l″) 6 (5–7); tibia 6 (5–7), tarsus 6 (6–7), paraxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft′) 4 (3–5), antaxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft″) 19 (18–21), paraxial unguinal tarsal setae (u′) 2 (2–3), notably angled and with short accessorial branch; tarsal empodium (em) 5 (5–6), simple, 4-rayed; tarsal solenidion (ω) 6 (5–6), distally with large subspherical knob.

Opisthosoma — With 50 (48–51) dorsal annuli, forming weak medial ridge and two very indistinct lateral ridges. About 5–6 dorsal annuli behind posterior margin of prodorsal shield and medial opisthosomal ridge microtuberculate forming a distinct subtriangular microtuberculate area on dorsal opisthosoma. Ventrally, opisthosoma with 89 (84–92) microtuberculate ventral annuli. Setal lengths: c2 14 (12–15), d 21 (19–22), e 10 (9–10), f 26 (24–27), h1 3 (2–3), h2 47 (45–52). Distances between setae: 15 (14–17) annuli between c2 and d, 25 (24–28) annuli between d and e, 19 (19–22) annuli between e and f, 5 (5–6) annuli between f and h1, telosomal annuli smooth dorsally and with elongated microtubercles ventrally.

Deutogyne female (n=11; Figures 4 C; 5 C, D)

Body — Fusiform, 230–254, 72–77 wide, dark orange or brown.

Gnathosoma — 21–26, projecting down and slightly forward, pedipalp coxal seta (ep) 1–3, dorsal pedipalp genual seta (d) branched, consisting of basic and accessory branches, 16–19, cheliceral stylets 17–19. Suboral plate 10–11, 17–19 wide.

Prodorsal shield — 59–61, 66–69 wide, subrhomboidal, with broad-based and apically rounded frontal lobe 10–13, which is dorsally rounded with a flat ventral surface, marked with concentric lines and nodules as in the protogyne. Markings in deutogynes are stronger than in protogynes. Median line present in mid-shield, admedian lines distinct and curved laterally. A cross-line curves across the admedian and median lines connecting to the anterior part of each scapular ridge. Nodules are present over the entire prodorsal shield, larger laterally, smaller medially. Scapular tubercles are darker, more plicate than in the protogyne, 19–21 apart, scapular setae (sc) 5–6, directed up or mesally.

Coxigenital region — With 13–17 semiannuli between coxae and genitalia. The coxal plates are covered with fine tubercles, which are more numerous in coxal plates II. Anterolateral setae on coxisternum І (1b) 11–14, 14–15 apart, proximal setae on coxisternum І (1a) 28–36, 7–9 apart, proximal setae on coxisternum ІІ (2a) 39–47, 25–28 apart. Epicoxal area with faint subparallel microtuberculate striae. Prosternal apodeme 9–11.

Female genitalia — Genital coverflap 17–20, 22–25 wide, microtuberculate in basal part and with 7–9 longitudinal ridges in distal part; setae 3a 14–17, 16–18 apart. Internal genitalia similar to those of protogyne female.

Leg I — 34–37, femur 10–13, with three distinct ventral ridges forming a wide trident fork, basiventral femoral seta (bv) absent; genu 6–7, antaxial genual setae (l″) 26–29; tibia 8–9, paraxial tibial setae (l′) 5–7; tarsus 6–7, paraxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft′) 15–19, antaxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft″) 19–22, paraxial unguinal tarsal setae (u′) 2–3, distinctly angled and with short accessorial branch; tarsal empodium (em) 5–6, simple, 4-rayed; tarsal solenidion (ω) 5–6, distally with large subspherical knob.

Leg ІІ — 32–35, femur 11–12, with three distinct ventral ridges forming a wide trident fork, basiventral femoral seta (bv) absent, genu 5–6, antaxial genual setae (l″) 7–10; tibia 7–8, tarsus 6–7, paraxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft′) 19–21, antaxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft″) 3–5, paraxial unguinal tarsal setae (u′) 1–2, notably angled and with short accessorial branch; tarsal empodium (em) 5–6, simple, 4-rayed; tarsal solenidion (ω) 5–6, distally with large subspherical knob.

Opisthosoma — With 48–51 smooth dorsal annuli, forming distinct medial ridge and two faint lateral ridges. Ventrally opisthosoma with 90–97 microtuberculate ventral annuli. Setal lengths: c2 16–21, d 18–23, e 11–16, f 29–33, h1 2–3, h2 50–56. Distances between setae: 17–20 annuli between c2 and d, 23–28 annuli between d and e, 20–24 annuli between e and f, 5–6 annuli between f and h1, telosomal annuli smooth dorsally and with elongated microtubercles ventrally.

Remarks — The females interpreted here as protogynes and deutogynes coinhabited in mixed population in the same host plant and were collected in August – the end of warm season at the collecting site. The protogynes were light orange and perfectly cleared in slides while deutogynes were dark orange or brown and contained dark material inside the body which was hard to dissolve in Hoyer's medium. Both female forms share identical ornamentation of the prodorsal shield. The most distinct differences between them are in body size, width of suboral plate, length of setae, and topography of dorsal opisthosomal annuli (Table 1).

Download as

Character

Protogyne female

Deutogyne female

Length of body

193–202

230–254

Width of body

67–70

72–77

Width of suboral plate

12–16

17–19

Length of l’ I

2–3

5–7

Length of l’’ II

5–7

7–10

Topography of dorsal opisthosomal annuli

5–6 anteriormost dorsal annuli and medial opisthosomal ridge microtuberculate

dorsal annuli smooth

Male (n=6, Figures 3 E; 4 D, F, G)

Body — Fusiform, 154–174, 52–57 wide, light orange.

Gnathosoma — 16–17, projecting down and slightly forward, pedipalp coxal seta (ep) 1–2, dorsal pedipalp genual seta (d) angled consisting of basic and accessory branches, 18–20, cheliceral stylets 14–17.

Prodorsal shield — 44–49, including length of 6–7 frontal lobe, 50–54 wide, design similar to that of female but more distinct. Frontal lobe smaller than that of female, lateral margin more of a straight line to the rear; underside of frontal lobe flat, marked with concentric lines and small nodules (Figure 4G, top). Median and admedian lines close together at the frontal lobe, becoming more widely spaced at their posterior termination between sc. Anterior scapular ridge line less distinct, shorter, ending at about midshield. The plicate scapular tubercles more distinct, darker in color, located ahead of rear shield margin, 14–17 apart, scapular setae (sc) 4–5, directed mesally. Very fine striations cover the entire shield.

Coxigenital region — With 17–20 semiannuli between coxae and genitalia. Coxal plates microtuberculate, anterolateral setae on coxisternum І (1b) 9–11, 13–14 apart; proximal setae on coxisternum І (1a) 20–29, 6–7 apart; proximal setae on coxisternum ІІ (2a) 20–25, 16–20 apart. Prosternal apodeme 10–12.

Leg I — 34–39, femur 10–12, basiventral femoral seta (bv) absent; genu 6–7, antaxial genual setae (l″) 19–23; tibia 10–11, paraxial tibial setae (l′) 3–4; tarsus 6–7, paraxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft′) 10–12, antaxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft″) 15–17, paraxial unguinal tarsal setae (u′) 2–3, angled; tarsal empodium (em) 4–5, simple, 3-rayed; tarsal solenidion (ω) 5–6, with large spherical knob.

Leg ІІ — 33–36, femur 10–12, basiventral femoral setae (bv) absent; genu 5–6, antaxial genual setae (l″) 8–10; tibia 8–9; tarsus 6–7, paraxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft′) 3–4, antaxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft″) 16–18, paraxial unguinal tarsal setae (u′) 1–2, angled; tarsal empodium (em) 4–5, simple, 3-rayed, tarsal solenidion (ω) 5–6, with large spherical knob.

Genital area — 13–17, 15–18 wide, eu present but very short, 3a 14–18, 12–15 apart, genital cuticle flanked by tubercles of 3a with short ridges and microtubercles.

Opisthosoma — Dorsally with 40–42 annuli, shaped and microtuberculate similar to those in protogyne female; ventrally with microtuberculate 74–83 annuli. Setal lengths: c2 9–13, d 16–19, e 11–13, f 22–25, h1 2–3, h2 30–39. Distances between setae: 13–17 annuli between c2 and d, 16–20 annuli between d and e, 17–20 annuli between e and f, 5–7 annuli between f and h1.

Remarks — Three of the six investigated males contained groups of 12–20 spherical structures, ~15 µm in diameter, inside the body (Figure 4G). Under higher magnification, additional smaller subspherical pad-like structures, ~5 µm in diameter, connected via thin filamentous stalks to the larger spheroids were observed. These structures were not observed in females. We propose they are either spermatophores (comprising a sperm capsule, stalk, and pad-like base) or previously unreported male-specific symbionts or parasite eggs.

Host plant

Host plant — Osmundastrum cinnamomeum (L.) C. Presl 1848 (Polypodiopsida: Osmundales: Osmundaceae).

Relation to the host — Vagrant on lower surface of frond pinnae causing no visible damage.

Type locality and material

Type locality — USA: West Virginia, Cooper's Rock State Forest, 39°39′20.3″N 79°47′06.5″W.

Type material — Holotype female (encircled) and paratypes on slide E272 collected on 7 August 2012 at the type locality, coll. J. Amrine and P. Chetverikov. Type material deposited in Acarological Collection of ZIN RAS. Some specimens are deposited in the private collection of J. Amrine.

Etymology

The species epithet osmundastris is an adjective, gender feminine, derived from the generic name of the host plant, Osmundastrum.

Differential diagnosis

Leipothrix osmundastris n. sp. is most similar to the members of a small group of Leipothrix associated with ferns (Figure 1). This group includes two species from South Africa (L. minidonta, Smith Meyer 1990 and L. triquetra, Smith Meyer 1990), one from Europe (L. serbicus Petanović, 1999), and one from Western Asia (L. pterisfolii Lotfollahi & de Lillo, 2017). Among them, the new species is most similar to L. pterisfolii, based on the general similarity of prodorsal shield design and dorsal opisthosomal microtuberculation pattern. The main differences between L. osmundastris n. sp. and L. pterisfolii concern presence/absence of cell-like network on prodorsal shield, ornamentation of distal part of genital coverflap and ventral femora, number of opisthosomal annuli and lengths of setae sc and palp seta d (Table 2).

Download as

Character

L. pterisfolii Lotfollahi & de Lillo 2017

L. osmundastris n. sp.

L. ulanudensis n. sp.

Ornamentation of prodorsal shield

consisting of granulate lines forming a cell-like network

cell-like network absent or very indistinct and then observed only anterolateral part of prodorsal shield (Figure 4A, 5A)

cell-like network absent or very faint and present only in lateral area of prodorsal shield (Figure 7A, 7C)

Ornamentation of distal part of genital coverflap

smooth

with 7–9 longitudinal ridges

with 11–13 longitudinal ridges

Ornamentation of ventral femur I and II

smooth

with three distinct ventral ridges forming a wide trident fork (Figure 3B)

with indistinct circular ridge putatively marking secondary division of femur into two subsegments (Figure 6 A,C,D; Figure 7 B,D)

Number of empodial rays

4

4

3

Number of dorsal annuli

52– 59

48–51

41–46

Number of ventral opisthosomal annuli

65– 81

84–92

74–78

Length of sc

10–14

5–6

2–4

Length of palp d

18–23

14–16

9–11

Host plant

Polypodium vulgare L. (Polypodiaceae) and Gymnocarpium dryopteris (L.) Newman (Cystopteridaceae)

Osmundastrum cinnamomeum (L.) C. Presl 1848 (Osmundaceae)

Carex pediformis Mey, 1831 (Poales: Cyperaceae)

Distribution

Iran

USA

Siberia (Russia)

Leipothrix ulanudensis n. sp.

ZOOBANK: 08E101CC-2D7C-44BC-8959-7020A370BD0D ![]()

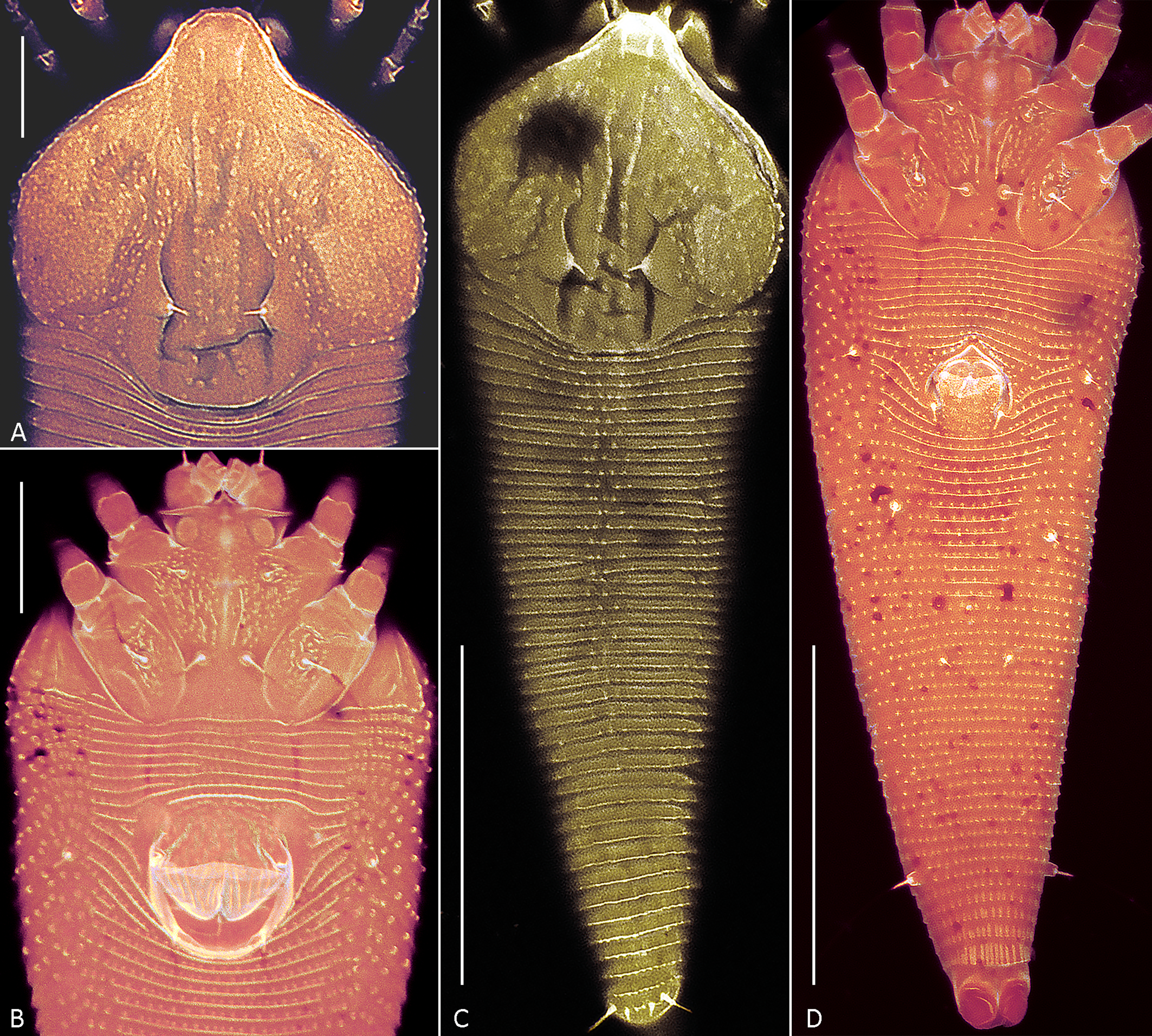

Figures 6, 7.

Female (n=7)

Body — Fusiform, 191 (172–200), 64 (61–66) wide, light orange.

Gnathosoma — 18 (17–20), projecting down and slightly forward, pedipalp coxal seta (ep) 1 (1–3), dorsal pedipalp genual seta (d) branched, consisting of basic and accessory branches, 10 (9–11), cheliceral stylets 18 (17–19).

Prodorsal shield — 62 (60–64), 63 (60–63) wide, subrhomboidal, with broad-based and apically rounded frontal lobe 13 (11–16). The entire shield surface is covered with microtubercles that are larger in the center and gradually become smaller towards the edges. The median line is either absent or, in some specimens, situated near posterior margin of prodorsal shield and present as indistinct short ridge marked with small microtubercles. The admedian lines are distinct and subparallel, diverging posteriorly while remaining parallel or slightly convergent anteriorly, and are covered with prominent microtubercles. Submedian lines are not visible as distinct structures. The lateral cuticle of the prodorsal shield shows very weak reticulation with variable undulating, rounded patterns formed by fine microtubercles. The scapular setae (sc) are situated on broad-based cuticular folds located notably ahead of the rear shield margin, 15 (13–15) apart, scapular setae (sc) 2 (2–4), directed up or toward each other.

Coxigenital region — with 8 (7–10) semiannuli between coxae and genitalia. The coxal plates are striated and covered with fine tubercles that are more distinct in coxal plates II. Anterolateral setae on coxisternum І (1b) 5 (5–9), 12 (12–15) apart, proximal setae on coxisternum І (1a) 13 (9–14), 6 (5–9) apart, proximal setae on coxisternum ІІ (2a) 35 (28–35), 23 (22–24) apart. Epicoxal area microtuberculate. Prosternal apodeme 15 (13–18).

Female genitalia — Genital coverflap 15 (13–17) long, 20 (19–22) wide, microtuberculate in basal part and with 12 (11–13) longitudinal ridges in distal part; setae 3a 12 (11–12) long, 13 (12–14) apart. Spermathecae tear-drop shaped, 5 (4–6) long, with tiny spermathecal process; anterior genital apodeme subtrapezoidal, smooth or with faint subparallel ridges in some specimens.

Leg I — 28 (26–29), femur 10 (9–10), with indistinct circular ridge putatively marking secondary division of femur into two subsegments, basiventral femoral seta (bv) absent; genu 5 (4–5), antaxial genual setae (l″) 22 (18–22); tibia 6 (5–6), paraxial tibial setae (l′) 4 (3–6); tarsus 5 (4–5), paraxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft′) 12 (11–14), antaxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft″)13 (13–15), paraxial unguinal tarsal setae (u′) 1 (1–2), notably angled with short accessorial branch; tarsal empodium (em) 4 (4–5), simple, 3-rayed; tarsal solenidion (ω) 5 (4–5), distally with large subspherical knob.

Leg ІІ — 24 (24–27), femur 8 (8–10), with indistinct circular ridge putatively marking secondary division of femur into two subsegments, basiventral femoral setae (bv) absent; genu 5 (3–5), antaxial genual setae (l″) 4 (3–4); tibia 5 (4–6), paraxial tibial setae (l′) absent; tarsus 5 (4–5), paraxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft′) 3 (1–3), antaxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft″) 15 (14–16), paraxial unguinal tarsal setae (u′) 1 (1–2), notably angled with short accessorial branch; tarsal empodium (em) 4, simple, 3-rayed, tarsal solenidion (ω) 4 (4–5), distally with large subspherical knob.

Opisthosoma — With 41 (41–46) dorsal annuli, that are smooth laterally and with microtubercles midway. The dorsal annuli form a median longitudinal ridge (fading above setae f) and two very faint lateral ridges. In most slide-mounted specimens, the lateral ridges are scarcely discernible as they are aligned almost precisely with the lateral margin of the opisthosoma. Ventrally opisthosoma with 74 (74–78) microtuberculate ventral annuli. Setae c2 6 (4–6) on ventral annulus 15 (13–16); setae d 15 (11–15) on ventral annulus 27 (24–31); setae e 4 (3–5) on ventral annulus 46 (39–53); setae f 16 (11–20) on 5th–7th ventral annulus from rear. Setae h1 0.5–1, h2 32 (30–48). In three females distinct outlines of previously described anal secretory apparatus (Chetverikov et al. 2023b) were observed under telosomal cuticle (Figure 6I).

Male (n=3; Figures 6 H, 7 C, D)

Body — Fusiform, 123–142, 45–51 wide, light orange.

Gnathosoma — 15–19, projecting down and slightly forward, pedipalp coxal seta (ep) 2–4, dorsal pedipalp genual seta (d) angled consisting of basic and accessory branches, 7–8, cheliceral stylets 10–16.

Prodorsal shield — 41–49, including length of frontal lobe 6–7, 42–49 wide, design similar to that of female. Scapular tubercles ahead of rear shield margin, 11–12 apart, scapular setae (sc) 2–3, directed toward each other.

Coxigenital region — With 11–13 semiannuli between coxae and genitalia. Coxal plates with short lines and microtubercles, anterolateral setae on coxisternum І (1b) 4–6, 8–11 apart, proximal setae on coxisternum І (1a) 11–14, 5–7 apart, proximal setae on coxisternum ІІ (2a) 20–25, 16–20 apart. Prosternal apodeme 10–12.

Leg I — 23–26, femur 8–10, with weak subcircular ridge, basiventral femoral seta (bv) absent; genu 4–6, antaxial genual setae (l″) 16–20; tibia 5–6, paraxial tibial setae (l′) 3; tarsus 4–5, paraxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft′) 8–10, antaxial fastigial tarsal setae (ft″) 10–12, paraxial unguinal tarsal setae (u′) 1–2, angled; tarsal empodium (em) 3–5, simple, 3-rayed; tarsal solenidion (ω) 3–4, knobbed.

Leg ІІ — 22–25, femur 6–8, with weak subcircular ridge, basiventral femoral setae (bv) absent; genu 3–4, antaxial genual setae (l″) 3–5; tibia 4–5; tarsus 4–5, paraxial, fastigial, tarsal setae (ft′) 2–3, antaxial, fastigial, tarsal setae (ft″) 12–14, paraxial unguinal tarsal setae (u′) 1–2, angled; tarsal empodium (em) 3–4, simple, 3-rayed, tarsal solenidion (ω) 3–5, knobbed.

Genital area — 14–18, 11–14 wide, eu very short, 3a 15–19, 10–12 apart, genital cuticle flanked by tubercles of 3a microtuberculate.

Opisthosoma — Dorsally with 40–43 annuli, with microtuberculate median longitudinal ridge fading above setae f; ventrally with microtuberculate 62–65 annuli. Setae c2 3–5 on ventral annulus 13–20; setae d 10–13 on ventral annulus 24–33; setae e 3 on ventral annulus 34–48; setae f 15–16 on 6th ventral semiannulus from rear. Setae h1 0.5–1, h2 30–38.

Host plant

Host plant — Carex pediformis Mey, 1831 (Poales: Cyperaceae).

Relation to the host — Mites live on upper leaf surface in medial furrow of the leaflet causing no visible damage.

Type locality and material

Type locality — Russia: Buryatia, Ulan-Ude city, 51°49′02.0″N 107°44′10.0″E.

Type material — Holotype female on slide #E1675, paratypes on slide #E1676, collected on 21 June 2011 at the type locality, coll. P. Chetverikov. Type material deposited in Acarological Collection of ZIN RAS.

Etymology

The species epithet ulanudensis is an adjective, gender feminine, derived from the name of the city Ulan-Ude where the new species was found.

Differential diagnosis

Including the new species, the genus Leipothrix contains eleven members associated with monocots (Figure 1). Although a proper phylogenetic analysis is currently precluded by the unavailability of type specimens and poor molecular data, a comparison of the original descriptions unexpectedly reveals that the new species is more closely aligned with the fern-associated species L. osmundastris n. sp. and L. pterisfoliae than to any of the other monocot-associated species, due to similarities in the prodorsal shield design and pattern of dorsal opisthosomal microtuberculation. The main differences between L. ulanudensis n. sp., L. osmundastris n. sp. and L. pterisfoliae concern ornamentation of distal part of genital coverflap, presence/absence of cell-like network on prodorsal shield, number of opisthosomal annuli and empodial rays, and lengths of setae sc and d (Table 2).

Discussion

Towards resolving the phylogeny of Leipothrix

In this article, we describe two new species of the genus Leipothrix from the USA and Russia. Both species represent the first records of this mite genus on ferns in vast regions of North America (L. osmundastris n. sp.) and on monocots in Siberia (L. ulanudensis n. sp.). While compiling differential diagnoses for these species, we noted their pronounced morphological similarity to L. pterisfolii Lotfollahi & de Lillo 2017, a species described from ferns Polypodium vulgare L. (Polypodiaceae) and Gymnocarpium dryopteris (L.) Newman (Cystopteridaceae) in Iran. The morphological resemblance among these three Leipothrix species may suggest their common ancestry. However, this hypothesis is difficult to reconcile with the considerable geographic separation of their collection sites and the phylogenetic distance between their hosts (monocots and ferns). Interestingly, similar cases are already known in Eriophyoidea. For instance, the recently described species Nothopoda todeica Chetverikov et al. 2023, found on the endemic relict fern Todea barbara (L.) T. Moore (Osmundaceae) in South Africa, closely resembles N. camelliae Lv et al. 2022 infesting the eudicot host Camellia oleifera Abel (Theaceae) in Asia (Chetverikov 2023c). These examples suggest that multiple host shifts likely occurred during the evolution of the genus Leipothrix. The plant phylogeny follows a simplified topology: (ferns, ((magnoliids, monocots), eudicots)) (Zuntini et al. 2025). Whether Leipothrix evolution aligns with this pattern, and if its species groups associated with major vascular plant clades (Figure 1) are monophyletic, remains unknown. Future comprehensive analyses could clarify this, though it will require extensive international collaboration and material collection across multiple countries.

CLSM for investigating old slide-mounted specimens of Eriophyoidea

Both new Leipothrix species were described from relatively old material collected more than ten years ago. Different mounting media were used for slide preparation: modified Berlese medium with iodine (Amrine & Manson 1996) for L. osmundastris n. sp. and classic Hoyer's medium without iodine (Upton 1993) for L. ulanudensis n. sp. The mites mounted in Hoyer's medium were difficult to examine due to severe fading. To clarify topography of the mite exoskeleton, we employed confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). This method allowed us to obtain clearer images of the ornamentation of the prodorsal shield (a key diagnostic feature in eriophyoid mites), confirm the presence of ventral femoral ridges, and capture high-quality images of the opisthosomal annuli (Figure 7). A similar issue was previously resolved using CLSM when studying old slide-mounted specimens of Oziella mites (Chetverikov 2016a). Thus, CLSM can be recommended for examining old eriophyoid mite specimens when conventional light microscopy yields suboptimal results.

Serial spermatophores or male-specific endobionts?

While describing males of L. osmundastris n. sp., we observed serial structures within some of the male bodies, each consisting of a subspherical pad connected via a thin filamentous stalk to a larger spheroid (Figure 4G). These structures could be interpreted as previously unreported male-specific symbionts or parasite eggs. Alternatively, their morphology closely resembles that of typical eriophyoid spermatophores, which are comprised of a sperm capsule, stalk, and pad-like base (Sternlicht, Griffiths 1974). Their dimensions also correspond precisely to the topography of the male external genitalia and the cuticular genital chamber typically observed in male Eriophyoidea (Chetverikov 2015). These structures were found in only 3 (50%) of 6 males of L. osmundastris n. sp. from the type series collected in August 2012. In August 2025 the second author revisited the type locality and recollected specimens. Despite the presence of numerous males, none contained similar internal structures. This sporadic occurrence suggests a potential link to male senescence. Navia et al. (2005) reported ovoviviparity in senescent females of Aceria guerreronis Keifer, 1965 that become unable to lay eggs, resulting in larvae emerging internally. By analogy, our observation of putative serial spermatophores may represent a similar phenomenon in aged males that are unable to successfully deposit their spermatophores, leading to an internal accumulation.

It is also possible that serial spermatophores are a specific trait of the normal reproductive biology of the Leipothrix males. If this is true, our finding is particularly intriguing because, previous studies suggest that in Eriophyoidea spermatophores form one at a time within the genital chamber and are extruded through genital channel using a unique muscular spermatophore pump (Alberti, Coons 1999; Nuzzaci & Alberti, 1996; Chetverikov, 2015). Presence of a series of putative fully formed spermatophores within a male of L. osmundastris n. sp. suggests a different mechanism of spermatophore formation and possibly novel structural adaptations of male internal genitalia. Notably, Leipothrix males are usually half the size of females and exhibit significantly faster movement (Chetverikov et al. 2023a). According to rare descriptions of Leipothrix males in the literature (e.g., Lotfollahi & de Lillo 2017), they have typical external genitalia, but no data on their genital anatomy is available. Further studies on the male reproductive system of Leipothrix are needed to clarify their spermatophore production mechanism and determine whether it differs from that of other Eriophyoidea.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation, grant № 25-14-00118 to the first author.

References

- Alberti G. & Coons L.B. 1999. Acari - Mites. In: Harrison F.W. (ed.) Microscopic Anatomy of Invertebrates. Vol. 8c. New York, Wiley-Liss: 515-1265

- Amrine J.W.Jr. & Manson D.C.M. 1996. Chapter 1.6.3 Preparation, mounting and descriptive study of eriophyoid mites. In: Lindquist E.E., Sabelis M. W. & Bruin J. (Eds). Eriophyoid Mites: Their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control. World Crop Pests, vol. 6. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishing. pp. 383-396. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1572-4379(96)80023-6

- Amrine J.W.Jr., Stasny T.A.H. & Flechtmann C.H.W. 2003. Revised keys to the world genera of the Eriophyoidea (Acari: Prostigmata). Michigan: Indira Publishing House. pp. 244

- Bolton S.J., Chetverikov P.E. & Klompen H. 2017. Morphological support for a clade comprising two vermiform mite lineages: Eriophyoidea (Acariformes) and Nematalycidae (Acariformes). Syst. Appl. Acarol., 22(8): 1096-1131. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.22.8.2

- Bolton S.J., Chetverikov P.E., Ochoa R. & Klimov P.B. 2023. Where Eriophyoidea (Acariformes) belong in the tree of life. Insects, 14(6): 527. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14060527

- Chetverikov P.E. 2005. Eriophyid mites (Acari, Eriophyoidea: Eriophyidae) of the genus Leipothrix Keifer, 1966 from sedges (Cyperaceae). Acarina, 13(2): 145-15

- Chetverikov P.E. 2014. Comparative confocal microscopy of internal genitalia of phytoptine mites (Eriophyoidea, Phytoptidae): new generic diagnoses reflecting host-plant associations. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 62(2): 129-160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-013-9734-2

- Chetverikov P.E. 2015. Confocal microscopy reveals uniform male reproductive anatomy in eriophyoid mites (Acariformes, Eriophyoidea) including spermatophore pump and paired vasa deferentia. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 66(4): 555-574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-015-9924-1

- Chetverikov P.E. 2016a. New species and records of phytoptid mites (Acari: Eriophyoidea: Phytoptidae) on sedges (Cyperaceae) from the Russian Far East. Zootaxa, 4061(4): 367-380. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4061.4.3

- Chetverikov P.E. 2016b. Video projector: a digital replacement for camera lucida for drawing mites and other microscopic objects. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 21(9): 1278-1280.

- Chetverikov P.E., Craemer C., Cvrković T., Klimov P.B., Petanović R.U., Romanovich A.E., Sukhareva S.I., Zukoff S., Bolton S. & Amrine J. 2021. Molecular phylogeny of the phytoparasitic mite family Phytoptidae (Acariformes: Eriophyoidea) identified the female genitalic anatomy as a major macroevolutionary factor and revealed multiple origins of gall induction. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 83: 31-68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-020-00571-6

- Chetverikov P.E., Bolton S.J., Craemer C., Gankevich V.D. & Zhuk A.S. 2023a. Atypically Shaped Setae in Gall Mites (Acariformes, Eriophyoidea) and Mitogenomics of the Genus Leipothrix Keifer (Eriophyidae). Insects, 14(9): 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14090759

- Chetverikov P.E., Craemer C., Gankevich V.D., Vishnyakov A.E. & Zhuk A.S. 2023b. A new webbing Aberoptus species from South Africa provides insight in silk production in gall mites (Eriophyoidea). Diversity, 15(2): 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15020151

- Chetverikov P.E., Craemer C., Gankevich V.D. & Zhuk A.S. 2023c. Integrative taxonomy of the gall mite Nothopoda todeica n. sp. (Eriophyidae) from the disjunct Afro-Australasian fern Todea barbara: morphology, phylogeny, and mitogenomics. Insects, 14(6): 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14060507

- Craemer C. 2010. A systematic appraisal of the Eriophyoidea (Acari: Prostigmata) [PhD Thesis]. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/28832?show=full

- Gankevich V.D. & Chetverikov P.E. 2025. Mitogenomic evidence for the monophyly of blackcurrant gall mite subfamily Cecidophyinae (Eriophyoidea, Eriophyidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol., 95(1): 9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-025-01027-5

- Greenhalgh R., Dermauw W., Glas J.J., Rombauts S., Wybouw N., Thomas J., Alba J.M., Prithham E.J., Legarrea S., Feyereisen R., Peer V.Y., Leeuwen T.V., Clark R.M. & Kant M.R. 2020. Genome streamlining in a minute herbivore that manipulates its host plant. Elife, 9: e56689. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.56689

- Han X., Xie A.-C. & Chen R.-Z. 2025. Three new eriophyoid mites (Eriophyidae: Leipothrix) from Jilin Province, China. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 30(1): 196-210. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.30.1.14

- Hao K.-X., Lotfollahi P. & Xue X.-F. 2023. Three New Eriophyid Mite Species from China (Acari: Eriophyidae). Insects, 14(2): 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14020159

- Jǒcić I. & Petanović R. 2012. Checklist of the Eriophyoid mite fauna of Montenegro (Acari: Prostigmata: Eriophyoidea). Acta Entomol. Serb., 17(1/2): 141-166

- Klimov P.B., Chetverikov P.E., Dodueva I.E., Vishnyakov A.E., Bolton S.J., Paponova S.S., Lutova L.A. & Tolstikov A.V. 2022. Symbiotic bacteria of the gall-inducing mite Fragariocoptes setiger (Eriophyoidea) and phylogenomic resolution of the eriophyoid position among Acari. Sci. Rep., 12: 3811. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07535-3

- Klimov P.B., Kolesnikov V.B., Vorontsov D.D., Ball A.D., Bolton S.J., Mellish C., Edgecombe G.D., Pepato A.R., Chetverikov P.E., He Q., Perotti M.A. & Braig H.R. 2025. The evolutionary history and timeline of mites in ancient soils. Sci. Rep., 15(1): 13555. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96115-2

- Li H.-S., Xue X.-F. & Hong X.-Y. 2014. Homoplastic evolution and host association of Eriophyoidea (Acari, Prostigmata) conflict with the morphological-based taxonomic system. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol., 78: 185-198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2014.05.014

- Lindquist E.E. 1996. Chapter 1.1 External anatomy and systematics 1.1.1. External anatomy and notation of structures. In: Lindquist E.E., Sabelis M.W. & Bruin J. (Eds). Eriophyoid mites: their biology, natural enemies and control. World Crop Pests 6. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 3-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1572-4379(96)80003-0

- Lotfollahi P. & de Lillo E. 2017. Eriophyoid mites from ferns: description of a new Leipothrix Keifer species (Eriophyidae: Phyllocoptinae) from the Arasbaran forests (Iran) and a key to the world species. Acarologia, 57(4): 731-745. https://doi.org/10.24349/acarologia/20174179

- Navia D., Flechtmann C. H., & Amrine Jr, J. W. 2005. Supposed ovoviviparity and viviparity in the coconut mite, Aceria guerreronis Keifer (Prostigmata: Eriophyidae), as a result of female senility. Int. J. Acarol., 31(1): 63-65. https://doi.org/10.1080/01647950508684418

- Nuzzaci G. & Alberti G. 1996. Internal anatomy and physiology. In: Lindquist E.E., Sabelis M.W. & Bruin J. (Eds). Eriophyoid Mites: Their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control. World Crop Pests, vol. 6. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishing. pp. 101-150 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1572-4379(96)80006-6

- Pińkowska A. & Lewandowski M. 2024. Reassignment of Epitrimerus violarius Liro, 1941 (Acariformes: Eriophyoidea) to the genus Leipothrix, with a supplementary description of the species. Int. J. Acarol., 50(3): 300-305. https://doi.org/10.1080/01647954.2024.2318359

- Ripka G. & Kiss B. 2020. A new Leipothrix species from Hungary. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 25(5): 891-901. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.25.5.12

- Schmidt A.R., Jancke S., Lindquist E.E., Ragazzi E., Roghi G., Nascimbene P.C., Schmidt K., Wappler T. & Grimaldi D.A. 2012. Arthropods in amber from the Triassic Period. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 109(37): 14796-14801. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1208464109

- Shao Z.K., Chen L., Sun J.T. & Xue X.F. 2025. A chromosome-level genome assembly of eriophyoid mite Setoptus koraiensis. Sci. Data, 12(1): 446. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04814-2

- Sidorchuk E.A., Schmidt A.R., Ragazzi E., Roghi G. & Lindquist E.E. 2014. Plant-feeding mite diversity in Triassic amber (Acari: Tetrapodili). J. Syst. Palaeontol., 13: 129-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2013.867373

- Sternlicht, M., Griffiths D.A. 1974. The emission and form of spermatophores and the fine structure of adult Eriophyes sheldoni Ewing (Acarina, Eriophyoidea). Bull. Ent. Res., 63(4): 561-565. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485300047799

- Sukhareva S.I. 1994. Family Phytoptidae Murray 1877 (Acari: Tetrapodili), its composition, structure and suggested ways of evolution. Acarina, 2(1): 47-72

- Tan Y.-C., Kontschán J. & Wang G.-Q. 2016. Two new Leipothrix species from ferns in Yunnan Province (Acari: Eriophyidae). Syst. Appl. Acarol., 21(11): 1501-1512. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.21.11.5

- Upton M.S. 1993. Aqueous gum-chloral slide mounting media: an historical review. Bull. Entomol. Res., 83(2): 267-274. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485300034763

- Varandi F.R., Irani-Nejad K.H. & Lotfollahi P. 2020. Two new eriophyid species (Acariformes: Eriophyidae) from North of Iran. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 25(7): 1178-1187. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.25.7.2

- Wang F., Han X. & Hong X.-Y. 2017. Two new Leipothrix species from medicinal plants in China. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 22(8): 1217-1229. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.22.8.8

- Xiao H., Xie A.-C. & Chen R.-Z. 2025. Three new eriophyoid mites from Jilin Province, China. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 30(1): 196-210. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.30.1.14

- Xue X.-F., Dong Y., Deng W., Hong X.-Y. & Shao R. 2017. The phylogenetic position of eriophyoid mites (superfamily Eriophyoidea) in Acariformes inferred from the sequences of mitochondrial genomes and nuclear small subunit (18S) rRNA gene. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol., 109: 271-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2017.01.009

- Yao L.F., Huang Y.H. & Xue X.F. 2024. Five new Glossilus mites from China (Acari: Eriophyoidea). Syst. Appl. Acarol., 29(5): 579-599. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.29.5.4

- Zhang Q., Lu Y.-W., Liu X.-Y., Li Y., Gao W.-N., Sun J.-T., Hong X.-Y., Shao R. & Xue X.-F. 2024. Phylogenomics resolves the higher-level phylogeny of herbivorous eriophyoid mites (Acariformes: Eriophyoidea). BMC Biol., 22: 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-024-01870-9

- Zuntini A.R., Carruthers T., Maurin O., Bailey P.C., Leempoel K., Brewer G.E. & Knapp S. 2024. Phylogenomics and the rise of the angiosperms. Nature, 629(8013): 843-850. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07324-0

2025-08-30

Date accepted:

2025-11-26

Date published:

2025-12-08

Edited by:

Navia, Denise

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

2025 Chetverikov, Philipp E.; Kudryavtzev, Andrey T. and Amrine, James W.

Download the citation

RIS with abstract

(Zotero, Endnote, Reference Manager, ProCite, RefWorks, Mendeley)

RIS without abstract

BIB

(Zotero, BibTeX)

TXT

(PubMed, Txt)