Structural and elemental characterization of α-chitin isolated from Eupelops torulosus torulosus and Achipteria (A.) acuta (Acari, Oribatida), in related to soil geochemistry

Per, Sedat  1

1

1✉ Department of Chemistry and Chemical Processing Technology, Mustafa Çıkrıkçıoğlu Vocational School, Kayseri University, Kayseri, Türkiye.

2025 - Volume: 65 Issue: 4 pages: 1124-1135

https://doi.org/10.24349/0n51-bzmdOriginal research

Keywords

Abstract

Introduction

Oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) are tiny arthropods that are common in almost all terrestrial ecosystems of the world. They have an important role in maintaining the physicochemical dynamics of the soil and actively participate in the decomposition process of organic residues in the soil. They comprise about 11,332 identified species that belong to 1306 genera and 162 families (Subías 2004; Moitra 2013; Wissuwa et al. 2013; Arillo et al. 2022; Cordes et al. 2022).

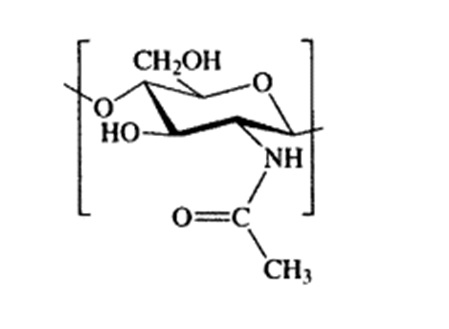

The carbohydrate used by arthropods to form the exoskeleton and forming the cell wall of fungi is called chitin. Chitin, with its chemical name poly β-(1→4)-N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, is a very important natural polysaccharide that was first identified in the 1800s (Braconnot 1811). It shows a long chain structure formed by the repetition of two N-acetylglucosamine units linked by beta 1,4 bonds (Chitin et al. 1973).The most important feature of chitin is that it is synthesized by many living organisms and when the annual amount of chitin produced in the world is examined, it is the most abundant polymer after cellulose.

All research on chitin has shown that it is non-toxic and biodegradable. These properties make chitin and its derivatives usable in many important application areas in a wide area, some of these areas are agriculture, medicine, food industry, textile and cosmetics (Jeon et al. 2022; Rinaudo 2006; Krantz and Walter, 2009; Anitha et al. 2014).

It is known from literature research and studies so far that chitin has multiple functional properties. Chitin is insoluble in any solvent containing organic or mineral acids, such as water. These solubility problems may limit their use in physiological functional foods. However, chitin oligomers are not only water-soluble, and their solutions have low viscosity values, but they can also be absorbed in the human gut. They can have a great deal of physiological functionality in in vivo systems (Bough 1976; No et al. 1989; Knorr 1991; Arvanitoyannis et al. 1998).

In this study, chitin extraction of two different mite species, Eupelops torulosus torulosus and Achipteria (A.) acuta was carried out. The resulting chitins were observed by light microscopy and characterized by FT-IR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy) and SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy) analysis. Our findings show that chitin, which is obtained in high purity and constitutes a large portion of the organism's body structure, is the second most abundant natural polymer in the world; in this study, its characterization was completed using the latest available technologies.

Additionally, ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry) analysis was performed to determine the elemental composition of both the extracted chitin and the soil samples, offering insights into trace element content and potential bioaccumulation in the chitin matrix. This dual analysis was conducted not only to assess the purity and potential functional modifications of chitin due to metal incorporation but also to investigate the correlation between environmental elemental availability in soil and its biological accumulation in oribatid mites. Since oribatid mites are in constant contact with the soil environment and feed on decomposing organic material, they may reflect the geochemical characteristics of their habitats. Identifying the trace metal profile in both the mites and their surrounding matrix provides critical ecological information on bioavailability, trophic transfer, and possible adaptive strategies related to elemental uptake. Moreover, the presence of certain trace elements within the chitin matrix may influence its physicochemical and biological properties, potentially affecting its suitability for specific biomedical or industrial applications.

Materials and methods

Oribatid mites sampling and locations

Specimens of Eupelops torulosus torulosus and Achipteria (A.) acuta were collected from Soğuksu National Park (Ankara-Turkey) using Berlese funnels. The collecting data of E. torulosus torulosus is: 40°28.018′N, 032°37.846′E, 1095 m, soil, 20 April 2019, 70 exs. The collecting data of A. (A.) acuta specimens is: 40°27.174′N, 032°37.258′E, 1167 m, soil under Pinus sp., 03 June 2018, 70 exs.

Chitin Extraction

Chitin extraction consisted of 3 basic steps, the first was mineral separation, the second protein separation and the third the separation of acetyl groups. The mineral separation step was completely carried out within 15 minutes in 0.25 M 50 mL HCl medium at room temperature. Before starting the protein separation process, the samples were washed 3 times with distilled water, and immediately after that, they were kept in 1 M 50 mL NaOH at 70 °C for 24 hours. Finally, the process was completed by keeping the acetyl groups in a 1:1 mixture of HCl and NaOH at 80 °C for 48 hours.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

To observe the bonds in the chitin and the differences in bonding, analysis was performed with a Bruker Spectrometer (Alpha Platinum, ATR), in the region of 400-4000 cm-1. The resolution was 2 cm-1 in the analyses. All FT-IR analyses were taken at the Erciyes University Technology Research and Application Center.

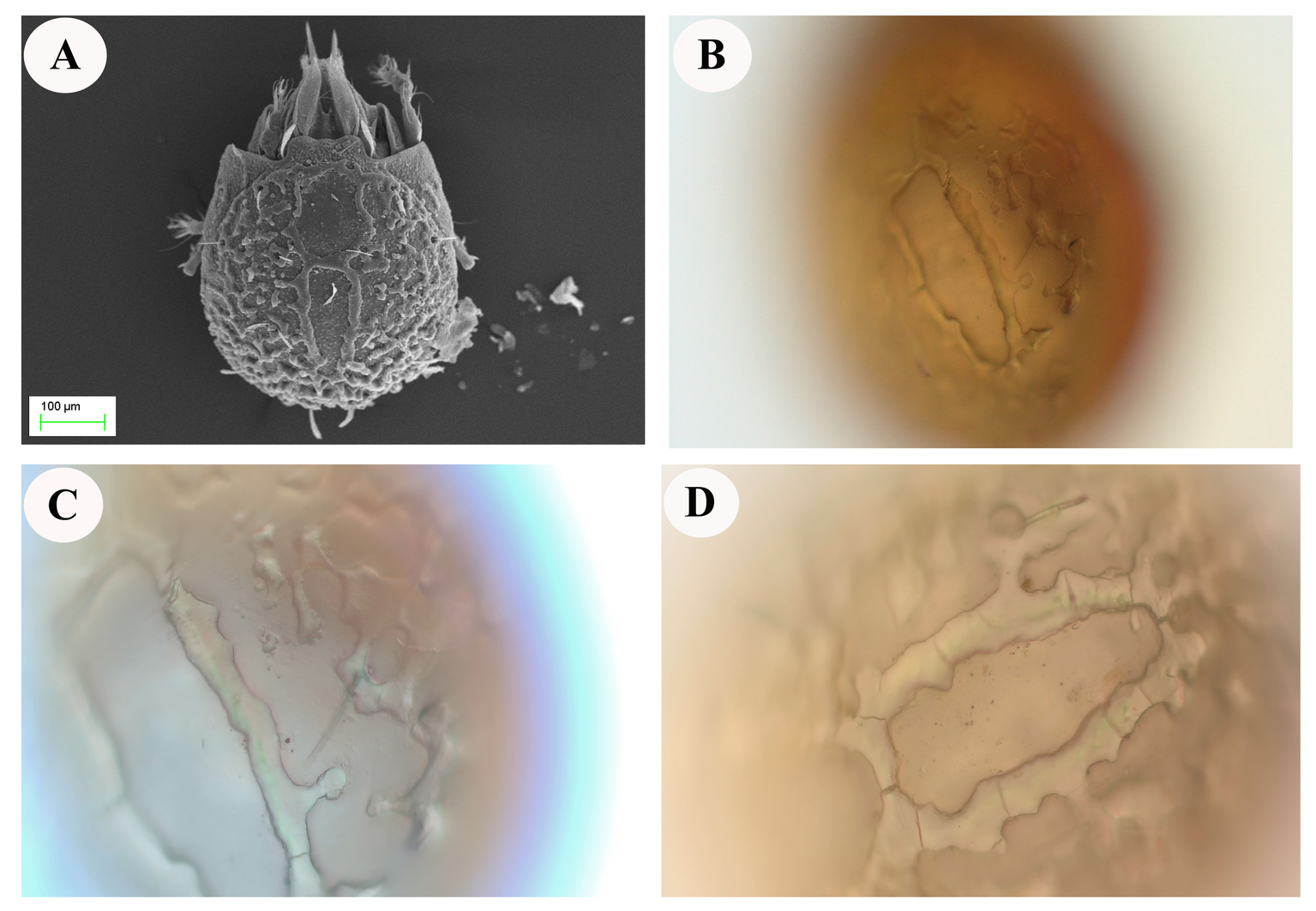

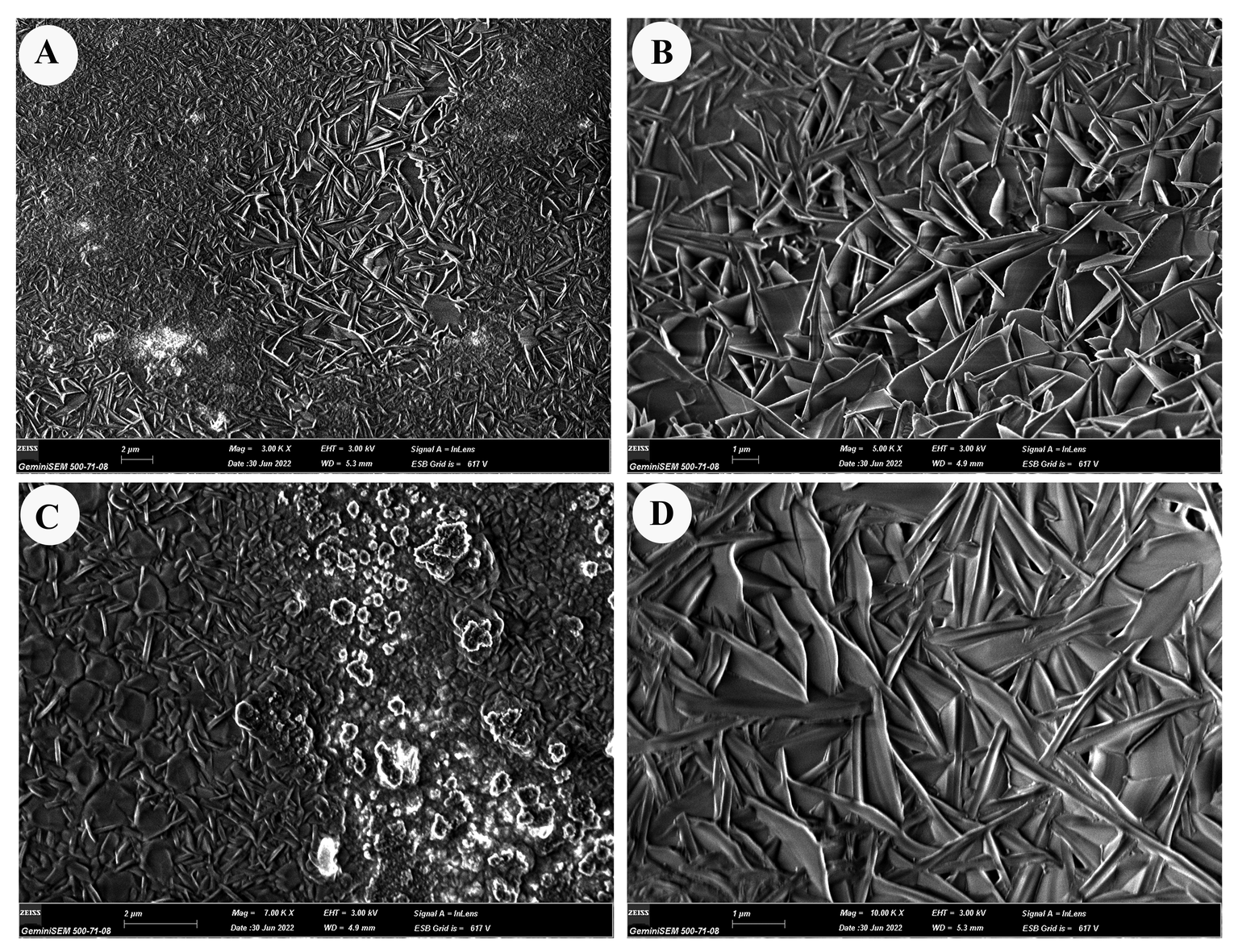

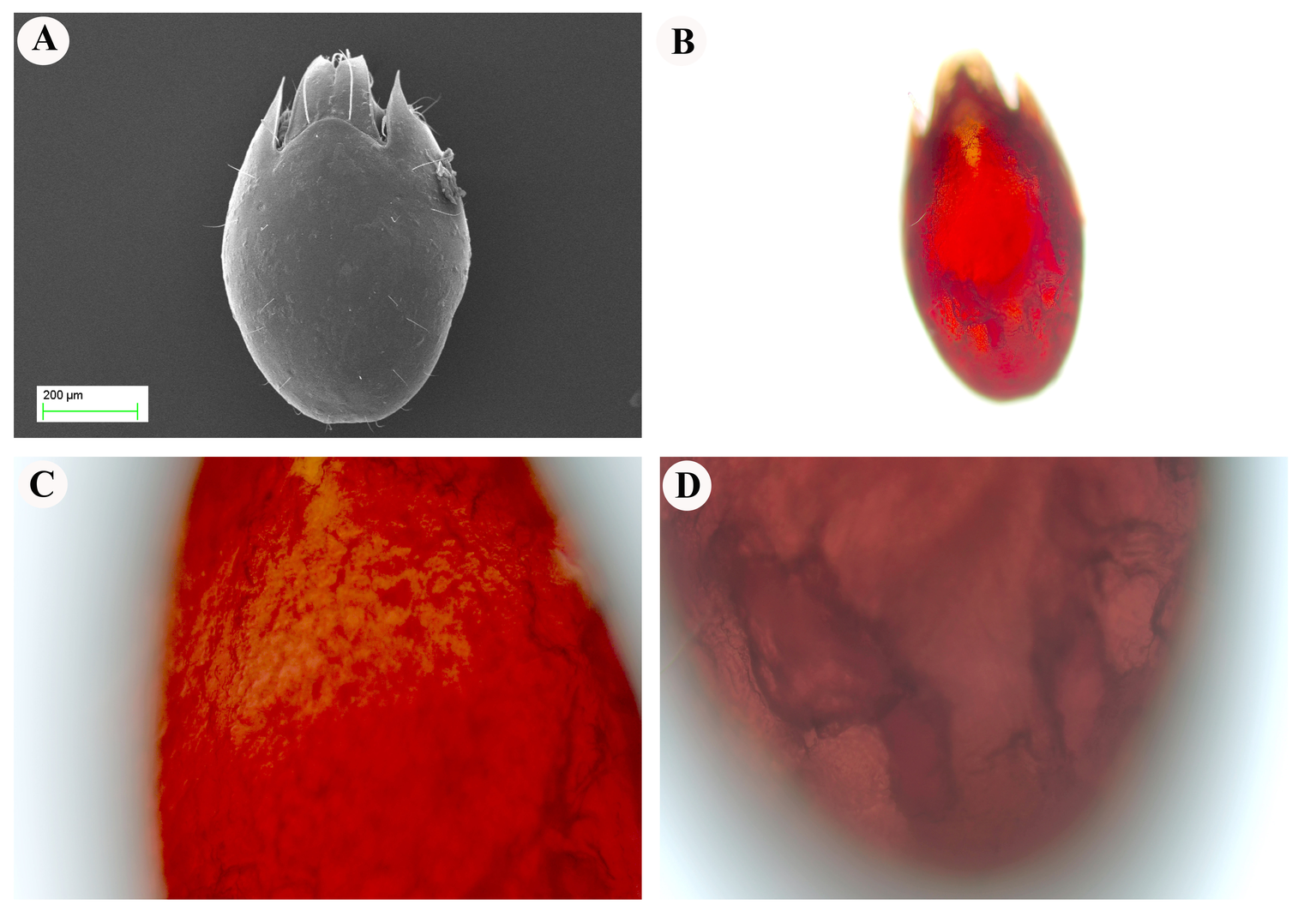

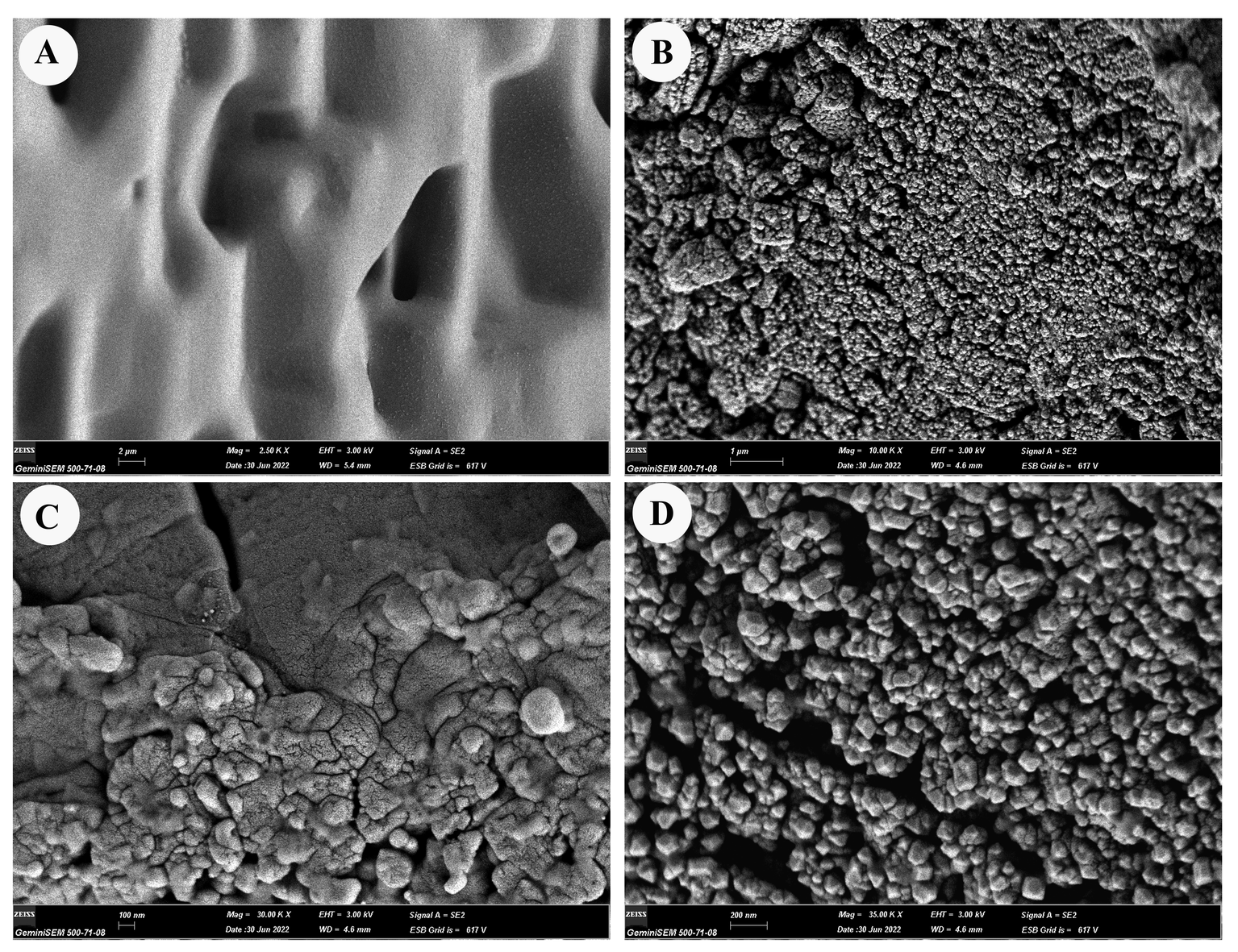

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Light microscopy image

Scanning electron microscope was used to examine the surface of E. torulosus torulosus and A. (A.) acuta samples (Figure 5A and 7A). After the extracted and dried samples were placed in an aluminum holder, Au-Pd was coated (to ensure conductivity) and examined at the Erciyes University Nanotechnology Research and Application Center. The same structures were observed and photographed under a ZEISS Axiolab 5 trinocular microscope with Axio Imager software (ZEISS, Jena, Germany), (Figure 5B-D and 7B-D).

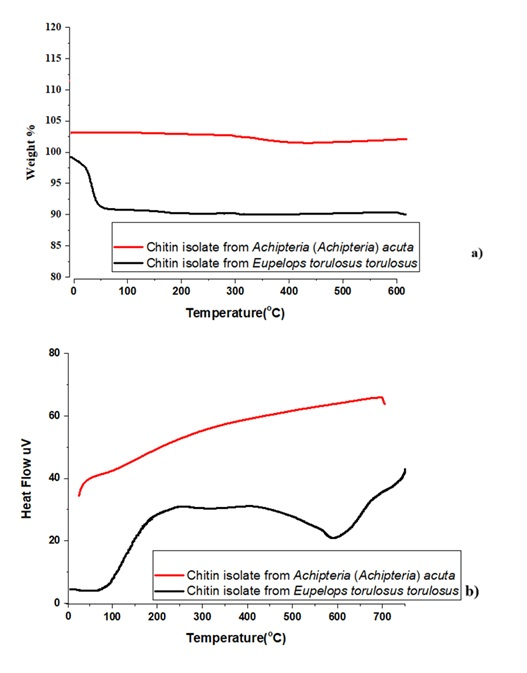

TGA Analysis

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) is a technique used to study the thermal decomposition of materials as a function of temperature. When it comes to chitin, TGA can be employed to investigate its thermal stability and decomposition behavior. The TGA curve typically shows the weight loss of the sample as it is heated. Thermogravimetry (TG) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) measurements were conducted by the PerkinElmer (Diamond) high-temperature thermal analyzer with 5–20 mg samples and a heating rate of 10 °C/min from 50 to 600 °C in air.

ICP Analysıs

ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry) analysis was performed using an Agilent 7500a ICP-MS system equipped with an autosampler and a Babington nebulizer to ensure efficient sample introduction. The instrument utilized nickel cones, a quartz sputtering chamber, a standard torch, and a peristaltic pump, contributing to the sensitivity and accuracy of measurements. High-purity argon gas was used to generate the plasma for ionization. Calibration was performed daily with a multi-element standard solution to ensure reliable quantification, and all samples were analyzed in triplicate for reproducibility (Table 1).

Download as

Parameters

Value

Radio frequency power [W]

1280 W

Sample depth

7.9 mm

Torch-H

-0.4 mm

Torch-V

1 mm

Carrier gas

1.23 L/min

Makeup gas

0.1 L/min

Auxiliary gas flow rate

0.9 L/min

Plasma gas flow rate

15 L/min

Nebulizer pump

0.12 rps

Spray chamber temperature

2 °C

The analysis employed a full quantitative mode with internal standards (45Sc, 103Rh, and 209Bi) to correct for potential matrix effects and plasma fluctuations. Calibration curves for trace elements—including Al, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, As, Se, Sr, Cd, Sn, Hg, and Pb—were prepared over a concentration range of 0–50 µg L⁻¹, all showing excellent linearity (R² > 0.99).

Download as

Element

Certified value (%)

Found concentration (μg g⁻¹)

Recovery (%)

Calcium (Ca)

1.2 ± 0.1

1.18 ± 0.05

98.3

Magnesium (Mg)

0.35 ± 0.02

0.34 ± 0.01

97.1

Iron (Fe)

0.45 ± 0.03

0.44 ± 0.02

97.8

Zinc (Zn)

0.15 ± 0.01

0.14 ± 0.01

93.3

To verify method accuracy, the certified reference material NIST SRM 2709 San Joaquin Soil was analyzed using the same protocol, confirming the reliability of the results. Detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) limits were calculated based on blank measurements to assess sensitivity, with values detailed in Table 2.

Overall, this rigorous ICP-MS approach allowed precise and reliable determination of trace elements in both the extracted chitin and soil samples (Table 3).

Download as

Element

Concentration in oribatid mite tissues (μg g⁻¹)

Concentration in corresponding soil microhabitats (μg g⁻¹)

Recovery (%)

Calcium (Ca)

1250 ± 45

1180 ± 38

95.2

Magnesium (Mg)

380 ± 12

365 ± 15

96.1

Iron (Fe)

460 ± 20

445 ± 18

96.7

Zinc (Zn)

150 ± 8

142 ± 7

94.7

Results

FTIR Analysis

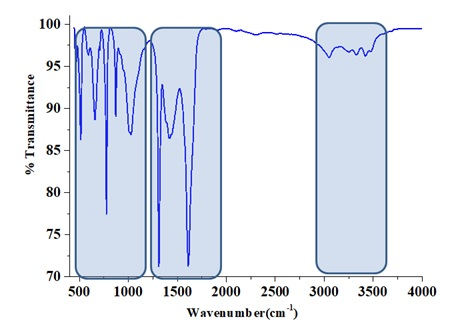

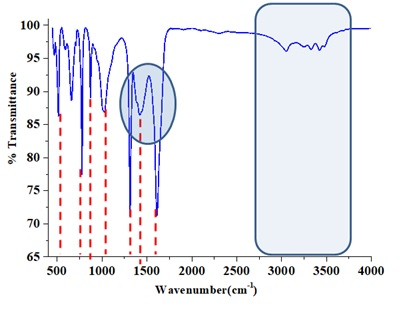

The FTIR spectra of chitin layers successfully isolated from Eupelops torulosus torulosus (Koch, 1839) and Achipteria (A.) acuta Berlese, 1908 (Figures 1 and 2) exhibited characteristic absorption bands around 1650 cm⁻¹ and 1550 cm⁻¹, corresponding to the amide I (C=O stretching) and amide II (N-H bending and C-N stretching) bands, respectively. These confirm the presence of chitin's secondary amide groups. Additional key FTIR bands observed include; 3430–3420 cm⁻¹ (O–H stretching), 3100–3090 cm⁻¹ (symmetric N–H stretching), 1380–1370 cm⁻¹ (C–H bending), 1150–1160 cm⁻¹ (C–O–C symmetric stretching). When compared with literature data, the spectra confirm that both samples exhibit the α-chitin from (Kılcı et al. 2024). The interpretation of bonding structures was supported by the data in Table 4, while Figure 3 illustrates the molecular structure of chitin.

Download as

Functional groups and vibration modes

Chitin obtained from Eupelops torulosus torulosus

Chitin obtained from Achipteria (Achipteria) acuta

Commercial α chitin

N-H streching

3100

3090

3104-3260

CH3 sym. stretch and CH~2 ~asym. stretch

2950

2950

2940

CH~3 ~sym. stretch

2875

2870

2875

C=O secondary amide stretch

1650

1645

1650

1620

N-H bend C-N strech

1625

1620

1550

CH bend, CH3 sym. deformation

1380

1380

1370

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA/DTA)

Thermogravimetric analysis (Figure 4) revealed a gradual weight loss up to approximately 100 °C, attributed to the evaporation of surface-bound water. A more substantial weight loss was observed between 100 °C and 200 °C, representing the primary thermal decomposition of chitin.

The DTA curve showed an endothermic peak between 200 °C and 300 °C, indicating structural decomposition processes such as bond breaking and volatilization. Occasional exothermic peaks were also recorded, likely related to secondary reactions or crystallization of impurities.

Microscopic Observations

Reticulated structures on the surfaces of E. torulosus torulosus and A. (A.) acuta are seen under a light microscope before chitin extraction (mineral separation, protein separation, and acetyl group removal) (Figure 5B-D and 7B-D). SEM imaging provided detailed insight into the surface morphology. In E. torulosus torulosus, the chitin layer was well-isolated and displayed a clear fibrillary structure (Figure 6), indicative of long polysaccharide chains typical of chitin. In A. (A.) acuta, the chitin layer varied from smooth to granular at different magnifications, depending on factors such as surface texture, layer thickness, sample preparation and possible impurities (Figure 8).

Elemental Analysis (ICP-MS)

ICP-MS analysis confirmed the presence and quantified the levels of essential elements calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), iron (Fe), and zinc (Zn) in both the tissues of oribatid mite species and their corresponding soil microhabitats (Tables 3 and 4). The consistent detection of these elements across biological and environmental matrices underscores their ecological and physiological significance. The measured concentrations were in agreement with values reported in previous ecological and environmental studies, supporting the accuracy, reliability, and sensitivity of the inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) method employed. While iron and zinc were detected at relatively lower levels compared to calcium and magnesium, their concentrations are nonetheless ecologically relevant due to their essential roles in numerous biochemical processes. Collectively, these results highlight the potential of oribatid mites as effective bioindicators for assessing soil geochemistry and ecosystem health.

Discussion

The FTIR results confirmed the successful isolation of chitin from E. torulosus torulosus and A. (A.) acuta, with characteristic amide I and II peaks supporting the presence of α-chitin. The distinct and sharper peaks observed in A. (A.) acuta may be attributed to a thinner or more refined chitin layer or more effective extraction.

Thermal analysis (TGA/DTA) supported the structural integrity and thermal stability of the isolated chitin. The initial mass loss due to moisture evaporation was followed by a significant degradation phase between 100–200 °C, consistent with known chitin decomposition behavior. The DTA endothermic peak within the 200–300 °C range further verified structural degradation, while occasional exothermic peaks pointed to secondary physical or chemical processes.

Microscopic (SEM and light microscopy) analyses revealed that the fibrous, fibrillar structure characteristic of chitin was preserved in the isolated layers. The chitin layer in E. torulosus torulosus showed clearer, more defined fibrils, possibly due to more effective separation. Differences in surface texture between species could be attributed to natural structural variation, sample preparation, or environmental factors.

Elemental analysis provided critical insights into the metal-binding properties of the chitin structure. The presence of Ca and Mg suggests a structural role, possibly through ionic cross-linking within the chitin matrix, enhancing rigidity and stability. Fe and Zn, though present in lower amounts, are essential in various enzymatic and redox processes. Their presence likely reflects both environmental availability and physiological incorporation into the exoskeleton.

Interspecific and site-specific differences in elemental concentrations suggest adaptive responses to local microhabitat conditions. These findings align with previous studies indicating that oribatid mites can selectively accumulate elements based on environmental availability, making them potential bioindicators of soil health (e.g., Behan-Pelletier, 1999; Zuzana et al. 2021). Among the quantified elements, calcium and magnesium were found at comparatively higher concentrations, indicating their substantial role in structural and metabolic functions. These divalent cations are known to associate with the chitin matrix, possibly serving as ionic cross-linkers that enhance the rigidity, resilience, and mechanical strength of the exoskeletal structure. Their abundance in both the soil and mite tissues suggests a strong environmental availability and efficient biological uptake (Skubała et al. 2016). Iron plays a fundamental role in redox reactions, electron transport chains, and oxygen-binding mechanisms, while zinc is an essential cofactor for various metalloenzymes involved in cellular regulation, antioxidant defense, and cuticle formation. Furthermore, the elemental recovery percentages consistently exceeding 90% provide strong evidence for the analytical robustness and precision of the ICP-MS procedure. High recovery values indicate minimal loss during sample digestion and preparation, affirming the reliability of the method for trace and macroelement determination in complex biological and environmental samples. Overall, the elemental data obtained through ICP-MS analysis not only reinforce the successful integration of these metals into both environmental and biological systems but also offer valuable insights into the biochemical composition and adaptive strategies of oribatid mites (Skubała and Zaleski 2012.). Due to the limited biomass obtained from each species, ICP–MS analysis was performed on pooled samples of E. torulosus torulosus and A. (A.) acuta. The individual biomass of each species was insufficient to meet the minimum required quantity for accurate multi-element ICP–MS measurements. Pooling the two species allowed for reliable quantification of both trace and macroelements while ensuring reproducibility of the results.

It should be noted that the main objective of this analysis was to characterize the overall elemental composition of oribatid chitin rather than to compare species-specific differences. Interspecies variations had already been assessed separately using FTIR, SEM, and TGA/DTA analyses. Furthermore, both species were collected from the same microhabitat, ensuring that the pooled sample is representative of the overall elemental profile in that environment.

Overall, this study is the first to isolate and characterize chitin from E. torulosus torulosus and A. (A.) acuta. Using FTIR, TGA/DTA, SEM, and ICP-MS analyses, the study provides a comprehensive characterization of oribatid chitin and highlights the structural and functional importance of trace elements in the chitinous exoskeleton. These findings contribute valuable insights to the fields of environmental biogeochemistry, arthropod physiology, and biomaterial science.

Conclusion

This study presents the first comprehensive analysis combining structural characterization and elemental profiling of chitin isolated from oribatid mites and their soil microhabitats. The detailed investigation confirms the α-crystalline nature of mite-derived chitin and reveals distinct elemental accumulation patterns, underscoring the intricate ecological relationships between soil chemistry and microarthropod physiology. These novel insights not only advance the understanding of chitin as a key biomaterial in oribatid mites but also highlight its potential utility as a bioindicator for assessing environmental and geochemical conditions. Our integrated approach sets a foundation for future research exploring the functional and ecological significance of chitin in soil ecosystems.

Acknowledgements

The author would thank Fatma KILIÇ DOKAN for her help and support in the characterization analyses and Biologist Duygu ÇELİK for providing the material for this study.

References

- Anitha A., Sowmya S., Kumar P.S., Deepthi S., Chennazhi K., Ehrlich H., Tsurkan M., Jayakumar R. 2014. Chitin and chitosan in selected biomedical applications. Prog. Polym. Sci., 39 (9): 1644-1667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2014.02.008

- Arillo A., Subías L.S., Álvarez-Parra S. 2022. First fossil record of the oribatid family Liacaridae (Acariformes: Gustavioidea) from the lower Albian amber-bearing site of Ariño (eastern Spain). Cretac. Res., 131: 105087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2021.105087

- Arvanitoyannis I.S., Nakayama A, Aiba S. 1998. Chitosan and gelatin based edible films: state diagrams, mechanical and permeation properties. Carbohydr. Polym., 37: 371. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0144-8617(98)00083-6

- Behan-Pelletier, V.M. 1999. Oribatid mite biodiversity in agroecosystems: Role for bioindication. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 74, 411-423. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8809(99)00046-8

- Bough W.A. 1976. Shellfish components could represent future food ingredients. Process Biochem., 11: 13.

- Braconnot H. 1811. Recherches analytique sur la nature des champignons. Ann. Chim. Phys., 79, 265-304.

- Brugnerotto J., Lizardi J., Goycoolea F.M., Argüelles-Monal W., Desbrieres J., Rinaudo M. 2001. An infrared investigation in relation with chitin and chitosan characterization. Polymer, 42, 3569-3580. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-3861(00)00713-8

- Chitin J.B., Walton A.G., Blackwell J. 1973. Biopolymers, Academic Press, New York (1973), pp. 474-489.

- Cordes P.H., Maraun M., Schaefer I. 2022. Dispersal patterns of oribatid mites across habitats and seasons. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 86: 173-187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-022-00686-y

- Feketeová Z., Mangová B., Čierniková M. 2021. The Soil Chemical Properties Influencing the Oribatid Mite (Acari; Oribatida) Abundance and Diversity in Coal Ash Basin Vicinage. Appl. Sci., 11(8): 3537. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11083537

- Güneş E., Nizamlıoğlu H.F., Aydın H. 2018. Antioxidant Activity Of Chitin Obtained From The Insect. J. Int. Environmental Application & Science 13(4): 213-216.

- Gomes J.R.B., Jorge M., Gomes P. 2014. Interaction of chitosan and chitin with Ni, Cu and Zn ions: A computational study. J. Chem. Thermodyn., 73: 121-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jct.2013.11.016

- Hajji S., Ghorbelbellaaj O., Younes I., Jellouli K., Nasri M. 2015. Chitin extraction from crab shells by Bacillus bacteria. Biological activities of fermented crab supernatants. Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 79, 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.04.027

- Jang M.K., Kong B.G., Jeong Y.I., Lee C.H., Nah J.W. 2004. Physicochemical characterization of α-chitin, β-chitin, and γ-chitin separated from natural resources. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem., 42, 3423-3432. https://doi.org/10.1002/pola.20176

- Jeon Y.J., Shahidi F., Kim S.K. 2000. Preparation of chitin and chitosan oligomers and their applications in physiological functional foods. Food Rev. Int., 16 (2): 159-176. https://doi.org/10.1081/FRI-100100286

- Kaya M., Baran T. 2015. Description of a new surface morphology for chitin extracted from wings of cockroach (Periplaneta americana). Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 75, 7-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.01.015

- Kaya M., Bitim B., Mujtaba M., Koyuncu T. 2015a. Surface morphology of chitin highly related with the isolated body part of butterfly (Argynnis pandora). Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 81: 443-449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.08.021

- Kaya M., Mujtaba M., Bulut E., Akyuz B., Zelencova L., Sofi K. 2015b. Fluctuation in physicochemical properties of chitins extracted from different body parts of honeybee. Carbohydr. Polym., 132, 9-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.06.008

- Kaya M., Baran T., Asan-Ozusaglam M., Cakmak Y.S., Tozak K.O., Mol A., Mentes A., Sezen G. 2015c. Extraction and characterization of chitin and chitosan with antimicrobial and antioxidant activities from cosmopolitan Orthoptera species (Insecta). Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng., 20: 168-179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12257-014-0391-z

- Kaya M., Mujtaba M., Ehrlich H., Salaberria A.M., Baran T., Amemiya C.T., Galli R., Akyüz L., Sargin I., Labidi J. 2017. On Chemistry of γ-chitin. Carbohydr. Polym., 176: 177-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.08.076

- Kılcı L., Nurver A., Karaoglu Ş.A., Yesildal T.K. 2024. Characterization of chitin and description of its antimicrobial properties obtained from Cydalima perspectalis adults. Polym. Bull., 81:14217-14234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-024-05381-z

- Kim M.W., Han Y.S., Jo Y.H., Choi M.H., Kang S.H., Kim S.A., Jung W.J. 2016. Extraction of chitin and chitosan from housefly, Musca domestica, pupa shells. Entomol. Res. 46: 324-328. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-5967.12175

- Knorr D. 1991. Recovery and Utilization of Chitin and Chitosan in Food Processing Waste Management. Food Technol., 45(1): 114

- Krantz G.W., Walter D.E. 2009. A manual of Acarology. Third Edition. Texas Tech University Press, Lub-bock, Texas, USA, 807 pp.

- Lavall R.L., Assis O.B.G., Campana-Filho S.P. 2007. Beta-chitin from the pens of Loligo sp.: extraction and characterization. Bioresour. Technol., 98: 2465-2472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2006.09.002

- Moitra M.N. 2013. On variation of diversity of soil oribatids (Acari, Oribatida) in three differently used soil habitats-a waste disposal site, a natural forest and a tea garden in the northern plains of Bengal, India, Int. J. Sci. Res. Publications., 3(11): 1-12.

- Nemtsev S.V., Zueva O.Y., Khismatullin M.R., Albulov A.I., Varlamov V.P. 2004. Isolation of chitin and chitosan from honeybees. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol., 40: 39-43. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:ABIM.0000010349.62620.49

- Nguyen T.T., Zhang W., Barber A.R., Su P., He S. 2016. Microwave-intensified enzymatic deproteinization of Australian rock lobster shells (Jasus edwardsii) for the efficient recovery of protein hydrolysate as food functional nutrients. Food Bioprocess Technol., 9: 628-636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-015-1657-y

- No H.K., Meyers S.P, Lee K.S. 1989. Isolation and Characterization of Chitin from Crawfish Shell Waste. J. Agric. Food Chem., 37: 575 https://doi.org/10.1021/jf00087a001

- Odote O., Struszczyk M., Peter G.M. 2007. Characterisation of chitosan from blowfly larvae and some crustacean species from Kenyan Marin waters prepared under different conditions. West. Indian Ocean J. Mar. Sci., 4: 99-107. https://doi.org/10.4314/wiojms.v4i1.28478

- Percot A., Viton C., Domard A. 2003. Optimization of chitin extraction from shrimp shells. Biomacromolecules., 4: 12-18. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm025602k

- Rinaudo M. 2006. Chitin and chitosan: Properties and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 31 (7): 603-632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2006.06.001

- Subías L.S. 2004. Systematic, synonimical and biogeographical check-list of the world's oribatid mites (Acariformes, Oribatida) (1758-2002). Graellsia, 60 (1): 3-305. (actualizado en junio de 2006, en abril de 2007, en mayo de 2008, en abril de 2009, en julio de 2010, en febrero de 2011, en abril de 2012, en mayo de 2013 y en febrero de 2014, en marzo de 2015 y en febrero de 2016, en febrero de 2017, en enero de 2018, en marzo de 2019, en enero de 2020 y en marzo de 2021). [In Spanish]

- Skubała P., Zaleski T. 2012. Heavy metal sensitivity and bioconcentration in oribatid mites (Acari, Oribatida): Gradient study in meadow ecosystems, Sci. Total Environ., 414: 364-372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.11.006

- Skubała P., Rola K., Osyczka P. 2016. Oribatid communities and heavy metal bioaccumulation in selected species associated with lichens in a heavily contaminated habitat. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int., 23(9): 8861-71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-6100-z

- Wissuwa J., Salamon J.A., Frank T. 2013. Oribatida (Acari) in grassy arable fallows are more affected by soil properties than habitat age and plant species. Eur. J. Soil Biol., 59: 8-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2013.08.002

- Zhao D., Huang W.C., Guo N., Zhang S., Xue C., Mao X. 2019. Two-Step Separation of Chitin from Shrimp Shells Using Citric Acid and Deep Eutectic Solvents with the Assistance of Microwave. Polymers, 11(3): 409. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11030409

2025-06-27

Date accepted:

2025-11-07

Date published:

2025-11-13

Edited by:

Baumann, Julia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

2025 Per, Sedat

Download the citation

RIS with abstract

(Zotero, Endnote, Reference Manager, ProCite, RefWorks, Mendeley)

RIS without abstract

BIB

(Zotero, BibTeX)

TXT

(PubMed, Txt)