Reconsidering the hierarchic position of the family Dytiscacaridae Hajiqanbar and Lindquist: A proposal for its placement as a separate superfamily within Raphignathina

Doğan, Salih  1

; Koç, Kamil

1

; Koç, Kamil  2

; Ueckermann, Edward A.

2

; Ueckermann, Edward A.  3

and Lindquist, Everet E.

3

and Lindquist, Everet E.  4

4

1Department of Biology, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Erzincan Binali Yıldırım University, Türkiye.

2Department of Biology, Faculty of Engineering and Natural Sciences, Manisa Celal Bayar University, Türkiye.

3✉ Unit for Environmental Sciences and Management, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa.

4Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, Science and Technology Branch, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

2024 - Volume: 64 Issue: 3 pages: 968-975

https://doi.org/10.24349/tnsp-6s7eZooBank LSID: F35204FB-0F53-45E1-8297-9384445A2598

Original research

Keywords

Abstract

Introduction

The cohort or hyporder Raphignathina formerly comprised six superfamilies with about 5649 described species accommodated in approximately 450 genera (Koç et al., 2023). This cohort includes plant parasites, animal parasites, and free-living predators. Mortazavi et al. (2018) described the family Dytiscacaridae Hajiqanbar and Lindquist based on the genus Dytiscacarus Hajiqanbar and Lindquist, 2018, and placed it in the superfamily Raphignathoidea within the Raphignathina. This lineage is unique among parasitic mites in that there are no previous records of aquatic beetles harbouring all instars of a highly specialised mite (Mortazavi et al., 2018). According to Mortazavi et al. (2018), the distinctive features of the family Dytiscacaridae could warrant its recognition as a superfamily, separate from the Raphignathoidea. We here formally propose that change, based on a detailed comparison of the Dytiscacaridae with the other superfamilies of Raphignathina.

Material and methods

This study is based on an analysis of the literature dealing with the family Dytiscacaridae Hajiqanbar and Lindquist. Further observations of reference specimens were not made, and no further collection records were added. Our study of the biology and morphology of the family, as well as its similarities and differences with the related groups, was based on previous studies as revealed by a comprehensive study of the literature (e.g., Lindquist, 1984; Lindquist and Kethley, 1975; Bochkov, 2002; Fan and Zhang, 2005; Bochkov and OConnor, 2006, 2008; Bochkov et al., 2008; Mironov and Bochkov, 2009; Walter et al., 2009; Mortazavi et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2011). The classification system used here follows Lindquist et al. (2009), Walter et al. (2009) and Zhang et al. (2011).

Results

Family Dytiscacaridae Hajiqanbar and Lindquist, in Mortazavi et al. (2018)

Genus Dytiscacarus Hajiqanbar and Lindquist, in Mortazavi et al. (2018)

Included species

● Dytiscacarus iranicus Mortazavi and Hajiqanbar, in Mortazavi et al. (2018)

● Dytiscacarus americanus Mortazavi and Hajiqanbar, in Mortazavi et al. (2018)

● Dytiscacarus thermonecti Mortazavi and Hajiqanbar, in Mortazavi et al. (2018)

Current taxonomic status of Dytiscacaridae

This family belongs to the suborder Prostigmata in the order Trombidiformes, because it has a well-developed tracheal system with a pair of stigmata near the cheliceral bases in the gnathosoma and no evidence of a caudal bend in the idiosoma. Dytiscacaridae is not included in the supercohorts or infraorders Labidostommatides, Eupodides or Anystides, because the chelicera lacks developed or residual fixed digits in contrast to non-retractable movable digits. It is further excluded from those groups by having just two nymphal instars, which lack some postlarval caudal somal additions (e.g., absence of anal and peranal setae), and by lacking larval urstigmata and postlarval genital papillae (Mortazavi et al., 2018). Dytiscacaridae is placed in the Eleutherengonides by its retractable stylet-like movable digits, the lack of fixed cheliceral digits, and the lack of larval urstigmata, postlarval genital papillae, and adult ovipositor. The lack of prodorsal bothridia, the shape of the movable cheliceral digits, the presence of stigmata on the gnathosoma, and absence of genital papillae, show that it fits the cohort or hyporder Raphignathina. It has enough morphological resemblance to the superfamily Raphignathoidea to be considered derived from or originating within Raphignathoidea (Mortazavi et al., 2018). However, because of the autapomorphic features of this family as detailed by Mortazavi et al. (2018), we propose a separate superfamilial rank within the Raphignathina for this unique family. The reasons for this proposition are summarised below.

Dytiscacarids and related groups

Assessment according to morphological characteristics

The family Dytiscacaridae is assigned to the supercohort or infraorder Eleutherengonides. However, it is a little more controversial to place this group in either of the two cohorts or hyporders that make up the Eleutherengonides, Raphignathina and Heterostigmatina (Mortazavi et al., 2018). The family is related to Heterostigmatina in that it has linear palps without a palpal thumb-claw process, a sequence of dorsal opisthosomatic plates (tergites) in all instars, and considerable sexual dimorphism, with males having a well-developed genital capsule (Mortazavi et al., 2018). Also, heterostigmatine females are autapomorphic in usually having a pair of prodorsal setae modified as capitate trichobothria, and rarely also in males, but not in immature instars.

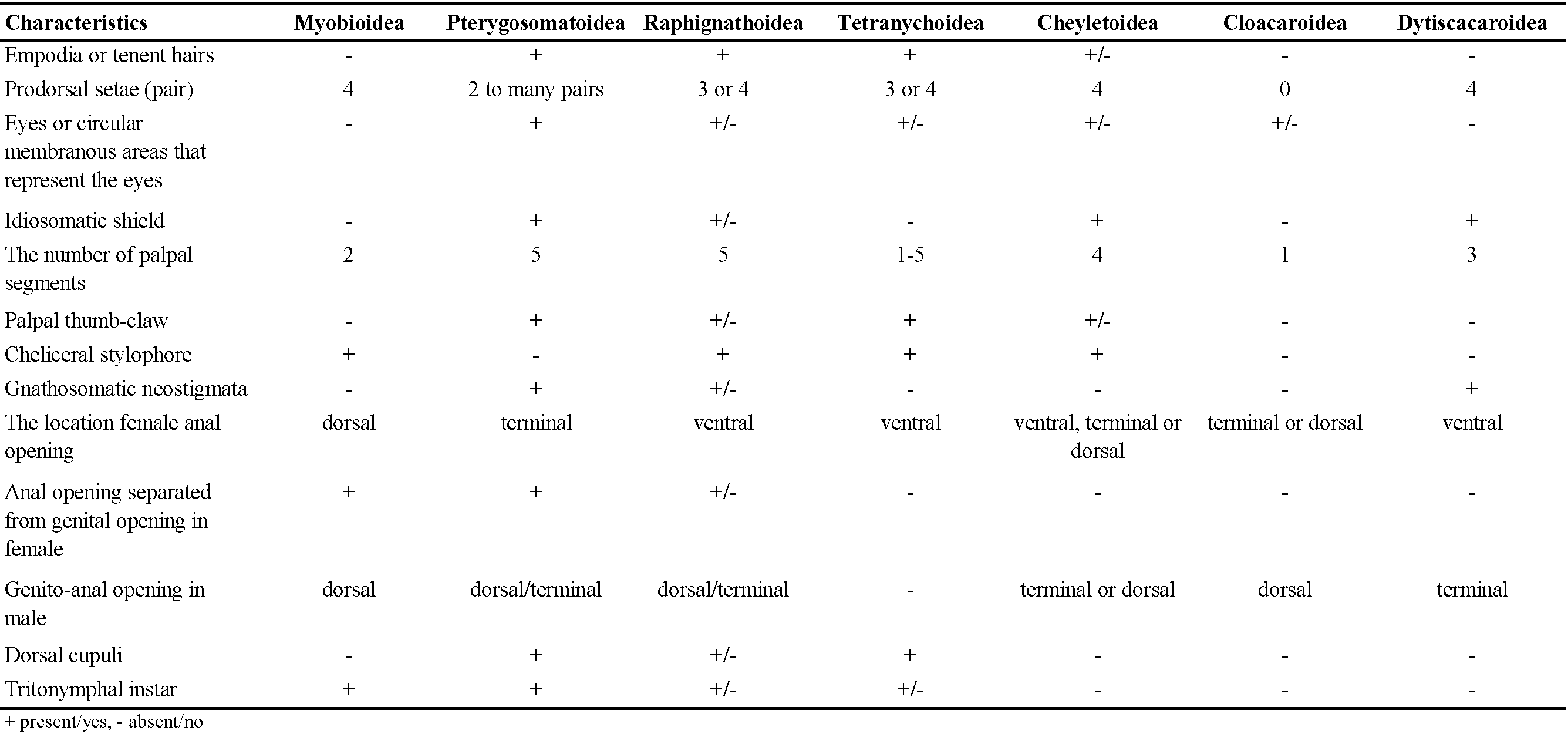

The family Dytiscacaridae has several characteristics that suggest it fits better within the cohort or hyporder Raphignathina, according to Mortazavi et al. (2018). However, because morphological aspects of the gnathosoma, dorsal idiosoma and leg tarsi of Dytiscacaridae are uniquely modified, it is difficult to relate Dytiscacaridae to any of the six superfamilies of Raphignathina (Cheyletoidea, Cloacaroidea, Myobioidea, Pterygosomatoidea, Raphignathoidea, Tetranychoidea). The differences mentioned below are mainly based on Mortazavi et al. (2018), following Lindquist et al. (2009).

Dytiscacaridae is easily separated from the Cheyletoidea due to its lack of a cheliceral stylophore. In Cheyletoidea, the gnathosoma is consolidated into a gnathosomal capsule. In a further distinction, Dytiscacaridae has a pair of autapomorphic gnathosomatic neostigmata, and its legs have apomorphically highly modified claws, whereas cheyletoids plesiomorphically do not bear gnathosomatic neostigmata and atedhave a pair of hooked claws on tarsus II and typically on tarsi III-IV, unless their legs are reduced or absent. Dytiscacaridae bear reduced, three-segmented palps lacking a thumb-claw process, whereas in cheyletoids the palps sometimes have a fused tibiotarsus and femorogenu, and a tibial claw is present. However, this does not hold for some parasitic cheyletoids.

Dytiscacaridae is different from the Cloacaroidea in that the genital aperture is a longitudinal slit between coxae III and IV, and nearly contiguous with the anal opening. In Cloacaroidea the genital and anal openings are completely fused and are situated ventrally, terminally or dorsally. In Dytiscacaridae, the legs are six-segmented, coxae are not completely fused with the idiosoma, and coxal apodemes are well-developed but shorter than half the width of the idiosoma. In the Cloacaroidea the legs have three articulated segments, the coxae are completely fused with the idiosoma, and the coxal apodemes are longer than half the width of the body. The gnathosoma is projected apically beyond the bases of legs I in Dytiscacaridae, with three-segmented palps bearing several tiny setae, and stigmata leading to neostigmata, whereas in Cloacaroidea the gnathosoma is in a ventral position between bases of legs I, with one-segmented palps bearing several spine-like setae, and uncertainty about stigmata (no mention is made about stigmata by Bochkov and OConnor, 2008).

The Myobioidea is defined apomorphically by the chelicerae and infracapitulum merged to form a retractile gnathosomatic capsule inside the idiosoma, the dorsal aedeagus in males and dorsal-terminal anal opening in females, leg I adapted for grabbing mammalian host hairs, with merged genua and femora on all legs of the juvenile instars. In Dytiscacaridae, a retractable gnathosomatic capsule is not formed, the genito-anal opening is terminal in males and ventral in females, leg I is similar to the other legs, and the genua and femora of all legs are not merged in all postembryonic instars. In addition, Myobioidea has two-segmented palps, and idiosomatic shields are absent. Dytiscacaridae has three-segmented palps and dorsal plates are present.

The Pterygosomatoidea develop a complete ontogenetic sequence, comprising three nymphal instars with an alternating calyptostase reminiscent of the Parasitengonina; the peritremes freely protrude dorsally from the bases of the chelicerae, the palps bear a well-developed thumb-claw process, and the gnathosoma has independently moving cheliceral bases with hook-like, non-retractable, movable cheliceral digits. Dytiscacarids have two nymphal instars and lack inactive phases in their life cycle; they have no peritremes, lack a palpal thumb-claw formation and have movable stylet-like cheliceral digits that can be retracted deeply into the proterosoma. Moreover, Pterygosomatoidea has five-segmented palps, and all legs terminate with an empodium or tenent hairs. Dytiscacaridae has three-segmented palps, and the legs lack empodia or tenent hairs.

The Tetranychoidea are characterised autapomorphically by the fusion of the cheliceral bases into a moveable stylophore that is deeply retractable into the idiosoma; with retractable cheliceral stylets that are long and whip-like, recurved basally within the stylophore. Tetranychoids additionally differ in that the male aedeagus is not enclosed in a genital capsule, and they primitively have paired claws with variously formed empodial structures. Comparative characteristics of the superfamilies belonging to the cohort Raphignathina are given in Table 1.

The current placement of Dytiscacaridae in the Raphignathoidea is challenged by the presence of a stylophore formed by the cheliceral bases in the families Caligonellidae, Camerobiidae, Dasythyreidae, Raphignathidae and Xenocaligonellididae; the presence of a hood-like extension of the prodorsum and a gnathosoma can be retracted into the propodosoma in Cryptognathidae; stigmatic openings present at base of chelicerae (Caligonellidae, Camerobiidae, Dasythyreidae and Xenocaligonellididae) or absent (Stigmaeidae, Homocaligidae, Eupalopsellidae, and Mecognathidae); palps five-segmented with thumb-claw process usually present but often weakly developed (ex Eupalopsellidae); cheliceral bases usually swollen (ex Cryptognathidae and some Stigmaeidae); empodial elements of the tarsi commonly with tenent hairs, claws usually present on all legs (padlike in some Stigmaeidae), tenent hairs lacking on all claws except Barbutiidae; males with an aedeagus simple or complex (ex Cheylostigmaeus, Stigmaeidae) but free in body.

All active instars of Dytiscacaridae have a pair of neostigmata that open directly onto the dorsal surface of the infracapitulum. They bear three-segmented palps without a thumb-claw process and do not bear a hood-like extension of the gnathosoma. The instars of Dytiscacaridae do not have empodial structures between the bases of the paired tarsal claws, in contrast to the families of Raphignathoidea. Despite the absence of any empodial structure in the tarsi of legs I-IV within Dytiscacaridae, the paired claws bear some resemblance to those of the family Barbutiidae due to their two pairs of tenent-like structures. But given that the tenent-like structures of Dytiscacaridae have extremely well-formed, sclerotised hooks, and that barbutiids have finer structures, which are also present in some other taxa of Raphignathina, such as Tetranychoidea, these characteristics are most likely independently developed. The male of Dytiscacaridae has a well-developed genital capsule, but the aedeagus is not housed in a genital capsule in Raphignathoidea.

The prodorsal shields in matures and immatures of Dytiscacaridae are at least partially merged with the anteriormost shields of the opisthosoma, resulting in the coexistence of prodorsal and tergital D setal elements on the same shields (Mortazavi et al., 2018). In the family Raphignathidae, there is a somewhat similar arrangement. The larvae and nymphs of Dytiscacarus and Raphignathus have an obovate anteromedial dorsal shield between two lateral shields. The setal elements of the prodorsum and somite C are located on each lateral shield, arranged so that at least one of the two prodorsal scapular setae (sce) and one of the two tergite C setae (c2) are present together. Unlike those of Dytiscacarus, most species of Raphignathus have setae of the d, e, f, h series located on a large dorsal opisthosomatic shield. However, some species of Raphignathus may have a small dorsal opisthosomatic shield such that setae d or d and e are on striated soft cuticle known as ''interscutal membrane″. In any case, the adult female of Raphignathus, unlike Dytiscacarus, has the anterior shield separated from the posterior one by soft striated integument. In males of Raphignathus, the anterior three shields are combined into a single shield, which may be partially integrated or separate from an extensive opisthosomatic shield. If the shields are partially merged, soft cuticular incisions divide them laterally, similar to those of males of Dytiscacarus. As a result, the setal homologies of the dorsal shields in Dytiscacarus and Raphignathus should be considered superficial. In Dytiscacarus, on the other hand, the neostigmata open on the exposed dorsal face of the infracapitulum, but in Raphignathus, they open on a basal fissure of the stylophore. In addition, Raphignathus has thin, slightly retractable stylets; in contrast, the stylets of Dytiscacarus are much more elongated, fully retractable, and deeply into the proterosoma, each apparently capable of being extruded independently. The stylets of Raphignathus remain apical, opposed by pointed, hyaline extensions of the fixed digits protruding from the stylophore. Finally, there is no specific similarity between Raphignathus and Dytiscacarus′ leg setations, and the mites of these two taxa are very different in form and lifestyle (Mortazavi et al., 2018).

Assessment according to the lifestyle and microhabitat

The superfamily Myobioidea are usually ectoparasites on marsupial, rodent, bat, elephant shrew and eulipotyphlan insectivore hosts, with legs I modified as clasping organs. Larva, deutonymph and adult of Pterygosomatoidea are parasites of lizards, tortoises, scorpions, and various insects. Members of the Cloacaroidea are specialised endoparasites of vertebrates (Bochkov and OConnor, 2008). The superfamily Tetranychoidea are obligatory phytophages, often important as plant pests. Species of Cheyletoidea are ectoparasites of birds, mammals, and insects. More often they are free-living predators on other mites, first instar armoured scale insects, and other small insects (Walter et al., 2009).

The majority of the raphignathoid mites are free-living predators (Fan and Zhang, 2005). But three identified species of Stigmaeus and six identified and one unidentified species of the genus Eustigmaeus, belonging to the family Stigmaeidae, parasitise hematophagous phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) (Swift, 1987; Fan and Zhang, 2005; Mortazavi et al., 2018; Pekağırbaş et al., 2023). The feeding scars and lesions seen on the hosts' bodies are signs that these mites are parasites. These mites' digestive tracts do not have any direct evidence of host hemolymph, and the effect they have on the host flies has not been assessed. Furthermore, no reports of males or immature mites on the hosts have been made, raising doubts about their parasitic lifestyle (Mortazavi et al., 2018; Doğan and Doğan, 2024). Nonetheless, the Dytiscacaridae are highly specialised parasites of beetles in the family Dytiscidae, and they live beneath their hosts' elytra throughout their whole life cycle (including eggs), (Mortazavi et al., 2018). While the other lineage continued to live freely, Dytiscacaridae appears to have significant morphological alterations associated with adapting to a parasitic lifestyle. We are not arguing that dytiscacarids need their own superfamily simply because they are parasitic. Certainly, some lineages may develop parasitism; however, overall this is weak evidence because specialised forms can occur even at lower levels in many mite taxa. At best, the dytiscacarids may be a sister group to the Raphignathoidea in Raphignathina and are currently best classified as a separate group at the superfamily level.

Dytiscacarid mites are thought to be related to raphignathoids, but their habitats are somewhat different. Dytiscacarids living on dytiscid beetles are completely aquatic. The majority of raphignathoid mites are found in xeric edaphic microhabitats; however, certain species such as those of Annerossella and Homocaligus of Homocaligidae, and Caligohomus, Cheylostigmaeus, Eustigmaeus and Ledermuelleriopsis of Stigmaeidae, are semi-aquatic living in fresh-water (such as ponds, quiet streams, and marshes) (Fan and Zhang, 2005).

Recognition of a new superfamilial rank

According to Mortazavi et al. (2018), all the above-mentioned differences between the superfamilies in the Raphignathina provide support for classifying Dytiscacaridae as belonging to a separate superfamily. We here formally recognise the family Dytiscacaridae at superfamilial rank, as Dytiscacaroidea Hajiqanbar and Lindquist, 2018, in accordance with the Principle of Coordination within the family group (Article 36.1, International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, 4th ed., 1999).

Diagnosis

The morphological arrangement of the stylet-like movable cheliceral digits deeply retractable into proterosoma, the presence of a pair of gnathosomatic neostigmata on the dorsal face of the infracapitulum, and the pretarsi of all legs—which lack an empodium and bear paired lateral claws that are strongly modified into sclerotised tenent-like structures—are characteristics of all active instars, and males of Dytiscacaroidea have a genital capsule encasing strongly formed genitalia (Mortazavi et al., 2018).

Current superfamilies of the cohort or hyporder Raphignathina

● Superfamily: Cheyletoidea Leach, 1816

● Superfamily Cloacaroidea Camin, Moss, Oliver and Singer, 1967; incertae sedis sensu Zhang et al., 2011

● Superfamily Dytiscacaroidea Hajiqanbar and Lindquist, 2018

● Superfamily Myobioidea Mégnin, 1877

● Superfamily Pterygosomatoidea Oudemans, 1910

● Superfamily Raphignathoidea Kramer, 1877

● Superfamily Tetranychoidea Donnadieu, 1875

Conclusion

Recognition of the genus Dytiscacarus and family Dytiscacaridae to represent a proposed superfamily is based on the morphological rationale presented in Mortazavi et al. (2018) as to its sister relationships among other superfamilies of the cohort or hyporder Raphignathina. It is evident that the morphological form and habits of dytiscacarid mites greatly differ from those of all other raphignathoid families. Until a molecular phylogenetic analysis is conducted, we believe that the comparative morphological characteristics of Dytiscacaridae with closely related groups, discussed in detail by Mortazavi et al. (2018), suffice to classify it in the cohort or hyporder Raphignathina as a different superfamily distinguished from other superfamilies of Raphignathina.

It is worth noting here that although the classification of lower taxa is generally not very contentious, there may be disagreements about the classification of higher taxa including mites, based on classical morphological and molecular data, as is the case with arthropods in general (Blaxter, 2001; Lindquist et al., 2009). The recognition of a new superfamilial rank for Dytiscacaroidea Hajiqanbar and Lindquist, 2018 will become clear in future taxonomic studies and by reaching general consensus among practising taxonomists working on mites.

Statement of ethics approval

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare about the subject matter of this study.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Alexander Alexandrovich Khaustov (University of Tyumen, Russia), Bruce Halliday (Australian National Insect Collection, Australia), Farid Faraji (Eurofins MITOX, The Netherlands), Owen Seeman (Queensland Museum, Australia), Qing-Hai Fan (Ministry for Primary Industries, New Zealand) and the anonymous reviewers for their adding value to this publication.

References

- Blaxter M. 2001. Evolutionary biology. Sum of the arthropod parts. Nature, 413: 121-122. https://doi.org/10.1038/35093191

- Bochkov A.V. 2002. The classification and phylogeny of the mite superfamily Cheyletoidea (Acari, Prostigmata). Entomol. Obozr., 81: 488-513. [In Russian] - Entomol. Rev, 82: 643-664. [In English]

- Bochkov A.V., OConnor B.M. 2006. A review of the external morphology of the mite family Pterygosomatidae and its systematic position within the Prostigmata (Acari: Acariformes). Parazitologiya, 40 (3): 201-214. [In Russian]

- Bochkov A.V., OConnor B.M. 2008. A new mite superfamily Cloacaroidea and its position within the Prostigmata (Acariformes). J. Parasitol., 94 (2): 335-344. https://doi.org/10.1645/GE-930.1

- Bochkov A.V., OConnor B.M., Wauthy G. 2008. Phylogenetic position of the mite family Myobiidae within the infraorder Eleutherengona (Acariformes) and origins of parasitism in eleutherengone mites. Zool. Anz., 247 (1): 15-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcz.2006.12.003

- Camin J.H., Moss W.W., Oliver J.H. Jr., Singer G. 1967. Cloacaridae, a new family of the Cheyletoidea mites from the cloaca of aquatic turtles (Acari: Acariformes: Eleutherengona). J. Med. Entomol., 4 (3): 261-272. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/4.3.261

- Doğan S., Doğan S. 2024. Taxonomic comments on some species of the genus Eustigmaeus Berlese (Trombidiformes: Stigmaeidae), with a revised checklist of Eustigmaeus and descriptions of two new species from Türkiye. Acarologia, 64 (3): 711-732. https://doi.org/10.24349/e3fo-3y3r

- Donnadieu A.L. 1875. Recherches pour server á l'histoirie des Tétranyques. Thèses - Faculté des Sciences de Lyon, France, 134 pp.

- Fan Q.-H., Zhang Z.-Q. 2005. Raphignathoidea (Acari: Prostigmata). Fauna of New Zealand 52. Manaaki Whenua Press, Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand, 400 pp. https://doi.org/10.7931/J2/FNZ.52

- ICZN 1999. International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. Fourth edition. International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature, London, UK, 306 pp.

- Koç K., Çobanoğlu S., Özman-Sullivan S.K., Esen Y. 2023. Takım: Trombidiformes. In: Doğan S. and Özman-Sullivan S.K. (Eds), Genel akaroloji. Nobel Akademik Yayıncılık, Ankara, Türkiye, 557-584. [In Turkish]

- Kramer P. 1877. Grundzüge zur Systematik der Milben. Arch. Naturgesch., 43: 215-247.

- Leach W.E. 1816. A tabular view of the external characters of four Classes of Animals, which Linné arranged under Insecta; with the distribution of the genera composing three of these Classes into Orders, &c. and descriptions of several new genera and species. Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond., 11: 306-400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1813.tb00065.x

- Lindquist E.E. 1984. Current theories on the evolution of major groups of Acari and on their relationships with other groups of Arachnida, with consequent implications for their classification. In: Griffiths D.A. and Bowman C.E. (Eds), Acarology VI. Vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons, New York, USA, 28-62.

- Lindquist E.E., Kethley J.B. 1975. The systematic position of the Heterocheylidae Trägårdh (Acari: Acariformes: Prostigmata). Can. Entomol., 107: 887-898. https://doi.org/10.4039/Ent107887-8

- Lindquist E.E., Krantz G.W., Walter D.E. 2009. Classification. In: Krantz G.W. and Walter D.E. (Eds), A manual of acarology. Third edition. Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock, Texas, USA, 97-103.

- Mégnin J.P. 1877. Monographie de la tribu des sarcoptides psoriques qui comprend tous les acariens de la gale de l′homme et des animaux. Revue Mag. Zool., 3 (5): 46-213.

- Mironov S.V., Bochkov A.V. 2009. Modern conceptions concerning the macrophylogeny of acariform mites (Chelicerata, Acariformes). Zool. Zhurnal, 88: 922-937. [In Russian] - Entomol. Rev., 89: 975-992. [In English] https://doi.org/10.1134/S0013873809080120

- Mortazavi A., Hajiqanbar H., Lindquist E.E. 2018. A new family of mites (Acari: Prostigmata: Raphignathina), highly specialised subelytral parasites of dytiscid water beetles (Coleoptera: Dytiscidae: Dytiscinae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc., 184 (3): 695-749. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlx113

- Oudemans A.C. 1910. A short survey of the more important families of Acari. Bull. Entomol. Res., 1: 105-119. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485300042905

- Pekağırbaş M., Karakuş M., Yılmaz A., Erişöz Kasap Ö., Sevsay S., Özbel Y., Töz S., Doğan S. 2023. Two parasitic mite species on Phlebotominae sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) from Türkiye: Biskratrombium persicum (Microtrombidiidae) and Eustigmaeus johnstoni (Stigmaeidae). Acarol. Stud., 5 (1): 11-16. https://doi.org/10.47121/acarolstud.1209774

- Swift S.F. 1987. A new species of Stigmaeus (Acari: Prostigmata: Stigmaeidae) parasitic on phlebotomine flies (Diptera: Psychodidae). Int. J.Acarol., 13 (4): 239-243. https://doi.org/10.1080/01647958708683778

- Walter D.E., Lindquist E.E., Smith I.M., Cook D.R., Krantz G.W. 2009. Order Trombidiformes. In: Krantz G.W. and Walter D.E. (Eds), A manual of acarology. Third edition. Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock, Texas, USA, 233-420.

- Zhang Z.-Q., Fan Q.-H., Pesic V., Smit H., Bochkov A.V., Khaustov A.A., Baker A.S., Woltmann A., Wen T., Amrine J.W., Beron P., Lin J., Gabrys G., Husband R. 2011. Order Trombidiformes Reuter, 1909. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.), Animal biodiversity: an outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness. Zootaxa, 3148: 129-138. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.24

2024-06-17

Date accepted:

2024-09-02

Date published:

2024-09-10

Edited by:

Faraji, Farid

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

2024 Doğan, Salih; Koç, Kamil; Ueckermann, Edward A. and Lindquist, Everet E.

Download the citation

RIS with abstract

(Zotero, Endnote, Reference Manager, ProCite, RefWorks, Mendeley)

RIS without abstract

BIB

(Zotero, BibTeX)

TXT

(PubMed, Txt)