DNA barcoding, visual-guide resource, new localities and host associations of genus Periglischrus Oudemans, 1902 (Acari: Mesostigmata, Spinturnicidae) from Minas Gerais, Brazil

Gomes-Almeida, Brenda Karolina  1

; Diório, Gabriel Félix

1

; Diório, Gabriel Félix  2

; Costa, Samuel Geremias dos Santos

2

; Costa, Samuel Geremias dos Santos  3

and Pepato, Almir Rogério

3

and Pepato, Almir Rogério  4

4

1✉ Pós-graduação em Zoologia & Laboratório de Sistemática e Evolução de Ácaros Acariformes, Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). Av. Antônio Carlos, 6627, Pampulha, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

2Laboratório de Sistemática e Evolução de Ácaros Acariformes, Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). Av. Antônio Carlos, 6627, Pampulha, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

3Pós-graduação em Zoologia & Laboratório de Sistemática e Evolução de Ácaros Acariformes, Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). Av. Antônio Carlos, 6627, Pampulha, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil & X-BIO institute, Tyumen State University, Semakova Str., 10, Tyumen, 625003 Russia.

4Laboratório de Sistemática e Evolução de Ácaros Acariformes, Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). Av. Antônio Carlos, 6627, Pampulha, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil & X-BIO institute, Tyumen State University, Semakova Str., 10, Tyumen, 625003 Russia.

2024 - Volume: 64 Issue: 2 pages: 425-462

https://doi.org/10.24349/hrkz-fmo3Original research

Keywords

Abstract

Introduction

The cosmopolitan family Spinturnicidae (Oudemans, 1902) includes hematophagous mites found exclusively as ectoparasites on bats. Their life cycle comprises five stages, all occurring on the host: egg, larva, protonymph, deutonymph, and adult. Of these, the egg and larval stages occur inside the pregnant female (Rudnick 1960), nymphs and adults mostly inhabit the plagiopatagium of bats (Almeida et al. 2015).

Currently, Spinturnicidae comprises 12 genera and 110 species (Beron 2020). Among genera, five occur across Americas, associated more or less specifically with four bat families: Cameronieta Machado-Allison, 1965b with Mormoopidae; Periglischrus Kolenati, 1857 with Phyllostomidae; Spinturnix Von Heyden, 1826, a cosmopolitan genus, with Vespertilionidae bats, Paraspinturnix Rudnick, 1960, a monotypic genus, associated with the anal orifice of bats belonging to the genus Myotis (Vespertilionidae); and Mesoperiglischrus Dusbábek, 1968 associated with Natalidae (Dusbábek 1968; Herrin and Tipton 1975; Morales-Malacara 2001; Von Heyden 1826.). Except for Paraspinturnix, all of these genera are recorded from Brazil (Kolenati 1857; Oudemans 1902, 1903; Rudnick 1960; Confalonieri 1976; Gettinger and Gribel 1989; Azevedo et al. 2002; Almeida et al. 2007, 2011, 2015, 2016a, 2016b, 2018; Dantas-Torres et al. 2009; Silva et al. 2009, 2017; Silva and Graciolli 2013; Moras et al. 2013; Lourenço et al. 2016; Bezerra and Bocchiglieri 2018; Lourenço et al. 2020; Vidal et al. 2021).

Periglischrus includes 26 species recorded from Neotropics (Morales-Malacara and López-Ortega 2023). Some closely related species are similar enough to make accurate identification difficult. Some authors proposed species groups (e.g., acutisternus species group proposed by Morales-Malacara 2001) according to morphological similarity and affinity to their Phyllostomidae bat hosts. Host specificity ranges from monoxenous (a single host species), stenoxenous (a single host genus) to oligoxenous (occur in two or more host genera of the same family) (Herrin and Tipton 1975; Morales-Malacara 2001).

Thus far, fourteen species have been recorded in Brazil (Almeida et al. 2016b; Silva et al. 2017; Lourenço et al. 2020): Periglichrus acutisternus Machado-Allison, 1964, P. caligus Kolenati, 1857, P. herrerai Machado-Allison, 1965a, P. hopkinsi Machado-Allison, 1965a, P. iheringi Oudemans, 1902, P. micronycteridis Furman, 1966, P. ojastii Machado-Allison, 1964, P. paracutisternus Machado-Allison & Antequera, 1971, P. paravargasi Herrin & Tipton, 1975, P. parvus Machado-Allison, 1964, P. ramirezi Machado-Allison & Antequera, 1971, P. tonatii Herrin & Tipton, 1975, P. torrealbai Machado-Allison, 1965a, and P. vargasi Hoffmann, 1944 (Hoffmann 1944).

Because some Periglischrus species are similar enough to make morphological identification difficult (Morales-Malacara 2001) or show extensive intraspecific phenotypic variation related to host species (Almeida et al. 2018; Morales-Malacara et al. 2018, 2020; Zamora-Mejías et al. 2022), the inclusion of molecular data and careful specimen documentation is useful to make identification and occurrence ranges more reliable and reproducible.

The convergence of different methodologies, such as biological or breeding studies, morphometrics and statistical analyses, and molecular tools with traditional taxonomy is a desirable scenario (Łaydanowicz and Makol 2010; Dabert et al. 2011), conducted as part of an integrative taxonomic approach (Knowles and Carstens 2007; Schlick-Steiner et al. 2010).

Herewith, we generated and made available DNA barcoding sequences and high-resolution photographs in the BOLD (Barcoding of Life Data System v4) database (Ratnasingham and Hebert 2007) of six species of Periglichrus collected on 11 bat species obtained from Minas Gerais state and provided a visual guide to the diagnostic characters useful to their identification.

Material and methods

Specimen sampling, preservation and licenses

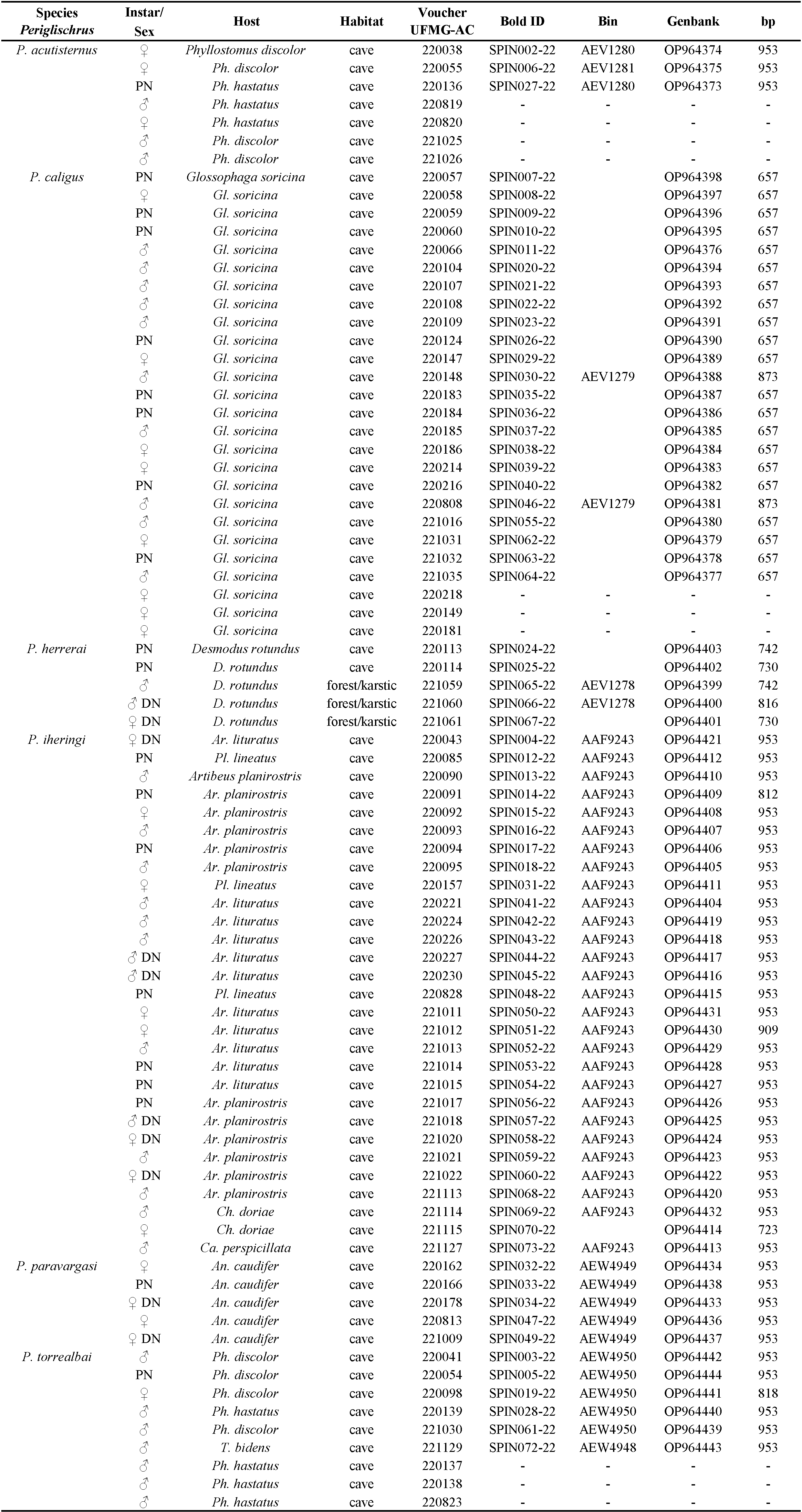

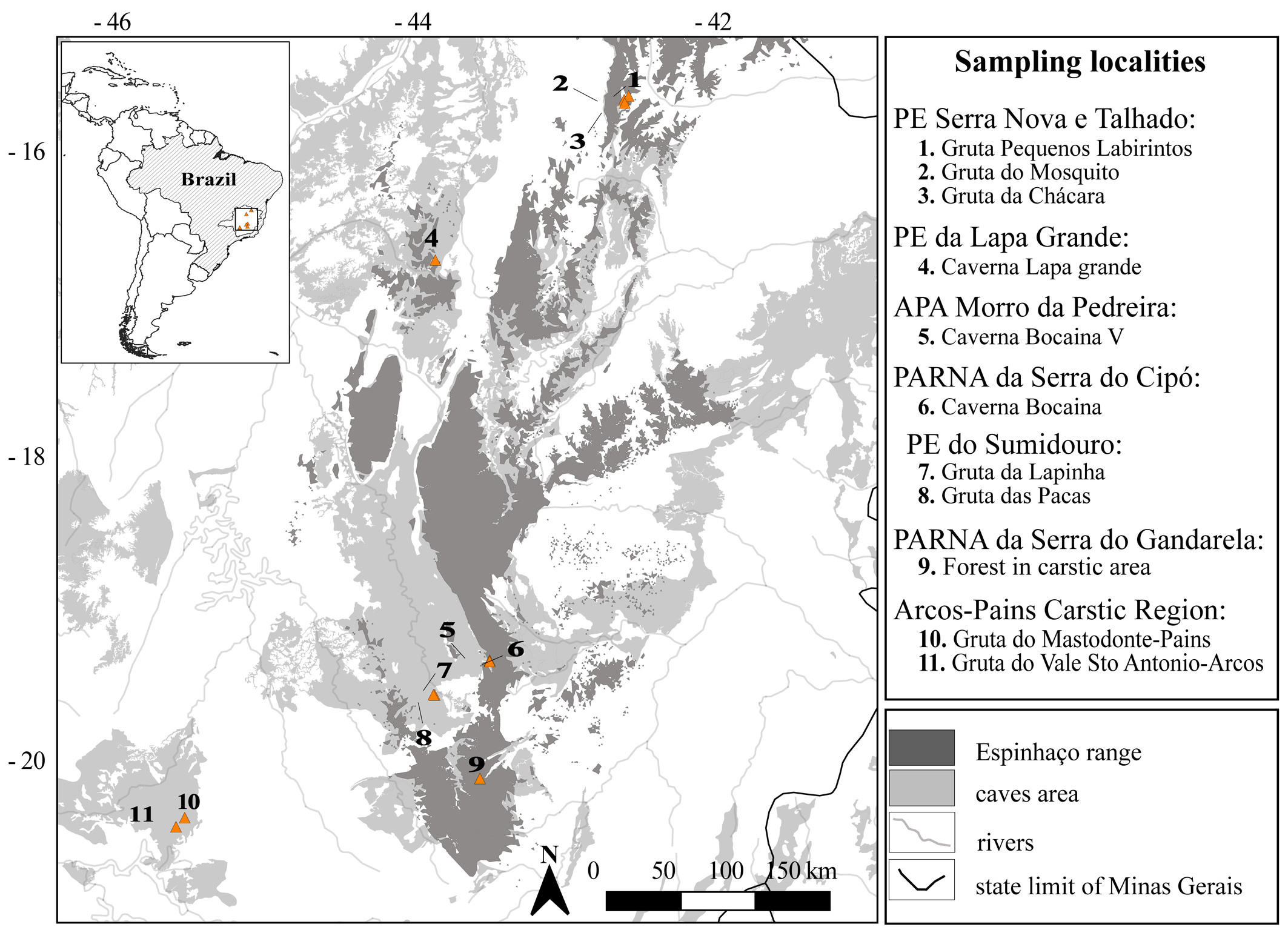

We examined a total of 81 specimens, consisting of males, females and nymphs from Minas Gerais state, Brazil. Of these, seventy-one individuals of Periglischrus had the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene successfully sequenced. Collection Numbers, BOLD IDs, BOLD Bin, instar/sex, host details, locality, coordinates and GenBank accession numbers are provided in Table 1. Localities are summarized in the map at Figure 1.

Mites were removed from their live bat hosts in the field by careful examination of these animals, using fine pincers and alcohol-soaked brushes, and immediately preserved in 96% ethanol, refrigerated in the field, and stored at -20 °C upon arrival. Bats were collected under ICMBio license SISBIO 71120–4, authorized by the Instituto Estadual de Florestas do Estado de Minas Gerais (IEF 009/2020), in accordance with the precepts of the ethics committee for animal use in research ''Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais (CEUA)'' of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), protocol number 50/2020. Access to the genetic heritage from Brazilian mites was registered in SisGen (register number: A054674).

DNA extraction, mounting, mites ID, photo-vouchers and collection

Genomic DNA was extracted from single specimens using Chelex based solution Instagene® (BIORAD) incubated for 30 min at 54 °C, followed by 8 min at 100 °C. The solution was spun and approximately 170 μL of supernatant was obtained for PCR reactions. Exoskeletons recovered from extraction were mounted on permanent microscope slides using Hoyer's medium (Walter and Krantz 2009) for morphology examination and kept as voucher material.

Identification and photo-documentation of vouchers were performed using a Leica DM 750 optical microscope with an ICC50 W digital camera attached. Besides, mites identification followed the keys proposed by Herrin and Tipton (1975) and Morales-Malacara (2001), supplemented by original description and re-descriptions, such as Furman (1966), Machado-Allison (1964, 1965a,1965b), Machado-Allison and Antequera (1971), Morales-Malacara et al. (2018), Rudnick (1960), Almeida et al. (2018). The nomenclature for idiosomal chaetotaxy follows Evans (1968) and Domrow (1972), leg chaetotaxy follows Evans (1963). All measurements are in micrometers.

The voucher materials are deposited at the Acarological Collection, Centro de Coleções Taxonômicas, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte City. Collection acronym: UFMG AC. The map was prepared using QGIS 3.22.1 (https://www.qgis.org/ko/site/ ![]() ).

).

PCR, sequencing and chromatogram checking

The amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) fragment of ~1200 bp was conducted using the primers and protocols described by Klimov et al. (2018). Amplifications were performed in 20 μL of final volume, with Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) in a Mastercycler nexus (Eppendorf) thermocycler. The master mix for initial PCR contained 2.0 μL of PCR buffer (1X), 1.4 μL MgCl 2 (50 mM), 1.4 μL of dNTP (10 mM each) and 0.8 μL of each oligonucleotide primer (10uM), to which 7–10 μL of genomic DNA was added or alternatively 0.5 μL of parent PCR products. All PCR products found positive in 1% agarose gel electrophoresis were purified using the Ampure® (Agencourt) kit and sequenced using a 3730 DNA Analyzer and BigDyeTM Terminator v3.1 (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol, employing M13 forward and reverse primers.

Forward and reverse chromatograms were checked, edited and assembled into contigs using software ChromasPro 1.41 (Technelysium Pty Ltd). All sequences generated for this study were compared with available mites sequences using the BLAST feature (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi ![]() ) (Altschul et al. 1997) and deposited in GenBank database (Table 1).

) (Altschul et al. 1997) and deposited in GenBank database (Table 1).

Alignment and phylogenetic inference

After preliminary automatic alignment with the aid of the MUSCLE software (Edgar 2004) sequences had their extremities trimmed and checked for the maintenance of the reading frame in the program MEGA 7.0 (Kumar et al. 2016). All sequences were uploaded into BOLD (Project-SPIN: DNA barcode library for Spinturnicidae mites from Brazil) database that assigned Barcode Index Number (BIN) (Ratnasingham and Hebert 2013). Pairwise mean interspecific and intraspecific p-distances values were calculated in MEGA 7.0. Haplotypes were identified employing DnaSP V. 6. and the alignment filtered from redundant sequences. The best-fitting models of nucleotide substitutions were found in ModelFinder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al. 2017) using Bayesian information criterion (BIC) as implemented in IQTree (Nguyen et al. 2015). This algorithm tests best fit models for each partition and the best partitioning scheme. The partitions taken into account were codon positions (1st, 2nd and 3rd).

Maximum likelihood (ML) tree was obtained in IQTree, with support being estimated using UltraFast Bootstrap (UFBoot) and SH-like approximate likelihood ratio test (SH-aLRT) was calculated in IQTree with 1,000 replicates. The bayesian inference (BI) was run on Beast v. 2.4.6 (Bouckaert et al. 2014). The analyses were run for 3x10⁸ generations, sampled every 3x10⁴ generations, under the Yule tree model. Convergence check using Tracer v.1.6.0 (Rambaut et al. 2014). The resulting trees are summarized using the software TreeAnnotator v1.8.4 (Drummond et al. 2012), with a 10% burnin, on the maximum clade credibility tree displaying the median heights for the tree nodes. Leading to an ultrametric bayesian tree.

Finally, two methods of putative species delimitation were performed: the Bayesian implementation of the Generalized Mixed Yule Coalescent algorithm (bGMYC) model (Reid and Carstens 2012) was used to delimit putative species belonging to different haplotypes following Costa et al. (2019) and Gomes-Almeida et al. (2023); and Assemble Species by Automatic Partitioning (ASAP) analysis (Puillandre et al. 2021), based on genetic distance calculated between DNA sequences and ranked by their ASAP-scores, was performed without the outgroup, with default settings and Kimura K80 substitution model (ts/tv=2.0) through the web-server accessible at via the webserver (https://bioinfo.mnhn.fr/abi/public/asap/asapweb.html ![]() ), using fasta files for locus COI as input file.

), using fasta files for locus COI as input file.

Results

Molecular analyses

We obtained 71 COI sequences of Periglischrus mite specimens morphologically assigned to six species, collected from 11 species of bats from Minas Gerais state. Sequences ranged from 657 to 953bp due to poor chromatogram quality due to repeated bases or mixed trace signals (multiple peaks) on their extremities. Among the 71 sequences, trimmed to 654 bp, 61 different haplotypes were identified. Intraspecific mean p-distances among sequences varied from 0.0006 (0.06%) in P. herrerai (n= 5) to 0.0322 (3.22%) in P. torrealbai (n= 6), among Periglischrus species, interspecific p-distances varied from 0.1255 (12.55%, P. herrerai x P. caligus) and 0.1833 (18.33%, P. caligus x P. acutisternus). Pairwise mean intraspecific and interspecific p-distances are summarized in Table 2.

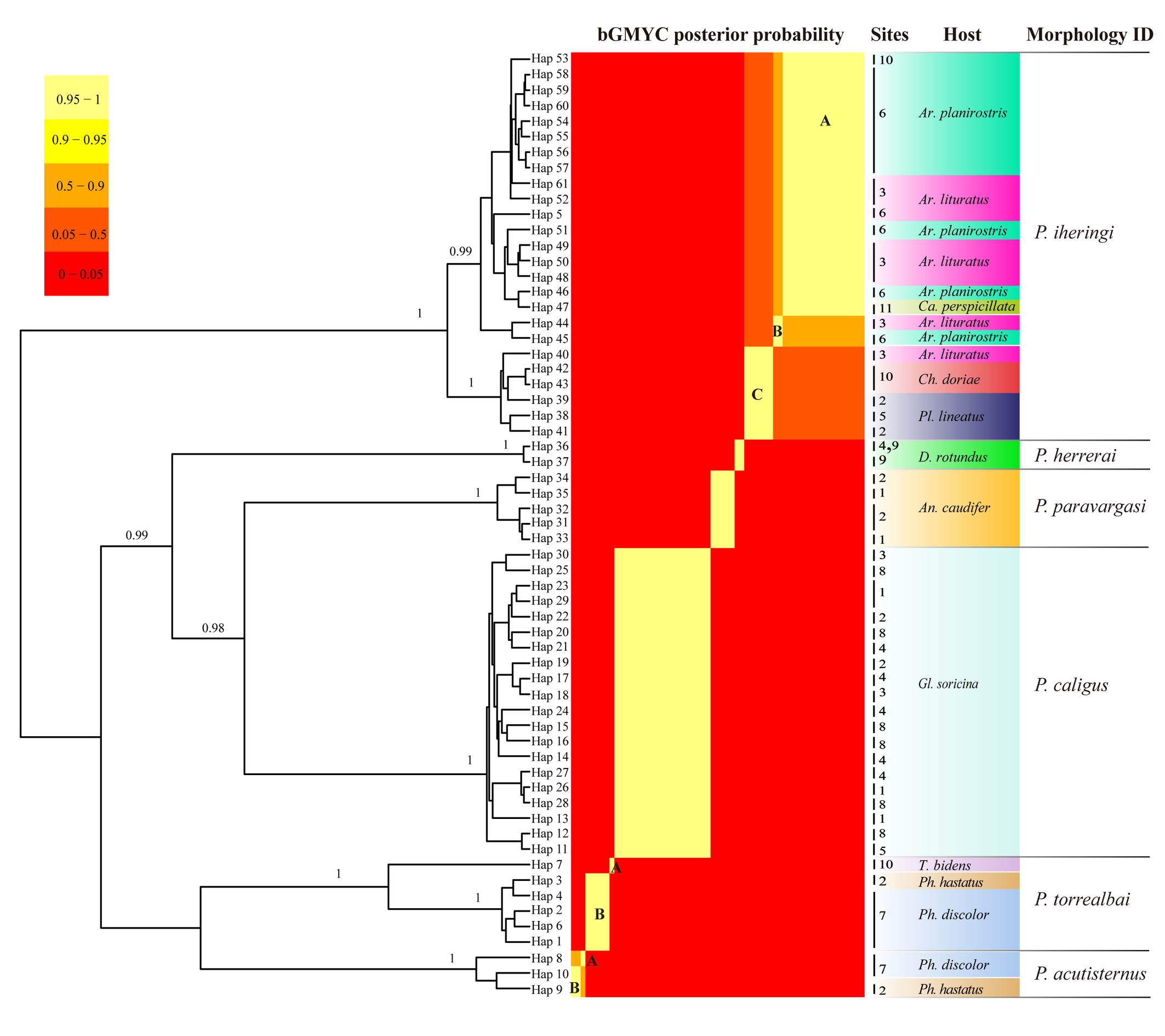

ModelFinder chose as best partition/model according to Bayesian information criterion (BIC) the first, second and third codon positions merged in a single partition under the model TIM+F+I+G4. Bayesian Inference and Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic inference resulted in six groups of Periglischrus species with clades that are highly supported, corroborating the previous morphological identification of the mites (Table 3; Figure 2; Supplementary figure 1-2). Eight BINs were identified by BOLD, five created from our data and three that matched existing BINs (Supplementary Figure 3). For bGMYC analyses, identified 10 species, with posterior probability being p < 0.95 (Figure 2), while the best partition provided by ASAP identified six hypothetical species that match six morphological species delimitations, observed a barcode gap of about 8-14% at the threshold distance of 10.57% (K80; 2.0) which has the best ASAP-score (1.50) within the available molecular data (Supplementary figure 3).

Below, we provide an annotated list reporting the six species of Periglischrus mites found, along with information on their distribution, host, COX1 barcode sequence data, and high-resolution photographs of diagnostic characters. All localities in Minas Gerais state, Brazil. Coordinates are given in WGS-84 format.

Taxonomy

Family Spinturnicidae Oudemans, 1902

Genus Periglischrus Kolenati, 1857

Periglischrus acutisternus Machado-Allison (Figures 3–5)

Periglischrus acutisternus Machado-Allison, 1964: 200–202 (original designation).

Periglischrus tiptoni Furman, 1966: 144–147.

Specimens examined — 2♀ (UFMG AC 220038, 220055) on bats Phyllostomus discolor (Wagner, 1843) (2 ex.) and 2♂ (UFMG AC 221025-26) on P. discolor (1 ex.): Lagoa Santa, Lapinha cave, PE Sumidouro, -19.5616° S, -43.959° E, 11 Aug. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964374 [UFMG AC 220038], OP964375 [UFMG AC 220055]). 1♀ (UFMG AC 220820), 1♂ (UFMG AC 220819) and 1 protonymph (UFMG AC 220136) on Phyllostomus hastatus (Pallas, 1767) (1 ex.): Rio Pardo de Minas, Mosquito cave (unregistered), PE Serra Nova e Talhado, -15.6545° S, -42.7335° E, 16 Dec. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964373 [UFMG AC 220136]).

Barcode sequences — OP964373 and OP964375 (Table 1).

Distribution — Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Trinidad and Venezuela (Gettinger 2018; Beron 2020).

Hosts and records from Brazil — Mimon bennettii (Gray, 1838): Rio de Janeiro (Almeida et al. 2011); Phyllostomus discolor Wagner, 1843: Pernambuco (Dantas-Torres et al. 2009), Distrito Federal (Gettinger and Gribel 1989), Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017), Minas Gerais (present study); Phyllostomus hastatus (Pallas, 1767): Maranhão, Paraná and São Paulo (Confalonieri 1976), Minas Gerais (Confalonieri 1976 and present study), Rio de Janeiro (Lourenço et al. 2016); Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva et al. 2017).

Differential diagnosis — Female: large, idiosoma length less than 2.000 μm (n=3, 1.167–1.352, 1.279) (Figure 3A); dorsal opisthonotal area with four pairs of minute setae (Figure 3D); sternal plate has a flask-shaped with a narrow, subtriangular, median sclerotized projection at the anterior end of the plate (Figure 3E–F); distal posteroventral (pv) setae on tibia–tarsus I, genu–tarsus II and distal anteroventral (av) seta on genu-tibia II and tibia III are short, blunt and peg-like; and posteroventral (pv) setae of femur and genu I-II robust with finely serrated on entire surface (Figure 3H and K). Male: Smaller than female (n=3, 492–558, 518); has distinctly longer sternogenital (St1–St4) setae, extending almost to level of second pair of setae and second–fourth pairs of sternal setae extending beyond bases of adjacent posterior setae (Figure 4C); seven pairs of setae on intercoxal IV and one pair of minute setae posterior to sternogenital plate; ventral setae on legs I-II mostly normal, setiform, and slender, however, some may be enlarged, spinelike (Figure 4D–F); large dorsal setae of tarsi III–IV coarsely barbed or serrated (Figure 4K and N); proximal anterodorsal (ad) seta of femur–tibia I and genu IV medium to large in size (Machado-Allison 1964; Furman 1966; Herrin and Tipton 1975; Morales-Malacara 2001).

Nymphs: similar to males with regard to above features, except by ontogenetic differences: Protonymph is smaller and less sclerotized than deutonymphs and adults; peritreme is short, over coxa III; four pairs of proteronotal setae, usually lack Pn5 seta; sternal shield plate not completely developed and lacks St4 and genital seta; anal-intercoxal plate not completely developed but smaller than in deutonymphs and male; intercoxal IV area with five pairs of setae, including adanal pair. Deutonymph female and male are smaller and less sclerotized than adults; peritreme with a long and narrow extension anteriorly; pair of proteronotal setae as adults; sternal shield plate not completely developed but St4 and genital setae are present and off shield; anal-intercoxal plate not completely developed but smaller than in male (Deunff et al. 2011).

Remarks — This species is stenoxenous on bats of the genus Phyllostomus (Herrin and Tipton 1975), found here on bats Ph. discolor and Ph. hastatus. The record on Ph. discolor from Minas Gerais state is new to science. Individuals obtained in this study match the original description and re-descriptions (Machado-Allison 1964; Herrin and Tipton 1975; Furman 1966). This species often co-occurs with smaller P. torrealbai Machado-Allison, 1965a, males and nymphs of which may be misidentified as P. acutisternus due to the similar size, presence of some distinctly enlarged ventral setae of legs I and II, large dorsal setae of tarsi III–IV coarsely barbed or serrated; males with long sternogenital setae and intercoxal IV area bearing seven pairs of setae. P. acutisternus, however, has some ventral setae on legs I and II spinelike (instead of blunt and fusiform) and proximal anterodorsal (ad) seta of femur–tibia I and genu IV medium to large in size (instead of always small) (Herrin and Tipton 1975).

In our bGMYC species delimitation analyses (Figure 2) P. acutisternus is represented by three haplotypes (8, 9 and 10) out of three sequences. Haplotypes 9 and 10 were recovered as a single species with large posterior probability (pp. \textgreater95%), whereas haplotype 8 was associated with a lower posterior probability (pp. 76%).

Periglischrus caligus Kolenati (Figures 6–8)

Periglischrus caligus Kolenati, 1857: 60 (original designation).

Periglischrus setosus Machado-Allison 1964: 199–200.

Specimens examined — 2♀ (UFMG AC 220058, 221031), 2♂ (UFMG AC 220066, 221035) and 3 protonymphs (UFMG AC 220057, 220059–60) on bat Glossophaga soricina (4 ex.): Lagoa Santa, Pacas cave, PE Sumidouro, -19.5606° S, -43.9667° E, 12 Aug. 2021, collected by B. Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964376 [UFMG AC 220066], OP964377 [UFMG AC 221035], OP964379[UFMG AC 221031], OP964395[UFMG AC 220060], OP964396[UFMG AC 220059], OP964397[UFMG AC 220058], OP964398[UFMG AC 220057]); 4♂ (UFMG AC 220107–09, 220808) and 2 protonymphs (UFMG AC 220124, 221032) on Glossophaga soricina (3 ex.): Montes Claros, Lapa Grande cave, PE da Lapa Grande, -16.7067° S, -43.9549° E, 13-14 Dec. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence[voucher code]: OP964378[UFMG AC 221032], OP964381[UFMG AC 220808], OP964390[UFMG AC 220124], OP964391[UFMG AC 220109], OP964392[UFMG AC 220108], OP964393[UFMG AC 220107]); 2♀(UFMG AC 220214, 220218), 1♂ (UFMG AC 221016) and 1 protonymph (UFMG AC 220216) on Glossophaga soricina (2 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Rio Pardo de Minas, Chácara cave (unregistered), PE Serra Nova e Talhado, -15.6758° S, -42.7295° E, 20 Dec. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence[voucher code]: OP964380[UFMG AC 221016], OP964382[UFMG AC 220216], OP964383[UFMG AC 220214]); 2♀(UFMG AC 220147, 220149) and 1♂ (UFMG AC 220148) on Glossophaga soricina (1 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Rio Pardo de Minas, Mosquito cave (unregistered), PE Serra Nova e Talhado, -15.6545° S, -42.7335° E, 16 Dec. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence[voucher code]: OP964388 [UFMG AC 220148] and OP964389[UFMG AC 220147]); 2♀(UFMG AC 220186, 220181), 1♂ (UFMG AC 220185) and 2 protonymphs (UFMG AC 220183-84) on Glossophaga soricina (2 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Rio Pardo de Minas, Pequenos Labirintos cave (unregistered), PE Serra Nova e Talhado, -15.6293° S, -42.7043° E, 18 Dec. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence[voucher code]: OP964384–87); 1♂(UFMG AC 220104) on Glossophaga soricina (1 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Santana do Riacho, Bocaina V cave, APA Morro da Pedreira, -19.3346° S, -43.6032° E, 17 Sep. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence[voucher code]: OP964394 [UFMG AC 220104]).

Barcode sequences — OP964376–78, OP964381, OP964383–92, OP964394, OP964397 (Table 1).

Distribution — Bolivia, Brazil, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Suriname, Venezuela (Beron 2020).

Hosts and records from Brazil — Artibeus lituratus (Olfers, 1818): Rio de Janeiro (Lourenço et al. 2020); Artibeus planirostris: Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017); Glossophaga soricina (Pallas, 1766): Ceará, Mato Grosso (Almeida et al. 2016b), Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo (Confalonieri 1976), Distrito Federal (Gettinger and Gribel 1989), Brazil (Rudnick 1960), Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017), Rio Grande do Sul (Silva et al. 2009) and Minas Gerais (new report in present study); Platyrrhinus lineatus: Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013); unknown bat: Mato Grosso (Confalonieri 1976).

Differential diagnosis — Female: four pairs of small to minute setae on dorsal opistonothal area (Figure 6D); sternal plates subpentagonal, narrow anterior border with anterior projection narrowly rounded (Figure 6E–F); posterolateral (pl) setae on femur-tibia IV greatly inflated, with slender recurved end (Figure 6M–N). Male: sternogenital seta St1 small, extending posteriorly about two-thirds the distance to first pair of pores; intercoxal IV area bears eight pairs of setae with first pair as microsetae posterior to sternogenital plate (Figure 7C); coxa II with seta pv much shorter than the width of coxa II (Figure 7I) (Herrin and Tipton 1975; Morales-Malacara 2001; Morales-Malacara and López-Ortega 2001). Protonymph: similar to males, except by ontogenetic differences (Deunff et al. 2011) (Figures 8A–N).

Remarks — P. caligus is reported for the first time to Minas Gerais fauna. This is a stenoxenous species on glossophagine bats of the genus Glossophaga. Morphological characters of examined specimens agree with original description and re-descriptions (Machado-Allison 1964; Herrin and Tipton 1975; Furman 1966). Periglischrus caligus protonymph may be misidentified as P. herrerai that differs by having first pair of setae on intercoxal area IV small (minute in P. caligus, Figures 8C and 10C); tarsus III with proximal posterodorsal (pd) seta medium to small (vs. large) and proximal anterodorsal (ad) seta similar in size with pd (vs. small, Figure 8K and 10K); Proximal anterodorsal (ad) on femur IV medium (vs. small, Figure 8L and 10L) and proximal antero and posterodorsal setae on genu IV medium (vs. small, Figure 8M and 10M).

In our bGMYC species delimitation analyses (Fig. 2) Periglischrus caligus is represented by 20 haplotypes (11 to 30) out of 23 sequences and all haplotypes were recovered as a single putative species with pp. > 95%.

Periglischrus herrerai Machado-Allison (Figures 9–10)

Periglischrus herrerai Machado-Allison, 1965a:282–284 (original designation).

Periglischrus desmodi Furman, 1966: 139–141.

Periglischrus herrerai, Herrin & Tipton, 1975:55.

Periglischrus herrerai, Morales-Malacara et al., 2018: 300–316.

Specimens examined — 1♂ (UFMG AC 221059), 1 deutonymph ♀ (UFMG AC 221061) and 1 deutonymph ♂ (UFMG AC 221060) on Desmodus rotundus (1 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Rio Acima, carste/mata, PN Serra do Gandarela, -20.1105, -43.6661° E, 27 Mar. 2020, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964399 [UFMG AC 221059], OP964400[UFMG AC 221060] and OP964401[UFMG AC 221061]); 2 protonymphs (UFMG AC 220113–14) on Desmodus rotundus (1 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Montes Claros, Lapa Grande cave, PE da Lapa Grande, -16.7067° S, -43.9549° E, 13-14 Dec. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964402 [UFMG AC 220114] and OP964403 [UFMG AC 220113]).

Barcode sequences — OP964399–403 (Table 1).

Distribution — Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Trinidad, Venezuela (Gettinger 2018; Beron 2020).

Hosts and records from Brazil — Artibeus planirostris: Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017); Desmodus rotundus (E. Geoffroy, 1810): Distrito Federal (Gettinger and Gribel 1989), Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017), Minas Gerais (new report in present study), Rio de Janeiro (Confalonieri 1976; Almeida et al. 2011), São Paulo (Confalonieri 1976); Myotis nigricans: Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013); Sturnira lilium: Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017).

Differential diagnosis — Female: distance between first and second pairs of dorsal proteronotal setae less than or equal to distance between second and third pairs; six opistonothal setae short to very short (first pair just posterior to coxa IV largest). Sternal plate subpentagonal in shape, with narrow anterior border, and an acute small and triangular tip (homomorphic), or with sternal plate with subpentagonal shape gradually distorted to a spade-shaped outline with a broad arrow head pointed tip (maximum heteromorphic form); proximal anterodorsal seta of tibia II large (Morales-Malacara et al. 2018). Male: narrow longitudinal and cross-shaped unsclerotized crack in the center of dorsal plate (Morales-Malacara 2001; Morales-Malacara et al. 2018) (Figure 9B); intercoxa IV area with nine pairs of setae, plus one pair of adanal setae: first pair small to medium sized and situated posterior to sternogenital plate (Herrin and Tipton 1975) with a unique reticulated sclerotized pattern over most of plate (Figure 9C) (Morales-Malacara 2001; Morales-Malacara et al. 2018).

Nymphs (Figure 10A–N): similar to males with regard to above features, except by ontogenetic differences (Deunff et al. 2011). Deutonymph female has 13 pairs setae on intercoxal IV area, including adanal pair, and seven pairs of hysteronotal setae (one pair poststigmal setae and six pairs opisthosomal setae) and plus one unpaired seta on caudal dorsum. Deutonymph male has 10 pairs setae on intercoxal IV area, including adanal pair, and five pairs hysteronotal setae (one pair poststigmal setae and four pair opisthosomal setae) and plus one unpaired seta on caudal dorsum (similar to adult male). Protonymph has only two pairs hysteronotal setae (one pair poststigmal setae and one pair opisthosomal setae) and plus one unpaired seta on caudal dorsum.

Remarks — P. herrerai is reported for the first time from Minas Gerais. This species is monoxenous associated with the vampire bat, D. rotundus. Morphological characters of examined specimens match those of the original description and re-descriptions (Machado-Allison 1965a; Furman 1966; Herrin and Tipton 1975; Morales-Malacara et al. 2018), except by four pairs of dorsal opisthosomal setae on male deutonymph, instead of three pairs.

In our bGMYC species delimitation analyses (Figure 2), both Periglischrus herrerai haplotypes (haplotypes 36 and 37) out of five sequences recovered as a single putative species with pp. \textgreater95%.

Periglischrus iheringi Oudemans (Figures 11–13)

Periglischrus iheringi Oudemans, 1902: 38.

Periglischrus jheringi (sic) Oudemans, 1903:135.

Periglischrus meridensis Hirst, 1927: 335.

Spinturnix ewingia Wharton, 1938: 139.

Spinturnix artibiensis Radford, 1951: 97.

Specimens examined — Male (UFMG AC 221127) on Carollia perspicillata (1 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Arcos, Vale Sto Antônio cave, -20.3673, -45.5756° E, 26 jan. 2021, collected by A. Tahara et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964413[UFMG AC 221127]); deutonymph female (UFMG AC 220098) on Artibeus lituratus (PNSC0092): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Santana do Riacho, Bocaina cave, PN da Serra do Cipó, -19.3419° S, -43.6032° E, 19 Sep. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence[voucher code]: OP964421[UFMG AC 220098]); female (UFMG AC 221115), male (UFMG AC 221114) on Chiroderma doriae (1 ex.) and male (UFMG AC 221113) on Artibeus planirostris (1 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Pains, Mastodonte cave, -20.4270, -45.6322° E, 03 Mar. 2020, collected by A. Tahara et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964414[UFMG AC 221115], OP964420[UFMG AC 221113] and OP964432[UFMG AC 221114]); 2♀(UFMG AC 221011-12), 4♂ (UFMG AC 220221, 220224, 220226, 221013), 2 deutonymph♂ (UFMG AC 220227, 220230) and 2 protonymphs (UFMG AC 221014–15) on Artibeus lituratus (3 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Rio Pardo de Minas, Chácara cave (unregistered), PE Serra Nova e Talhado, -15.6758° S, -42.7295° E, 20 Dec. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964404[UFMG AC 220221], OP964416[UFMG AC 220230], OP964417[UFMG AC 220227], OP964418[UFMG AC 220226], OP964419[UFMG AC 220224], OP964427[UFMG AC 221015], OP964428[UFMG AC 221014], OP964429[UFMG AC 221013], OP964430[UFMG AC 221012], OP964431[UFMG AC 221011]); 1 ♀(UFMG AC 220157) and 1 protonymph (UFMG AC 220828) on Platyrrhinus lineatus (1 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Rio Pardo de Minas, Mosquito cave (unregistered), PE Serra Nova e Talhado, -15.6545° S, -42.7335° E, 16 Dec. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964411[UFMG AC 220157], OP964415[UFMG AC 220157]); 1♀ (UFMG AC 220092), 4♂ (UFMG AC 220090, 220093, 220095, 221021), 2 deutonymph ♀ (UFMG AC 221020, 221022), deutonymph ♂(UFMG AC 221018), 3 protonymphs (UFMG AC 220091, 220094, 221017) on Artibeus planirostris (4 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Santana do Riacho, Bocaina cave, PN da Serra do Cipó, -19.3419° S, -43.6032, 19 Sep. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964405, [UFMG AC 220095], OP964406[UFMG AC 220094], OP964407[UFMG AC 220093], OP964408[UFMG AC 220092], OP964409[UFMG AC 220091], OP964410[UFMG AC 220090], OP964422[UFMG AC 221022], OP964423[UFMG AC 221021], OP964424[UFMG AC 221020], OP964425[UFMG AC 221018], OP964426[UFMG AC 221017]); 1 protonymph (UFMG AC 220085) on Platyrrhinus lineatus (1 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Santana do Riacho, Bocaina V cave, APA Morro da Pedreira, -19.3346° S, -43.6032° E, 17 Sep. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964412[UFMG AC 220085]).

Barcode sequences — OP964404–08, OP964412–19, OP964421, OP964423–29 (Table 1).

Distribution — Bolivia, Brazil (detailed below), Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Surinam, Trinidad, Venezuela and Virgin Islands (Gettinger 2018; Beron 2020).

Hosts and records from Brazil — Anoura caudifer (É. Geoffroy, 1818): Rio Grande do Sul (Silva et al. 2009); Anoura sp.: Rio Grande do Sul (Silva et al. 2009); Artibeus fimbriatus: Rio de Janeiro (Lourenço et al. 2016, 2020); Rio Grande do Sul (Silva et al. 2009); Artibeus lituratus (Olfers, 1818): Ceará, Mato Grosso (Almeida et al. 2016b), Distrito Federal (Gettinger and Gribel 1989), Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017), Minas Gerais (Azevedo et al. 2002; present study), Paraná and São Paulo (Confalonieri 1976), Pernambuco (Dantas-Torres et al. 2009), Rio de Janeiro (Confalonieri 1976; Almeida et al. 2010, 2011; Almeida et al. 2015; Lourenço et al. 2016), Rio Grande do Sul (Silva et al. 2009), Santa Catarina (Rudnick 1960), Sergipe (Bezerra and Bocchiglieri 2018), Brazil (Webb and Loomis 1977); Artibeus obscurus: Rio de Janeiro (Almeida et al. 2011; Lourenço et al. 2016); Artibeus planirostris: Ceará (Almeida et al. 2016b; Confalonieri 1976); Distrito Federal (Gettinger and Gribel 1989); Mato Grosso (Almeida et al. 2016b); Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017); Minas Gerais (present study), Pernambuco (Dantas-Torres et al. 2009); Rio de Janeiro (Almeida et al. 2011; Confalonieri 1976; Lourenço et al. 2016) and Sergipe (Bezerra and Bocchiglieri 2018); Carollia perspicillata: Ceará (Almeida et al. 2016b; Confalonieri 1976), Minas Gerais (present study), Rio de Janeiro (Almeida et al. 2011; Lourenço et al. 2020); Chiroderma doriae: Rio de janeiro (Lourenço et al. 2016), Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva et al. 2017), Minas Gerais (present study); Chiroderma vizottoi: Ceará (Almeida et al. 2016b); Chrotopterus auritus: São Paulo (Confalonieri 1976); Dermanura cinerea (Gervais, 1856): Distrito Federal (Gettinger and Gribel 1989), Sergipe (Bezerra and Bocchiglieri 2018); Desmodus rotundus (E. Geoffroy, 1810): Rio de janeiro (Lourenço et al. 2016), São Paulo (Confalonieri 1976); Eptesicus brasiliensis (Desmarest, 1819): Pará (Confalonieri 1976); Glossophaga soricina (Pallas, 1766): Rio de Janeiro (Lourenço et al. 2020), Rio Grande do Sul (Silva et al. 2009); Lophostoma brasiliense: Sergipe (Bezerra and Bocchiglieri 2018); Lophostoma silviculum: Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva et al. 2017); Micronycteris microtis (Miller, 1898): Rio de Janeiro (Lourenço et al. 2020); Myotis nigricans: Rio de Janeiro (Almeida et al. 2010); Noctilio albiventris: Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017); Peropteryx macrotis: Ceará (Confalonieri 1976); Phyllostomus discolor: Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017), Sergipe (Bezerra and Bocchiglieri, 2018); Platyrrhinus incarum (Thomas, 1912): Mato Grosso (Almeida et al. 2016b); Platyrrhinus lineatus (E. Geoffroy, 1810): Ceará (Almeida et al. 2016b), Distrito Federal (Gettinger and Gribel 1989), Mato Grosso (Almeida et al. 2016b), Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017), Minas Gerais (present study), Pernambuco (Dantas-Torres et al. 2009), Rio de Janeiro (Confalonieri 1976; Lourenço et al. 2016), São Paulo (Oudemans 1902); Platyrrhinus recifinus (Thomas, 1901): Rio de Janeiro (Lourenço et al. 2016, 2020); Platyrrhinus sp.: Rio de Janeiro (Confalonieri 1976); Pygoderma bilabiatum: Rio de Janeiro (Lourenço et al. 2016); Sturnira lilium (E. Geoffroy, 1810): Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017), Minas Gerais (Azevedo et al. 2002), Pernambuco (Dantas-Torres et al. 2009), Rio de Janeiro (Almeida et al. 2011; Confalonieri 1976; Lourenço et al. 2016); Sturnira tildae: Espírito Santo (Confalonieri 1976); Tonatia silvicola (d'Orbigny, 1836): Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013); Vampyressa pusilla (Wagner, 1843): Rio de janeiro (Lourenço et al. 2016, 2020), Vampyrodes caraccioli (Thomas, 1889): Pará (Confalonieri 1976).

Differential diagnosis — Females: first pair of dorsal proteronotal setae minute and on the anterolateral margin of the dorsal plate, while the other proteronotal setae large and off the plate (Figure 11C); sternal plate pear shaped (Figure 11E–F); proximal anterodorsal seta of femur II minute and proximal posterodorsal seta of femur II medium sized (Figure 11J); posteroventral (pv) seta of femur-tibia IV straight and bladelike (Figure 11M–N). Male: intercoxa IV area with eight pairs of setae, first pair of setae posterior to sternal plate short to minute; sternogenital setae long, first pair extending to or beyond level of second pair of setae (Figure 12C); proximal antero- and posterodorsal setae of femur IV long, subequal in length (Figure 12L) (Herrin and Tipton 1975). Nymphs: similar to males with regard to above features, except by ontogenetic differences (Deunff et al. 2011) (Figure 13A–N). Deutonymph female has 13 pairs setae on intercoxal IV area, including adanal pair, and five pairs of hysteronotal setae (one pair poststigmal setae and four pairs opisthosomal setae) and plus one unpaired seta on caudal dorsum. Deutonymph male has eight pairs setae on intercoxal IV area, including adanal pair, two pairs hysteronotal setae (one pair poststigmal setae and one pair opisthosomal setae) and plus one unpaired seta on caudal dorsum (similar to adult male). Protonymph has pairs of hysteronotal setae and caudal dorsum similar to deutonymph male.

Remarks — This is the first record of P. iheringi on bats Ar. planirostris, Ca. perspicillata, Ch. doriae and Pl. lineatus from Minas Gerais. The species is oligoxenous, associated with numerous phyllostomid bats, especially with Sternodermatini bats (Herrin and Tipton 1975), and closely related to P. ojastii Machado-Allison, 1964. They share pronounced shoulders on the anterolateral outline of the dorsal plate and similarly shaped sternal and sternogenital plates, and posteroventral setae of femur-tibia IV are straight and bladelike in females (Herrin and Tipton 1975; Morales-Malacara 2001). They may be distinguished by the presence of a small central pair of foveae in P. iheringi associated with a longitudinal medial keel, the end of which is joined with the anterocentral unpaired fovea, such that it looks like an arrow (vs. absent in P. ojastii), Pnl are very small (vs. Pnl-Pn5). In both sexes distance between the first and second pairs is distinctly greater than that between the second and third (vs. P. ojastii the distance between the first and second pairs of podosomal setae is distinctly less than the distance between the second and third pairs). Morphological characters of examined specimens match original description and re-descriptions (Rudnick 1960; Herrin and Tipton 1975; Furman 1966).

In our bGMYC species delimitation analyses (Figure 2), 25 haplotypes (5, 38 to 61) out of 29 sequences from individuals morphologically assigned to P. iheringi were recovered split into three well supported species (pp \textgreater95%). The first putative species hereinafter referred to as P. iheringi A includes haplotypes 5, 46 to 61 and the second, as P. iheringi B, includes haplotypes 44 to 45 and third, as P. iheringi C includes haplotypes 38 to 45.

On other hand, the posterior probability of including all mites identified morphologically as P. iheringi in a single species is less than 50%, suggesting P. iheringi as a species complex. Interesting, when we turn to hosts: P. iheringi A was found on Artibeus planirostris Artibeus lituratus and Carollia perspicillata; P. iheringi B was found on Artibeus planirostris and Art. lituratus; and P. iheringi C was found on Art. lituratus, Platyrrhinus lineatus and Chiroderma doriae. Hence, all clades of P. iheringi were found on Artibeus lituratus.

Periglischrus paravargasi Herrin & Tipton (Figures 14–16)

Periglischrus paravargasi Herrin & Tipton, 1975: 46.

Specimens examined — 1♂ (UFMG AC 221122) on Anoura caudifer (1 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Formiga, carste/mata of Gruta Paca, 26 Jan. 2021, collected by A. Tahara et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964435[UFMG AC 221122]); 2♀(UFMG AC 220162, 220813) and 1 protonymph (UFMG AC 220166) on A. caudifer (1 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Rio Pardo de Minas, Mosquito cave (unregistered), PE Serra Nova e Talhado, -15.6545° S, -42.7335° E, 16 Dec. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964434[UFMG AC 220162], OP964436[UFMG AC 220813], OP964438[UFMG AC 220166]); 2 deutonymphs ♀ (UFMG AC 220178, 221009) on A. caudifer (1 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Rio Pardo de Minas, Pequenos Labirintos cave (unregistered), PE Serra Nova e Talhado, -15.6293° S, -42.7043° E, 18 Dec. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964433[UFMG AC 220178], OP964437[UFMG AC 221009]).

Barcode sequences — OP964433–38 (Table 1).

Distribution — Brazil, French Guiana, Peru and Venezuela (Gettinger 2018; Beron 2020).

Hosts and records from Brazil — Anoura caudifer: Distrito Federal (Gettinger and Gribel 1989), Rio de janeiro (Lourenço et al. 2016) and Minas Gerais (this study).

Differential diagnosis — Female: dorsal plate distinctive ornamentation with numerous small darker circular areas, some larger irregularly shaped lighter areas, and very small circular pores or setal bases. (Figure 14C); dorsal opisthosoma with six pairs of setae, first pair behind level of coxa IV rather large; next three pairs medium sized; last two pairs (posteriomost) small to minute (Figure 14D); sternal plates subpentagonal, distinctly longer than wide, with longer anterior end border that narrows abruptly, forming narrow anterior projection (Figure 14E–F); posterolateral setae of femur to tibia IV greatly inflated, with slender recurved end (Figure 14M–N). Male: sternogenital setae are long, the setae St1 extending posterior to or slightly beyond the level of the first pair of pores; intercoxal IV area with seven pairs of setae plus one pairs of subterminal adanal setae; first pair posterior to sternogenital plate minute, and coxa II with setae pv long (length at least equal to the width of coxa II) (Herrin and Tipton 1975; Morales-Malacara 2001). Nymphs: similar to males with regard to above features, except by ontogenetic differences (Deunff et al. 2011) (Figure 16A–N). Deutonymph female has 13 pairs setae on intercoxal IV area, including adanal pair, and seven pairs of hysteronotal setae (one pair poststigmal setae and six pairs opisthosomal setae) and plus one unpaired seta on caudal dorsum. Protonymph has two pairs hysteronotal setae (one pair poststigmal setae and one pair opisthosomal setae) and plus one unpaired seta on caudal dorsum (similar to adult male).

Remarks — P. paravargasi is reported for the first time from Minas Gerais state. This species seems to be monoxenous, exclusive to Anoura caudifer. Examined specimens match those of the original description and re-descriptions (Herrin and Tipton 1975; Morales-Malacara 2001). In our bGMYC species delimitation analyses (Figure 2), Periglischrus paravargasi led to five haplotypes (31-35) out five sequences and was recovered as a single species with pp. \textgreater95%.

Periglischrus torrealbai Machado-Allison (Figures 17–19)

Periglischrus torrealbai Machado-Allison, 1965a:276–279.

Periglischrus inflatiseta Furman, 1966: 134–135.

Specimens examined — 2♂ (UFMG AC 220041, 221030) and 1 protonymph (UFMG AC 220054) on Phyllostomus discolor (3 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Lagoa Santa, Lapinha cave, PE Sumidouro, -19.5616° S, -43.959° E, 11 Aug. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence[voucher code]: OP964439[UFMG AC 221030], OP964442[UFMG AC 220041], OP964444[UFMG AC 220054]); 1♂ (UFMG AC 221129) on Tonatia bidens (1 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Pains, Mastodonte cave, -20.4270° S, -45.6322° E, 27 Jan. 2021, collected by A. Tahara et al. (COX1 sequence[voucher code]: OP964443[UFMG AC 221129]); 4♂ (UFMG AC 220137, 220138, 220823, 220139) on Phyllostomus hastatus (PESNT112): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Rio Pardo de Minas, Mosquito cave (unregistered), PE Serra Nova e Talhado, -15.6545° S, -42.7335° E, 16 Dec. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence[voucher code]: OP964440[UFMG AC 220139]); ♀(UFMG AC 220043) on Phyllostomus discolor (1 ex.): Brazil, Minas Gerais, Lagoa Santa, Lapinha cave, PE Sumidouro, -19.5616° S, -43.959° E, 11 Aug. 2021, collected by B. Gomes-Almeida et al. (COX1 sequence [voucher code]: OP964441[UFMG AC 220043]).

Barcode sequences — OP964441–44 (Table 1).

Distribution — Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, Peru and Venezuela (Gettinger 2018; Beron 2020).

Hosts and records from Brazil — Artibeus planirostris (Spix, 1823): Ceará (Almeida et al. 2016b); Lophostoma silviculum: Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017); Phyllostomus discolor (Wagner, 1843): Ceará (Almeida et al. 2016b; Almeida et al. 2018); Distrito Federal (Gettinger and Gribel 1989); Mato Grosso (Almeida et al. 2018); Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017), Minas Gerais (present study); Phyllostomus hastatus (Pallas, 1767): Minas Gerais and São Paulo (Confalonieri 1976); Mato Grosso (Almeida et al. 2018); Mato Grosso do Sul (Silva and Graciolli 2013; Silva et al. 2017); Rio de Janeiro (Almeida et al. 2011; Almeida et al. 2018; Lourenço et al. 2016; Lourenço et al. 2020); Tonatia bidens (Spix, 1823): Ceará (Almeida et al. 2016b; Almeida et al. 2018), Minas Gerais (present study).

Differential diagnosis — Female: small, idiosoma length up to 779 μm (Figure 17A); dorsal opisthosoma with 4-5 pairs of minute setae (Figure 17D); sternal plate broadly pear shaped; five pairs of ventral body setae (metasternal setae, genital setae, and three pairs of ventral opisthosomal setae posterior to the sternal plate) expanded basally but with acute tips (Figure 17E–F); certain ventral setae of legs I and II short and spinelike to peglike in both sexes. Ventral setae on trochanters I–II, femora I–II, genua II, and one posteroventral seta of each tarsi III short, enlarged and peglike. Setae pv on femur-genu IV inflated and bladelike rather than setiform and recurved. Male: sternogenital setae long, with first pair extending well beyond level of first pair of pores and the second through fourth sternogenital setae longer, extending beyond bases of adjacent posterior setae; some setae of ventral intercoxa IV area enlarged and expanded basally; many ventral setae of legs I and II distinctly enlarged, blunt and fusiform; large dorsal setae of tarsi III–IV coarsely barbed or serrated; proximal anterodorsal (ad) seta of femur–tibia I and genu IV always small. Nymphs: similar to males with regard to above features, except by ontogenetic differences (Deunff et al. 2011) (Figure 19A–N).

Remarks — This is the first record of P. torrealbai on bats Ph. discolor and T. bidens to Minas Gerais state. This is a stenoxenous species, associated with the phyllostomine bats Phyllostomus and Tonatia, and the smallest species associated with genus Phyllostomus Lacépède, 1799 (the other are P. acutisternus and P. grandisoma Herrin & Tipton, 1975) (Herrin and Tipton 1975; Almeida et al. 2018). Morphological characters match original description and re-descriptions (Machado-Allison 1965a; Furman 1966; Herrin and Tipton 1975; Almeida et al. 2018).

In our bGMYC species delimitation (Figure 2), Periglischrus torrealbai is represented by six haplotypes (1–4 and 6–7) out of six sequences and recovered as two putative species with pp. \textgreater95%: P. torrealbai A (7) from Tonatia bidens and P. torrealbai B (1 to 4 and 6) from Phyllostomus hastatus and Ph. discolor. This result is in part consistent with results of Almeida et al. (2018), who showed that P. torrealbai morphology varies on a morphometric basis among the host bat species P. discolor, P. hastatus and T. bidens with three morphologically distinct species with host specificity, and suggests that P. torrealbai includes at least two distinct species of Periglischrus, one with Phyllostomus and Tonatia genus.

Discussion

The sequenced COI fragment provided a confident range of \textgreater10% for interspecific divergence indicates that there is sufficient genetic differentiation among species to reliably distinguish them using this molecular marker. The maximum likelihood (ML) analysis showed consistency with morphological identification of Periglischrus species based on descriptions, redescriptions and taxonomic keys (Machado-Allison 1964, 1965a; Furman 1966; Herrin and Tipton 1975; Morales-Malcara 2001). The nodes were supported by high bootstrap values (100%) further strengthening the confidence in the accuracy of species identification based on DNA barcoding.

Species clustering and delimitation by BINs, ASAP and bGMYC yielded distinct but partially consistent results. For ASAP analysis identified a barcode gap and supported the six species, matching the morphological identification, while BINs supported eight species, as it subdivided P. acutisternus and P. torrealbai. In contrast, bGMYC identified at least 10 putative species, as it subdivided P. acutisternus and P. torrealbai into two species each (concordant with BINs), and further subdivided P. iheringi into three species.

The observed subdivisions within P. acutisternus, P. torrealbai, and particularly P. iheringi suggest that BINs and bGMYC oversplit these species, something previously observed (Gomes-Almeida et al. 2023). The co-occurrence of putative species in the same locations and even on the same host allows us to discard geographic barriers as a cause for the genetic structure observed today. Instead, the observed genetic structure may be explained by past vicariance events caused by host shifts and a recent re-encounter in the case of P. iheringi A, B and C sampled in the same host. Nevertheless, to test these hypotheses more specimens and genes, especially nuclear genes, must be analyzed.

On a positive note, genetic barcoding has proved to be a valuable and effective tool to unravel genetic diversity and aid in the identification of Periglischrus mite species. Moreover, this approach has enabled reliable identification of immature stages. Notably, our study reports Periglischrus caligus, P. herrerai and P. paravargasi for the first time from Minas Gerais, extending their distribution ranges.

Morphological character-based taxonomy

Herrin and Tipton (1975) assigned species to groups based mainly on sternal plate outline, size and location of the proteronotal setae, and size of proximal dorsal setae on femur I-IV. However, Morales-Malacara (2001) later added new morphological characters of the idiosoma to the type-based taxonomy of Periglischrus, and renamed and re-defined these species groups and subgroups. Herewith, the species recorded are classified in six species groups according to Morales-Malacara 2001.

Periglischrus acutisternus is a member of acutisternus species group, alongside with P. tonatii Herrin & Tipton, 1975, P. paracutisternus Machado-Allison & Antequera, 1971, P. dusbabeki Machado-Allison & Antequera, 1971, and P. steresotrichus Morales-Malacara & Juste, 2002 (Morales-Malacara and Juste 2002). They share female sternal plates with a distinct anterior median projection, subtriangular or elongated in shape, distinct constriction anterior to first sternal setae, and the anterolateral corners of sternogenital plate are weakly defined and long sternogenital setae (Morales-Malacara 2001). Herrin and Tipton (1975) called it subgroup B from Group I, and included P. grandisoma Herrin & Tipton, 1975 too. To them, the subgroup is based on the presence of a medium-sized to prominent mediodistal lobe on the palpal tibia in addition to above mentioned similarity in female sternal plate shape.

Periglischrus torrealbai belongs to the torrealbai species-group, that also comprises P. paratorrealbai Herrin & Tipton, 1975 and P. eurysternus Morales-Malacara & Juste, 2002. According to Herrin and Tipton (1975) and Morales-Malacara (2001), they share broad pear-shaped sternal plate with a somewhat narrow or broadly rounded anterior border, some enlarged ventral hysterosomal setae, proteronotal and poststigmal setae very small in females and males, and sternogenital plate with rounded lateral borders.

Periglischrus caligus is closely related to P. leptosternus Morales-Malacara & López-Ortega, 2001 from caligus species group (Morales-Malacara 2001). They share the dark foveae pattern on dorsal plate and a sternal plate with a subpentagonal outline and a pointed anterior border, and males with a small sternogenital plate with weakly sclerotised anterolateral borders and small sternogenital setae (Morales-Malacara 2001). Herrin and Tipton (1975) previously included P. caligus in subgroup A from group II (P. paracaligus Herrin and Tipton, 1975, P. paravargasi and P. vargasi) due to their morphological similarity (all dorsal proteronotal setae large, long, stout, with first and second pairs apart from each other by a distance larger than second and third pairs; proximal anterodorsal (ad) seta of femur–tibia I, and tibia II small to minute), and host associations (genera Glossophoga (P. caligus), Leptonycteris (P. paracaligus) and Anoura (P. paravargasi and P. vargasi)). Meanwhile, Morales-Malacara 2001 indicated P. caligus from caligus species group and included the other species (P. paracaligus, P. paravargasi and P. vargasi) from vargasi species-group, along with P. empheresotrichus Morales-Malacara, Castaño-Meneses & Klompen, 2020, and P. calcariflexus Morales-Malacara & López-Ortega, 2023.

Periglischrus paravarvagi is a member of vargasi species-group, along P. vargasi, P. paracaligus, P. calcariflexus, and P. empheresotrichus. The group share a sigilla or foveal arrangement, unique scale-like interfoveal ornamentation pattern on dorsal plate, long proteronotal setae and a subpentagonal sternal plate with anterior subtriangular border on female, and males sternogenital plate usually with unsclerotized anterolateral corners, with medium or moderately long sized sternal setae (Morales-Malacara 2001). Additionally, this species-group is associated with three genera of Glossophagini bats: Anoura, Monophyllus, and Leptonycteris (Morales-Malacara et al. 2020; Morales-Malacara and López-Ortega 2023).

Periglischrus herrerai is a member of hopkinsi species group, similar to P. hopkinsi Machado-Allison, 1965a in having sternal plates with a subpentagonal outline and a subtriangular anterior border. A small cross-shaped crack on the dorsal plate occurs in males of P. herrerai, and both sexes of P. hopkinsi (Morales-Malacara 2001), and males of P. herrerai have a unique reticulated sternogenital shield. Furthermore, sharing the distance between Pn1–Pn2 ≤ Pn2–Pn3 and proximal anterodorsal (ad) seta of tibia II large (Herrin and Tipton 1975). P. herrerai is associated with bats of the genus Desmodus, while P. hopkinsi is associated with the Glossophagini bat Lionycteris spurelli and Lonchophylla robusta (Herrin and Tipton 1975).

Periglischrus iheringi belongs to iheringi species-group, along P. ojastii Machado-Allison, 1964, sharing the pronounced shoulders on anterolateral dorsal plate and sternal and sternogenital plates similarly shaped (Herrin and Tipton 1975; Morales-Malacara 2001). Nevertheless, P. iheringi females have Pn1 minute to other setae and on dorsal plate (vs. subequal in length to the other setae and off dorsal plate), and both sexes with distances between Pn1-Pn2 > Pn2-Pn3 (vs. Pn1-Pn2 < Pn2-Pn3) (Herrin and Tipton 1975). Herrin and Tipton (1975) also grouped these two species (their group III), along with P. ramirezi Machado-Allison & Antequera, 1971, based on the shape of the sternal plate (especially P. ojastii and P. iheringi) and males with 7-8 pairs of setae on intercoxal area IV and sternogenital setae longer, St1 seta extending posteriorly to or beyond level St2 setae bases or just beyond first pair of pores. On the other hand, Morales-Malacara (2001) categorized P. ramirezi from delfinadoae species-group, along with P. delfinadoae Dusbábek, 1967, still belonging to acutisternus-clade. This placement occurred despite limited morphological similarities and its association with a different bat clade. P. delfinadoae is associated to stenodermatini bats and P. ramirezi to macrotine bats.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Program for Technological Development in Tools for Health-PDTISFIOCRUZ for use of its facilities, especially to Renata de B. R. Oliveira who assisted with sequencing. This study was supported by resources from FAPEMIG-VALE (Edital 07/2018-Research in Speleology, process RDP 00107-18). The field trip to the Pains municipality region was supported by FAPEMIG-VALE (Edital 07/2018-Research in Speleology, process RDP-00079-18). ARP is supported by a PQ–2 CNPq fellowship (process 309979/2021-8) and BKGA and SGSC by a FAPEMIG scholarship (Graduate Support Program PAPG). SGSC thanks the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES – Print, Finance Code 001) for providing his scholarships. This study is part of the first author's PhD thesis in the post-graduation Program in Zoology-UFMG.

References

- Almeida J.C., Gettinger D., Gardner S.L. 2016a. Taxonomic review of the wingmite genus Cameronieta (Acari: Spinturnicidae) on neotropical bats, with a new species from Northeastern Brazil. Comp. Parasitol., 83(2): 212-220.F https://doi.org/10.1654/4788i.1

- Almeida J.C., Gomes L.A.C., Owen R.D. 2018. Morphometric variation in Periglischrus torrealbai (Acari: Spinturnicidae) on three species of host bats (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) with a new record of host species. Parasitol. Res., 117(1): 257-264.F https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-017-5700-y

- Almeida J.C., Martins M.A., Guedes P.G., Peracchi A.L., Serra-Freire N.M. 2016b. New records of mites (Acari: Spinturnicidae) associated with bats (Mammalia, Chiroptera) in two Brazilian biomes: Pantanal and Caatinga. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet., 25(1): 18-23.F https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612016005

- Almeida J.C., Serra-Freire N., Peracchi A. 2015. Anatomical location of Periglischrus iheringi (Acari: Spinturnicidae) associated with the great fruit-eating bat (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet., 24(3): 361-364.F https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015022

- Almeida J.C., Silva S.S.P., Serra-Freire N.M., Cruz A. P, Mendes C.P.A., Peracchi A.L. 2007. Ácaros (Mesostigmata, Spinturnicidae e Macronyssidae) em Artibeus lituratus (Olfers, 1818) (Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae) no Parque Estadual da Pedra Branca, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. In: Anais do VIII Congresso de Ecologia do Brasil, 23 a 28 de setembro de 2007, Caxambu: MG. p. 1-2.

- Almeida J.C., Silva S.S.P., Serra-Freire N.M., Peracchi A.L. 2010. Diversidade ectoparasitológica em morcegos na Fazenda Marambaia, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. Chiroptera Neotropical, 16(1 Supl.): 118-121.

- Almeida J.C., Silva S.S.P., Serra-Freire N.M., Valim M.P. 2011. Ectoparasites (Insecta and Acari) associated with bats in southeastern Brazil. J. Med. Entomol., 48(4): 753-757.F https://doi.org/10.1603/ME09133

- Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schäffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25(17): 3389-3402.F https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/25.17.3389

- Azevedo A., Linardi P., Coutinho M. 2002. Acari ectoparasites of bats from Minas Gerais, Brazil. J. Med. Entomol., 39(3): 553-555.F https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-39.3.553

- Bezerra R., Bocchiglieri A. 2018. Association of ectoparasites (Diptera and Acari) on bats (Mammalia) in a restinga habitat in northeastern Brazil. Parasitol. Res., 117(11): 3413-3420.F https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-018-6034-0

- Beron P. 2020. Acarorum Catalogus VI. Order Mesostigmata. Gamasina: Dermanyssoidea (Rhinonyssidae, Spinturnicidae). Advanced Books, 1, e54206.F https://doi.org/10.3897/ab.e54206

- Bouckaert R., Heled J., Kühnert D., Vaughan T., Wu C., Xie D., Suchard M., Rambaut A., Drummond A. 2014. BEAST 2: A Software Platform for Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis. PLoS Computational Biology, 10 (4): e1003537.F https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537

- Confalonieri U.E.C. 1976. Sobre a família Spinturnicidae Oudemans, 1902 e seus hospedeiros no Brasil, com estudo biométrico de Periglischrus iheringi Oudemans, 1902 e Periglischrus ojastii Machado-Allison, 1964 (Arthropoda: Acari: Mesostigmata) [Dissertação de Mestrado]. Rio de Janeiro: Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro. pp. 92.

- Costa S., Klompen H., Bernardi L., Gonçalves L., Ribeiro D., Pepato A. 2019. Multi-instar descriptions of cave dwelling Erythraeidae (Trombidiformes: Parasitengona) employing an integrative approach. Zootaxa, 4717(1): 137-184.F https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4717.1.10

- Dabert M., Bigoś A., Witaliński W. 2011. Dna barcoding reveals andropolymorphism in Aclerogamasus species (Acari: Parasitidae). Zootaxa, 3015(1): 13-20.F https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3015.1.2

- Dantas-Torres F., Soares F.A.M., Ribeiro C.E.B.P., Daher M.R.M., Valença G.C., Valim M.P. 2009. Mites (Mesostigmata: Spinturnicidae and Spelaeorhynchidae) associated with bats in northeast Brazil. J. Med. Entomol., 46(3): 712-715.F https://doi.org/10.1603/033.046.0340

- Deunff J., Whitaker Jr J. O., Kurta A. 2011. Description of nymphal stages of Periglischrus cubanus (Acari, Spinturnicidae), parasites from Erophylla sezekorni bombifrons (Chiroptera) from Puerto Rico with observations on the nymphal stages and host-parasite relationships within the genus Periglischrus. J. Med. Entomol., 48(4): 758-763. https://doi.org/10.1603/ME10234

- Drummond A.J., Suchard M.A., Xie D., Rambaut A. 2012. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 29: 1969-1973.F https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mss075

- Dusbábek F. 1968. Los ácaros cubanos de la familia Spinturnicidae (Acarina), con notas sobre su especificidad de hospederos. Poeyana serie A. 57: 1-31.

- Edgar R. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research, 32(5): 1792-1797.F https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkh340

- Evans G.O. 1963. Observations on the chaetotaxy of the legs in the free-living Gamasina (Acari: Mesostigmata). Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Zoology, 10: 275-303. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.part.20528

- Evans G.O. 1968. The external morphology of the post-embryonic developmental stages of Spinturnix myoti Kol. (Acari: Mesostigmata). Acarologia, 10(4): 589-608.

- Domrow R. 1972. Acari Spinturnicidae from Australia and New-Guinea. Acarologia, 13(4): 552-584.

- Furman D.P. 1966. The Spinturnicid mites of Panama, pp. 125-166. In: Wenzel R.L., Tipton V. J. (eds.). Ectoparasites of Panama, Field Museum of Natural History. Chicago: Illinois, USA. p. 125-166.F https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.2633

- Gettinger D. 2018. Checklist of Bloodfeeding Mites (Acari: Spinturnicidae) from the wings of Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in the Manú Biosphere Reserve, Peru. MANTER: Journal of Parasite Biodiversity, 10: 1-9.F https://doi.org/10.13014/K2DJ5CVZ

- Gettinger D., Gribel R. 1989. Spinturnicid Mites (Gamasida: Spinturnicidae) Associated with Bats in Central Brazil. J. Med. Entomol., 26(5): 491-493.F https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/26.5.491

- Gomes-Almeida B. K., Costa S. G., Ribeiro D. B., Bernardi L. F., Pepato A. R. 2023. First multi-instar descriptions of cave-dwelling Whartonia Ewing, 1944 (Parasitengona, Leeuwenhoekiidae) from Brazil through integrative taxonomy. Systematic and Applied Acarology, 28(3), 568-606.F https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.28.3.13

- Herrin C.S., Tipton V.J. 1975. Spinturnicid mites of Venezuela (Acarina: Spinturnicidae)-Parte 1. Brigham Young University Science Bulletin-Biological Series, 20(2): 1-72. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.part.5666

- Hoffmann A. 1944. Periglischrus vargasi n.sp. (Acarina: Parasitidae). Revista del Instituto de Salubridad y Enfermedades Tropicales, México 5: 91-96.

- Kalyaanamoorthy S., Minh B.Q., Wong T.K.F., von Haeseler A., Jermiin L.S. 2017. ModelFinder: Fast Model Selection for Accurate Phylogenetic Estimates. Nat. Methods, 14: 587-589.F https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4285

- Klimov P.B., O'Connor B.M., Chetverikov P.E., Bolton S.J., Pepato A.R., Mortazavi A.L., Tolstikov A.V., Bauchan G.R., Ochoa R. 2018. Comprehensive phylogeny of acariform mites (Acariformes) provides insights on the origin of the four-legged mites (Eriophyoidea), a long branch. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol., 119, 105-117.F https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2017.10.017

- Knowles L.L., Carstens B.C. 2007. Delimiting Species without Monophyletic Gene Trees. Syst. Biol., 56(6): 887-895.F https://doi.org/10.1080/10635150701701091

- Kolenati F. A. 1857. Synopsis prodroma der Flughaut-Milben (Pteroptida) der Fledermäuse. Wien Entomol. Monatschr. 1: 59-61.

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol., 33(7):1870-1874.F https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054

- Łaydanowicz J., Mąkol J. 2010. Correlation of heteromorphic life instars in terrestrial Parasitengona mites and its impact on taxonomy-the case of Leptus molochinus (CL Koch, 1837) and Leptus ignotus (Oudemans, 1903) (Acari: Trombidiformes: Prostigmata: Erythraeidae). J. Nat. Hist., 44(11-12): 669-697.F https://doi.org/10.1080/00222930903383560

- Lourenço E.C., Gomes L.A.C., Viana A.O., Famadas K.M. 2020. Co-occurrence of Ectoparasites (Insecta and Arachnida) on Bats (Chiroptera) in an Atlantic Forest Remnant, Southeastern Brazil. Acta Parasit., 65: 750-759.F https://doi.org/10.2478/s11686-020-00224-z

- Lourenço E.C., Patrício P.M.P., Famadas K.M. 2016. Community components of spinturnicid mites (Acari: Mesostigmata) parasitizing bats (Chiroptera) in the Tinguá Biological Reserve of Atlantic Forest of Brazil. Int. J. Acarol., 42(2): 63-69.F https://doi.org/10.1080/01647954.2015.1117525

- Machado-Allison, C. 1964. Notas sobre Mesostigmata Neotropicales II. Cuatro nuevas species de Periglischrus Kolenati, 1857. (Acarina, Spinturnicidae). Rev. Soc. Mex. Hist. Nat., 25: 193-207.

- Machado-Allison, C.E. 1965a. Las espécies del gêneros Periglischrus Kolenati 1857 (Acarina, Mesostigmata, Spinturnicidae). Acta Biol. Venez., 4:259-348.

- Machado-Allison, C.E. 1965b. Notas sobre Mesostigmata Neotropicales III. Cameronieta thomasi: nuevo gênero y nueva especies parasita de Chiroptera (Acarina, Spintumicidae). Acta Biol. Venez., 4:243-258.

- Machado-Allison C., Antequera R. 1971. Notes on neotropical Mesostigmata VI: Four New Venezuelan species of the genus Periglischrus (Acarina; Spinturnicidae). Smithsonian Contrib. Zool., 93: 1-16.F https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00810282.93

- Morales-Malacara J.B. 2001. New morphological analysis of the bat wing mites of the genus Periglischrus (Acari: Spinturnicidae). In: Halliday R.B., Walter D.E., Proctor H.C., Norton R.A., Colloff M.J. (eds.). Acarology: Proceedings of the 10th International Congress. Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing. p. 185-193.

- Morales-Malacara J.B., Aldana L.Y.M., Reyes-Novelo E., Almazán-Marín C.E., Ruiz-Piña H.A., Cuxim-Koyoc A., Aguilar-Setién Á., Colín-Martínez H., García-Estrada C., Ojeda M. 2018. Redescription of Periglischrus herrerai (Acari: Spinturnicidae) Associated to Desmodus rotundus (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae: Desmodontinae), with a description of adult Female Heteromorphism and an Analysis of its Variability Throughout the Neotropics. J. Med. Entomol., 55(2): 300-316.F https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjx202

- Morales-Malacara J., Castaño-Meneses G., Klompen H., Mancina C. 2020. New species of the genus Periglischrus (Acari: Spinturnicidae) from Monophyllus bats (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) in the West Indies, including a morphometric analysis of its intraspecific variation. J. Med. Entomol., 57(2): 418-436.F https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjz198

- Morales-Malacara J.B., Juste J. 2002. Two new species of the genus Periglischrus (Acari: Mesostigmata: Spinturnicidae) on two bat species of the genus Tonatia (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) from southeastern Mexico, with additional data from Panama. J. Med. Entomol., 39(2): 298-311.F https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-39.2.298

- Morales-Malacara J.B., López-Ortega G. 2001. A new species of the genus Periglischrus (Acari: Mesostigmata: Spinturnicidae) on Choeronycteris mexicana (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) in Central Mexico. J. Med. Entomol., 38(2): 153-160.F https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-38.2.153

- Morales-Malacara J.B., López-Ortega G. 2023. A new species of the genus Periglischrus (Acari: Spinturnicidae) on Leptonycteris nivalis (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) from Mexico, including a key to species of the vargasi species group. J. Med. Entomol., 60 (1):73-89.F https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjac151

- Moras L., Bernardi L., Graciolli G., Gregorin R. 2013. Bat flies (Diptera: Streblidae, Nycteribiidae) and mites (Acari) associated with bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in a high-altitude region in southern Minas Gerais, Brazil. Acta Parasitol., 58(4):556-563F https://doi.org/10.2478/s11686-013-0179-x

- Nguyen L.-T., Schmidt H.A., von Haeseler A., Minh B.Q. 2015. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32: 268-274.F https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu300

- Oudemans, A.C. 1902. Acarologische Aanteekeningen. Entomol. Berichten. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.part.1124

- Oudemans A.C. 1903. Notes on Acari, Eighth series. - Tijdschr. Nederl. Dierk. Vereen., 8(2): 70-92.

- Puillandre N., Brouillet S., Achaz G. 2021. ASAP: Assemble species by automatic partitioning. Molecular Ecology Resources 2(2): 609-620.F https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13281

- Rambaut A., Suchard M., Xie D., Drummond A. 2014. Tracer. Version 1.6. Available from: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/ (accessed 30 March 2022)

- Ratnasingham S., Hebert P. D. N. 2007. BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System ( http://www.barcodinglife.org). Molecular ecology notes, 7(3), 355-364.F https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01678.x

- Ratnasingham S., Hebert P. D. N. 2013. A DNA-based registry for all animal species: The Barcode Index Number (BIN) system. PLoS One, 8, e66213.F https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066213

- Reid N., Carstens B. 2012. Phylogenetic estimation error can decrease the accuracy of species delimitation: a Bayesian implementation of the general mixed Yule-coalescent model. BMC evolutionary biology, 12: 196.F https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-12-196

- Rudnick A. 1960. A revision of the mites of the family Spinturnicidae (Acarina). University of California. Publication in Entomology, 17: 157-284.

- Schlick-Steiner B.C., Steiner F.M., Seifert B., Stauffer C., Christian E., Crozier R.H. 2010. Integrative taxonomy: a multisource approach to exploring biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Entomol., 55: 421-438.F https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085432

- Silva C.L., Valim M.P., Graciolli G. 2017. Ácaros ectoparasitos de morcegos no estado de Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. Iheringia, Sér. Zool., 107(suppl): e2017111.F https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-4766e2017111

- Silva C., Graciolli G. 2013. Prevalence, mean intensity of infestation and host specificity of Spinturnicidae mites (Acari: Mesostigmata) on bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in the Pantanal, Brazil. Acta Parasitol., 58(2): 174-9.F https://doi.org/10.2478/s11686-013-0134-x

- Silva C.D.L., Graciolli G., Rui A.M. 2009. Novos registros de ácaros ectoparasitos (Acari, Spinturnicidae) de morcegos (Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae) no Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Chiroptera Neotropical, 15(2): 469-471.

- Vidal L., Bernardi L., Talamoni S. 2021. Host-parasite associations in a population of the nectarivorous bat Anoura geoffroyi (Phyllostomidae) in a cave in a Brazilian ferruginous geosystem. Subterr. Biol., 39: 63-77.F https://doi.org/10.3897/subtbiol.39.64552

- Von Heyden C. H. G. 1826. Versuch einer systematischen Eintheilung der Acariden. - Isis (Oken), 18: 608-613.

- Webb J.P., Loomis R.B. 1977. Ectoparasites. In: Baker RJ, Jones JK Jr, Carter DC, editors. Biology of bats of the new world family Phyllostomidae, Part II. Lubbock: Texas Tech University, 57-120 p.

- Zamora-Mejías D., Ojeda M., Medellín R.A., Rodríguez-Herrera B., Morales-Malacara J.B. 2022. Morphological variation in the wing mite Periglischrus paracaligus (Acari: Spinturnicidae) associated with different moving strategies of the host Leptonycteris yerbabuenae (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). J. Med. Entomol., 59(4):1291-1302.F https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjac058

2023-09-22

Date accepted:

2024-04-03

Date published:

2024-04-05

Edited by:

Roy, Lise

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

2024 Gomes-Almeida, Brenda Karolina; Diório, Gabriel Félix; Costa, Samuel Geremias dos Santos and Pepato, Almir Rogério

Download the citation

RIS with abstract

(Zotero, Endnote, Reference Manager, ProCite, RefWorks, Mendeley)

RIS without abstract

BIB

(Zotero, BibTeX)

TXT

(PubMed, Txt)