First record of the tomato red spider mite, Tetranychus evansi Baker & Pritchard (Acari: Tetranychidae) in Mexico, from cultivated and wild solanaceous plants

Monjarás-Barrera, José Irving  1

and Sanchez-Peña, Sergio R.

1

and Sanchez-Peña, Sergio R.  2

2

1Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Facultad de Enología y Gastronomía, Carretera Transpeninsular Ensenada-Tijuana #3917, Fraccionamiento Playitas, Ensenada, Baja California, México 22860.

2✉ Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Departamento de Parasitología Agrícola, Calzada Antonio Narro #1923, Buenavista, Saltillo, Coahuila, México 25315.

2024 - Volume: 64 Issue: 1 pages: 164-171

https://doi.org/10.24349/78jc-6nevOriginal research

Keywords

Abstract

Introduction

Solanaceous plants include important crops worldwide. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) in its different varieties, and potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) are two of the most important crops in Mexico: for tomato, 49,287 ha were planted in 2022, with a value of 1,566,032 USD; for potato, 60,102 ha were planted in 2022, with a value of 803,805 USD (SIAP 2023). The states of Baja California, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas contributed 2.9% of total Mexican tomato production in 2022 (SIAP 2023); these areas include high-technology greenhouses with significant production output. For potato, the state of Nuevo Leon grew 5.4% of Mexico´s production in 3,214 ha with a value of 78,523 USD in 2022 (SIAP 2023; Delgado-Luna et al. 2022).

Yield of solanaceous crops is affected by diseases and pests including mites (Ong et al. 2020; Ascencio-Alvarez et al. 2018; Lugo-Sánchez et al. 2019). Of these, the two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch, the broad mite, Polyphagotarsonemus latus Banks and the cyclamen mite, Phytonemus pallidus Banks attack tomato in Sinaloa, the main producing state in Mexico (Lugo-Sánchez et al. 2019).

One of the most important pest species of the genus Tetranychus worldwide on Solanaceae is the tomato red spider mite, Tetranychus evansi Baker & Pritchard (TRSM) (Navajas et al. 2013). This mite has been reported in 56 countries, associated with at least 147 plant species within 36 botanical families (Migeon and Dorkeld, 2023). In the American continent, TRSM is distributed in the Neotropical region in Argentina, Brazil, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands; in the Nearctic region it is recorded from Florida, and the USA-Mexico border states of Arizona, Texas and California (Wene 1956 [as Tetranychus marianae McGregor]; de Moraes et al. 1987; Navajas et al. 2013; Migeon and Dorkeld 2023). Morphologically unclear samples resembling T. evansi were reported from the Pacific coast of Jalisco, Mexico (de Moraes et al. 1987).

Tetranychus evansi elicits some unique physiological responses in attacked plants, suppressing important defense pathways, therefore inflicting damage in a different way to some of its congeners (Sarmento et al. 2011). TRSM is usually not considered a severe pest in its native host range (Brazil); however, in northern Argentina it is widespread and the most abundant tetranychid mite collected, with very high populations on tomato and other solanaceous plants (Guanilo et al. 2010; Furtado et al. 2007). It is a severe pest in sites of sub-Saharan Africa, where it can cause up to 90% crop loss of tomato (Migeon et al. 2009; Boubou et al. 2011; Savi et al. 2019) and it is considered a primary, invasive pest of solanaceous crops in Europe and the Mediterranean basin (EPPO 2022).

Invasive populations of T. evansi represent a threat to solanaceous crop production worldwide. Timely detection of invasive pests and diseases is of utmost importance to establish proper control measures (Migeon et al. 2009). In this study we report for the first time the presence of T. evansi in Mexico, from cultivated (tomato and potato) and wild (nightshade) solanaceous hosts.

Material and methods

Sample collection

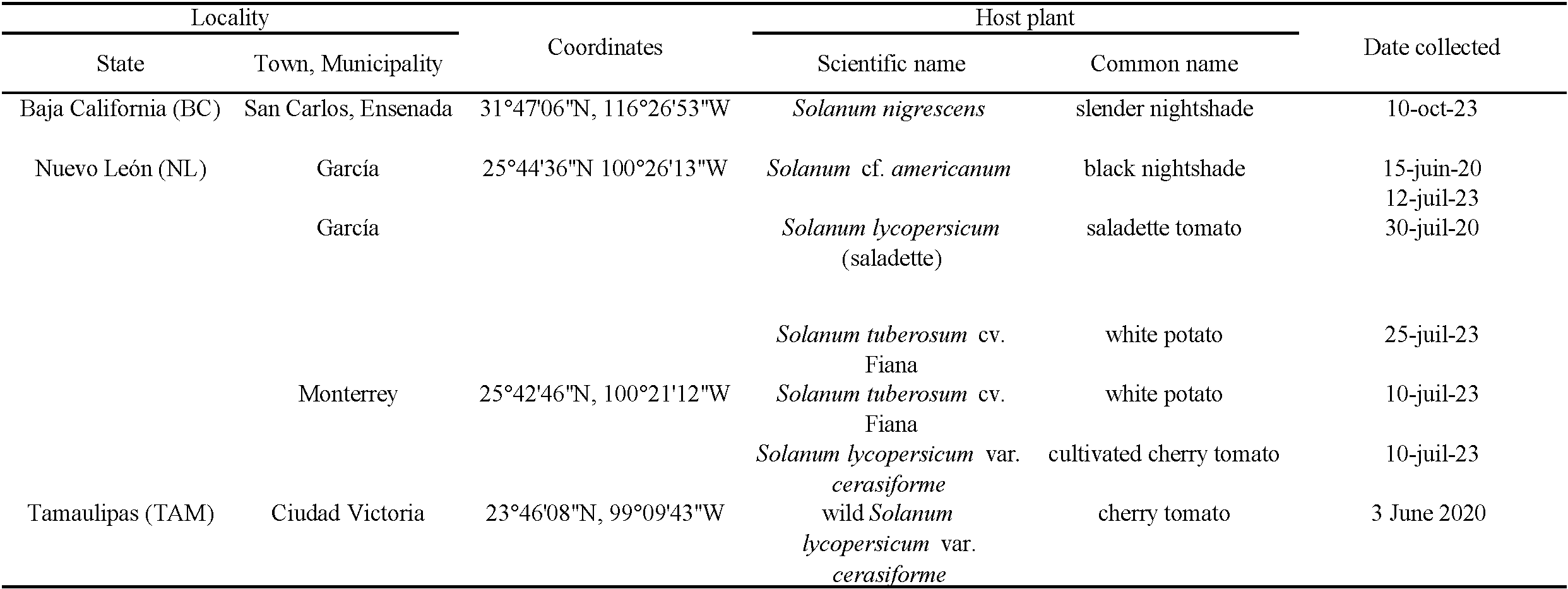

Leaves of wild and cultivated solanaceous plants infested by suspect TRSM were collected at four sites from three states in Mexico (Table 1).

Morphological identification

Samples were examined using a stereomicroscope, placing mites in Hoyer's medium on slides (EPPO 2022). A sample of 170 females were examined from García (Nuevo Leon state). For Ciudad Victoria (Tamaulipas state) and Ensenada (Baja California state), 10 males and 10 females were examined from each population. Mites on slides were examined under an Olympus Vanox phase contrast microscope at Laboratorio Nacional de Microscopía Avanzada (National Laboratory of Advanced Microscopy), Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE) and identified according to Baker and Pritchard (1960), de Moraes et al. (1987), Seeman and Beard (2011) and EPPO (2022); characteristics observed included aedeagus, tarsus I and empodium, and pregenital striae.

Females from García, Nuevo León, and females and males from Baja California and Tamaulipas were deposited (as slides) at ''Colección Nacional de Ácaros'' (CNAC), Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Mexico City, Mexico.

Molecular analysis

Molecular methods for DNA sequencing of a fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (COI) region were performed at Biociencia, Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, Mexico (http://www.biociencia.com.mx ![]() ). DNA was extracted from 30 females and nymphs from Garcia, Nuevo Leon, following the cetrimonium bromide (CTAB) procedure in Doyle and Doyle (1987) modified by SENASICA (2017). Primers used LCO1490: 5′-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′ and HC02198: 5′-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′ were as in Folmer et al. (1994). Amplification conditions are described in SENASICA (2017). Sequencing of PCR products was provided by Biociencia. Sequences were compared (BLAST) in the NCBI database to determine percent species identity.

). DNA was extracted from 30 females and nymphs from Garcia, Nuevo Leon, following the cetrimonium bromide (CTAB) procedure in Doyle and Doyle (1987) modified by SENASICA (2017). Primers used LCO1490: 5′-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′ and HC02198: 5′-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′ were as in Folmer et al. (1994). Amplification conditions are described in SENASICA (2017). Sequencing of PCR products was provided by Biociencia. Sequences were compared (BLAST) in the NCBI database to determine percent species identity.

Results and discussion

Morphological observations

The mite was confirmed as T. evansi from morphological examination of females (populations from all three states) and males in the Tamaulipas and Baja California populations. No males were found in the Garcia, Nuevo Leon sample (n = 170). Populations of T. evansi can be strongly female-biased (de Moraes and McMurtry 1987). The size and shape of the aedeagus (Figure 1A, B) closely match descriptions in Baker and Pritchard (1960), de Moraes et al. (1987), Seeman and Beard (2011) and EPPO (2022). For females, differences between tarsus I of T. evansi and T. marianae were used (de Moraes et al. 1987). The pregenital striae are entire; dorsal striae are longitudinal (not transverse) between setae e1–e1 , forming a diamond or rhomboid shape between setae e1–f1 in females (Seeman and Beard 2011).

Molecular analysis

A COI sequence 471 bp long (GenBank accession PP060370) was obtained from Garcia (Nuevo Leon state) samples. A BLAST analysis resulted in 97.21-100% identity and 98% query cover with T. evansi sequences in Genbank (for example, Boubou et al. 2011). The next more similar species was Tetranychus truncatus Ehara with a distant 89.5% identity (11.5% divergence). These values indicate that samples are not conspecific with T. truncatus, but are conspecific with TRSM. Within the Tetranychidae, Ben-David et al. (2007) suggested a minimum of 98% identity for species separation using COI and ITS2 markers. They emphasize that solid morphological characterization is essential for designation of correct reference sequences.

Ten COI haplotypes have been reported in T. evansi; these cluster into two lineages or clades (Boubou et al. 2011; Knegt et al. 2020). Clade I is present in Africa, Asia, the Mediterranean and South America; Clade II includes Mediterranean and South American populations only. Our sequence from Mexico belongs in clade I and it is identical to haplotype TW (GenBank FJ440677) reported by Gotoh et al. (2009) from Wufeng, Taiwan and designated as haplotype H4 (Boubou et al. 2011); it is also identical to later reports: MT0196779.1 and MT019789.1 (Mo′atza Azorit Emeq Hamaayanot, Israel); MT019707.1 (Tokyo, Japan); MT019694.1 (Andalucía, Spain); and MT0196732.1 and MT019792.1 (Canary Islands, Spain) (Knegt et al. 2020). This haplotype is widespread in Africa (Niger), Europe (the Mediterranean: Algeria, Greece, Israel, southern and southeastern Spain, and Tunisia), also, from the Canary Islands (Spain) and Asia (Japan, Taiwan) (Boubou et al. 2011; Knegt et al. 2020).

This is the first report of clade I from North America. In general, clade I mites have a higher invasive potential than mites from clade II (Meynard et al. 2013; Santamaría et al. 2018; Knegt et al. 2020).

Field observations

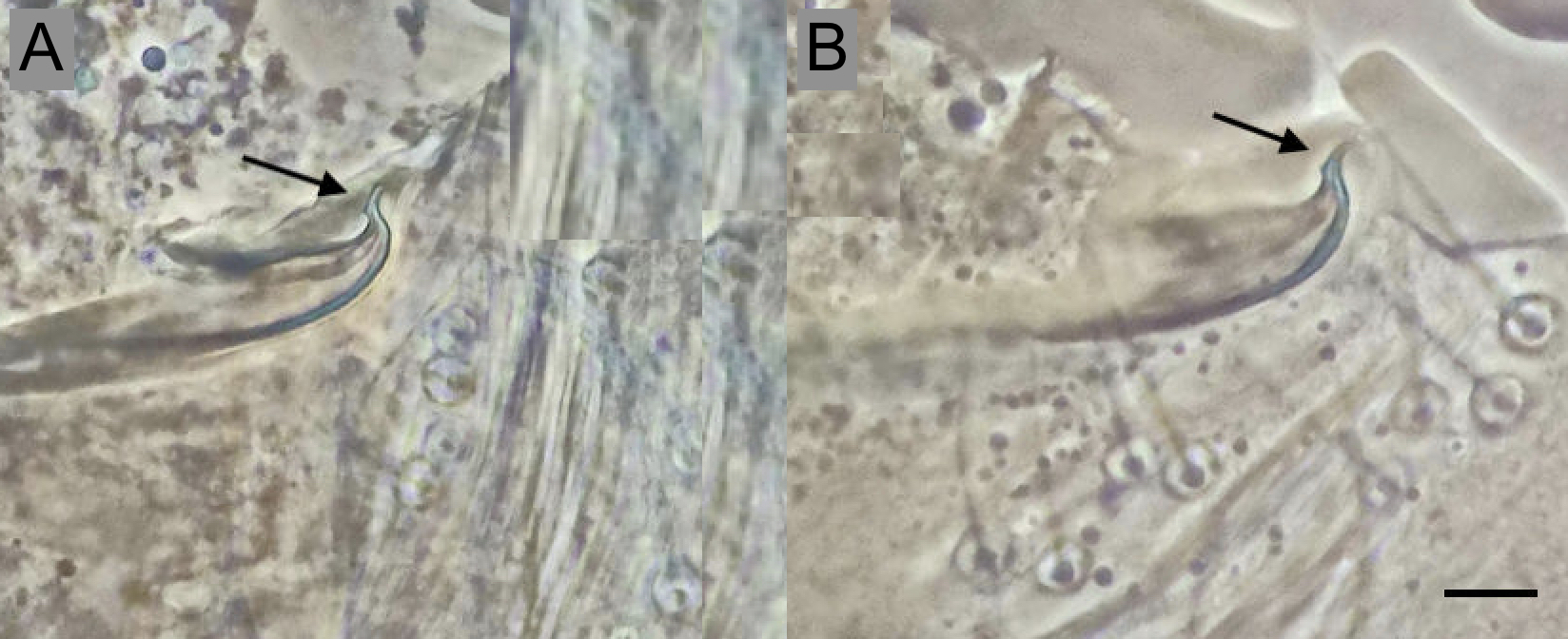

TRSM populations reported in this work are listed in Table 1. All life stages including eggs and overlapping generations were observed on these plants. Mites were initially observed on nightshades or ''hierba mora'' (Solanum nigrescens Mart. & Gal. and Solanum cf. americanum Mill.) at Ensenada (Baja California) (on S. nigrescens) and in García (Nuevo León) respectively (Figure 2A). These non-cultivated plants were in vacant lots of residential areas, along urban and rural roads and other weedy disturbed areas. Severe infestations of TRMS leading to leaf necrosis or plant death were observed on nightshades. These and very similar nightshades appear to be worldwide frequent hosts for TRSM (Qureshi et al. 1969; Tsagkarakou et al. 2007; Santamaría et al. 2018). The capacity to manipulate plant defenses and a high intrinsic growth rate might contribute to observed high populations (Sarmento et al. 2011; Navajas et al. 2013). Clade I mites can attain very high population levels on both nightshades and tomato (Santamaría et al. 2018).

TRSM was also observed in high levels on tomato and potato plants grown in home gardens in 2020 and 2023, in the urban area of Monterrey and Garcia, Nuevo Leon state. In 2023, mixed infestations of TRSM and very low numbers of much darker unidentified spider mites, were observed on the same tomato plants. The darker unidentified mite was observed only on newer tomato growth, while older growth was more heavily infested by TRSM. This could result from an initial infestation by TRSM (see Sarmento et al. 2011; Navajas et al. 2013); in the field this species is usually dominant over other spider mites, reducing the absolute and relative abundance of other Tetranychus species, including the widespread, darker-colored T. urticae (Ferragut et al. 2013; Azandémè-Hounmalon et al. 2015); as mentioned, this can result from manipulation of plant defenses and a high intrinsic growth rate (Sarmento et al. 2011; Navajas et al. 2013). In Nuevo Leon state (García and Monterrey sites) the mites infested saladette tomato plants late in the season, after flowering. Fruits were damaged, showing numerous tiny pale spots or blotches from feeding by hundreds of mites (Figure 2B). Eventually most foliage was killed and the plants died prematurely, before fruit production was complete. Both varieties of tomatoes (saladette and cherry) at Nuevo Leon were severely impacted. We lack quantitative data, but damage on potato was also particularly intense and rapid, perhaps worse than on tomato; in time, all potato plants were completely wilted and died.

Considering this apparent geographical expansion of T. evansi into Mexico, it is pertinent to comment on its host plant range. The mite is considered oligophagous (Guanilo et al. 2010; Ferragut et al. 2013). In our observations, the mites infested only solanaceous plants, and the mite masses thus produced (Figure 3) did not colonize or damage other plants (from at least 8 families) in physical contact with infested plants. Reports of host plants should verify full completion of the arthropod´s life cycle on these plants (i.e. true ''host plants'') and distinguish these from ''food plants'' (those where the arthropod can feed, but not reproduce; food plants temporarily support arthropod survival in the absence of true hosts) and from overwintering, shelter and incidental plants (Mendonça et al. 2011; Reyes-Corral et al. 2021; Delgado-Luna et al. 2022).

At Garcia and Monterrey, plants not colonized by TRSM, grown in heavily infested unsprayed home gardens included aloe or sábila (Aloe vera L.), avocado (Persea americana cv. ''Hass''), cacti (Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill and Nopalea cochenillifera (L.) Salm-Dyck), Mexican lime (Citrus aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle), seedlings of oaks (Quercus polymorpha Schlecht. & Cham. and Q. fusiformis Small), orange (Citrus × aurantium L.), papaya (Carica papaya L.), peace lily (Spathiphyllum wallisii Regel) and peppermint (Mentha × piperita L.). Therefore, at least in these gardens, the mite appeared to be quite oligophagous on Solanaceae (Guanilo et al. 2010; Migeon and Dorkeld 2022; Da-Costa et al. 2022). On papaya, there were orange-colored masses of mites, apparently engaging in wind dispersal behavior (ballooning) (Figure 3). Notwithstanding mite masses, no mite reproduction was observed, and papayas were not damaged; suggesting that the mites came from adjacent, heavily infested tomato plants. Interestingly, no noticeable populations were observed on chili pepper plants (Solanaceae) growing within 1 m of tomato plants infested with very high densities of TRSM. These unharmed pepper plants were six mature plants of a cultivar (jalapeño, Capsicum annuum var. annuum L.) and two plants of wild (piquín) chili pepper (C. annuum var. glabriusculum [Dunal]). Chili pepper is listed as severely impacted in Benin, Africa (Azandeme-Hounmalon 2022). This could be compared to the fact that wild chili pepper has resistance traits against Tetranychus merganser Boudreaux (Chacón-Hernandez et al. 2020).

The presence of T. evansi represents an additional challenge for production of solanaceous crops in Mexico. Ecological studies of the mite are required, both in agricultural and non-agricultural settings. Its pest status has been variable over time and space, in both native and invaded areas (Navajas et al. 2013; Azandémè-Hounmalon et al. 2022; F. Ferragut, personal communication). Its presence in Arizona, California and Texas (see de Moraes et al. 1987 and references therein; Ferragut & Escudero, 1999; Migeon et al. 2009), states bordering Mexico, can explain its detection in widely separated locations of this country. Containment in Mexico thus would prove difficult. It was recorded decades ago right at the Mexican border: outbreaks on tomato at unspecified sites of the lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas (Weslaco?) (Wene 1956) and in 1957 at Donna, Texas (de Moraes et al. 1987), both sites adjacent to Tamaulipas state and close to Nuevo Leon state (Migeon et al. 2009; Navajas et al. 2013; Migeon and Dorkeld 2023). In the climatic analysis and modelling by Migeon et al. (2009) and Meynard et al. (2013), extensive areas of these states appear as highly suitable for TRSM; parts of Baja California state are moderately suitable. Thus, TRSM is likely to be present in additional localities in the country. On the other hand, sampling effort in solanaceous crops is limited, making it difficult to detect and identify mite species. Similarly, it is important to continue exploring native and invaded areas for natural enemies (de Moraes and McMurtry 1985; Navajas et al. 2013; Guanilo et al. 2010; Furtado et al. 2014; Dayoub et al. 2022) towards the inclusion of biological control among other sustainable management strategies of TRSM in Mexico.

Acknowledgement

The first author thanks the support provided through of project 440/3418 by SICASPI-UABC. Also, Diego L. Delgado-Álvarez, Ph.D, of National Laboratory of Advanced Microscopy, CICESE, Ensenada, Mexico for support with phase contrast microscopy. The corresponding author thanks Dirección de Investigación, UAAAN, for funding. The observations by F. Ferragut, A. Migeon, G. de Moraes, and an anonymous reviewer contributed to improvement of the manuscript.

References

- Ascencio-Alvarez A., Avila-Perches M.A., Dorantes-González J.R.A., O-Olán M., Espinosa-Trujillo E., Palemón-Alberto F., Arellano-Vázquez J.L., Gámez-Vázquez A.J. 2018. Tomato irregular ripening in the Culiacán Valley, Mexico. Rev. Fitotec. Mex., 41(3): 265-273. https://doi.org/10.35196/rfm.2018.3.265-273

- Azandémè-Hounmalon G.Y., Affognon H.D., Assogba Komlan F., Tamò M., Fiaboe K.K. M., Kreiter S., Martin T. 2015. Farmers' control practices against the invasive red spider mite, Tetranychus evansi Baker and Pritchard in Benin. Crop. Prot., 76(53): 58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2015.06.007

- Azandémè-Hounmalon G.Y., Sikirou R., Onzo A., Fiaboe K.K., Tamò M., Kreiter S., Martin T. 2022. Re-assessing the pest status of Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae) on solanaceous crops and farmers control practices in Benin. J. Agric. Food. Res., 10:100401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2022.100401

- Baker E.W., Pritchard A.E. 1960. The tetranychoid mites of Africa. Hilgardia. 29:455–574. https://doi.org/10.3733/hilg.v29n11p455

- Ben-David T., Melamed S., Gerson U., Morin S. 2007. ITS2 sequences as barcodes for identifying and analyzing spider mites (Acari: Tetranychidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol., 41:169-181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-007-9058-1

- Boubou A., Migeon A., Roderick G.K., Navajas M. 2011. Recent emergence and worldwide spread of the red tomato spider mite, Tetranychus evansi: genetic variation and multiple cryptic invasions. Biol. Invasions, 13:81-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-010-9791-y

- Chacón-Hernández J.C., Ordaz-Silva S., Mireles-Rodríguez E., Rocandio-Rodríguez M., López-Sánchez I.V., Heinz-Castro R.T.Q., Reyes-Zepeda F, Castro-Nava S. 2020. Resistance of wild chili (Capsicum annuum L. var. glabriusculum) to Tetranychus merganser Boudreaux. Southwest. Entomol., 45(1): 89-98. https://doi.org/10.3958/059.045.0110

- Da-Costa T., Couto M.A.M.S., Ferla J.J., Ferla N.J., Soares G.L.G. 2022. Report of Tetranychus evansi Baker & Pritchard (Acari: Tetranychidae) in species of the genus Nicotiana (Solanaceae). Entomol. Commun., 4: ec04042. https://doi.org/10.37486/2675-1305.ec04042

- Dayoub A.M., Dib H., Boubou A. 2022. Distribution and predators of the invasive spider mite Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae) in the Syrian coastal region, with first record of predation by the native Scolothrips longicornis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Acarologia, 62(3): 597-607. https://doi.org/10.24349/0k8s-gas6

- Delgado-Luna C., Cooper W., Villarreal-Quintanilla J.A., Hernández-Juárez A., Sánchez-Peña, S.R. 2023. Physalis virginiana as a wild field host of Bactericera cockerelli (Hemiptera: Triozidae) and Liberibacter solanacearum. Plant Dis., 3: PDIS02230350RE. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-02-23-0350-RE

- Doyle J.J., Doyle J.L. 1987. A rapid DNA isolation procedure from small quantities of fresh leaf tissues. Phytochem. Bull., 19: 11–15.

- EPPO. 2022. PM 7/116 (2) Tetranychus evansi. EPPO Bulletin, 52: 362-370. https://doi.org/10.1111/epp.12854

- Ferragut F., Escudero L.A. 1999. Tetranychus evansi Baker & Pritchard (Acari, Tetranychidae), una nueva araña roja en los cultivos hortícolas españoles. Bol. San. Veg. Plagas, 25: 157-164.

- Ferragut F., Garzón-Luque E., Pekas A. 2013. The invasive spider mite Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae) alters community composition and host-plant use of native relatives. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 60: 321-341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-012-9645-7

- Folmer O., Black W., Hoeh R., Vrijenhoek R. 1994. ADN primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol., 3(5): 294–299.

- Furtado I.P., Toledo S., de Moraes G.J., Kreiter S., Knapp M. 2007. Search for effective natural enemies of Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae) in northwest Argentina. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 43: 121-127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-007-9104-z

- Furtado I.P., de Moraes G.J., Kreiter S., Flechtmann C.H., Tixier M., Knapp M. 2014. Plant inhabiting phytoseiid predators of midwestern Brazil, with emphasis on those associated with the tomato red spider mite, Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Phytoseiidae, Tetranychidae). Acarologia, 54(4): 425-431. https://doi.org10.1051/acarologia/20142138

- Gotoh T., Araki R., Boubou A., Migeon A., Ferragut F., Navajas M. 2009. Evidence of co-specificity between Tetranychus evansi and Tetranychus takafujii (Acari: Prostigmata, Tetranychidae): comments on taxonomic and agricultural aspects. Int. J. Acarol., 35(6): 485-501. https://doi.org/10.1080/01647950903431156

- Guanilo A.D., de Moraes G.J., Toledo S., Knapp M. 2010. New records of Tetranychus evansi and associated natural enemies in northern Argentina. Syst. Appl. Acarol., 15(1): 3-20. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.15.1.1

- Knegt B., Meijer T.T., Kant M.R., Kiers E.T., Egas M. 2020. Tetranychus evansi spider mite populations suppress tomato defenses to varying degrees. Ecol. Evol., 10(10): 4375-4390. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6204

- Lugo-Sánchez M.A., Flores-Canales R.J., Isiordia-Aquino N., Lugo-García G.A, Reyes-Olivas Á. 2019. Tomato-associated phytophagous mites in northern Sinaloa, Mexico. Rev. Mexicana Cienc. Agric., 10(7): 1541-1550 https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v10i7.1756

- Mendonça R.S., Navia D., Diniz I.R., Flechtmann C.H. 2011. South American spider mites: new hosts and localities. J. Insect. Sci., 11: 121. https://doi.org/10.1673/031.011.12101

- Meynard C.N., Migeon A., Navajas M. 2013. Uncertainties in predicting species distributions under climate change: a case study using Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae), a widespread agricultural pest. PLoS One, 8(6): p.e66445. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066445

- Migeon A., Dorkeld F. 2023. Spider Mites Web: a comprehensive database for the Tetranychidae. Available from https://www1.montpellier.inrae.fr/CBGP/spmweb (Accessed 01/01/2024)

- Migeon A., Ferragut F., Escudero-Colomar L., Fiaboe K., Knapp M., de Moraes G.J., Ueckermann E., Navajas M. 2009. Modelling the potential distribution of the invasive tomato red spider mite, Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol., 48: 199–212. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-008-9229-8

- de Moraes G.J., McMurtry J.A. 1985. Comparison of Tetranychus evansi and T. urticae [Acari: Tetranychidae] as prey for eight species of phytoseiid mites. Entomophaga, 30:393-397. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02372345

- de Moraes G.J., McMurtry J.A. 1987. Effect of temperature and sperm supply on the reproductive potential of Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol., 3(2): 95-107. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01270471

- de Moraes G.J., McMurtry J.A., Baker E.W. 1987. Redescription and distribution of the spider mites Tetranychus evansi and T. marianae. Acarologia, 28(4): 333-343.

- Navajas M., de Moraes G.J., Auger P., Migeon A. 2013. Review of the invasion of Tetranychus evansi: biology, colonization pathways, potential expansion and prospects for biological control. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 59: 43-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-012-9590-5

- Ong S.N., Taheri S., Othaman R.Y., Teo C.H. 2020. Viral disease of tomato crops (Solanum lycopersicum L.): an overview. J. Plant. Dis. Prot., 127: 725-739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41348-020-00330-0

- Qureshi A.H., Oatman E.R., Fleschner C.A. 1969. Biology of the spider mite, Tetranychus evansi. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 62(4):898-903. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/62.4.898

- Reyes-Corral C.A., Cooper W.R., Karasev A.V., Delgado-Luna C., Sanchez-Peña S.R. 2021. ′Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum′ infection of Physalis ixocarpa Brot. (Solanales: Solanaceae) in Saltillo, Mexico. Plant Dis., 105(9): 2560-2566. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-10-20-2240-RE

- Santamaría M.E., Auger P., Martínez M., Migeon A., Castañera P., Díaz I., Navajas M., Ortego F. 2018. Host plant use by two distinct lineages of the tomato red spider mite, Tetranychus evansi, differing in their distribution range. J. Pest Sci., 91: 169-179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-017-0852-1

- Sarmento R.A., Lemos F., Bleeker P.M., Schuurink R.C., Pallini A., Oliveira M.G.A., Lima E.R., Kant M., Sabelis M.W., Janssen A. 2011. A herbivore that manipulates plant defence. Ecol. Lett., 14(3): 229-36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01575.x

- Savi P.J., de Moraes G.J., Melville C.C., Andrade D.J. 2019. Population performance of Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae) on African tomato varieties and wild tomato genotypes. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 77: 555-570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-019-00364-6

- Seeman O.D., Beard J.J. 2011. Identification of exotic pest and Australian native and naturalised species of Tetranychus (Acari: Tetranychus). Zootaxa, 2961: 1–72 https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2961.1.1

- SENASICA. 2017. Amplificación de la región mtDNA CO-I, para la identificación de insectos por PCR punto final LC01490/HC02198-SENASICA. Centro Nacional de Referencia Fitosanitaria, Dirección General de Sanidad Vegetal, Servicio Nacional de Sanidad, Inocuidad y Calidad Agroalimentaria. Mexico. https://docplayer.es/57829333-Amplificacion-de-la-region-mtadn-co-i-para-la-identificacion-de-insectos-por-pcr-punto-final.html. Accessed 5 December 2023.

- SIAP. 2023. Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera. Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Agrícola. Tomate (rojo). Available from: https://nube.siap.gob.mx/cierreagricola/. (Accessed 30/12/2023)

- Tsagkarakou A., Cros-Arteil S., Navajas, M. 2007. First record of the invasive mite Tetranychus evansi in Greece. Phytoparasitica, 35: 519-522. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03020610

- Wene G.P. 1956. Tetranychus marianae McG., a new pest of tomatoes. J. Econ. Entomol., 49: 712. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/49.5.712

2023-11-12

Date accepted:

2024-01-23

Date published:

2024-01-25

Edited by:

Migeon, Alain

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

2024 Monjarás-Barrera, José Irving and Sanchez-Peña, Sergio R.

Download the citation

RIS with abstract

(Zotero, Endnote, Reference Manager, ProCite, RefWorks, Mendeley)

RIS without abstract

BIB

(Zotero, BibTeX)

TXT

(PubMed, Txt)