Acaricide resistance in ticks from livestock farms in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Habeeba, Shameem  1

; Bensalah, Oum K.

1

; Bensalah, Oum K.  2

; Ibrahim, Ayman

2

; Ibrahim, Ayman  3

; Al Muhairi, Salama4

; Al Hammadi, Zulaikha

3

; Al Muhairi, Salama4

; Al Hammadi, Zulaikha  5

; Commey, Abraham

5

; Commey, Abraham  6

; Osman, Ebrahim

6

; Osman, Ebrahim  7

; Saeed, Meera8

and Shah, Asma

7

; Saeed, Meera8

and Shah, Asma  9

9

1✉ Veterinary Laboratories Division, Animal Wealth Sector, Abu Dhabi Agriculture and Food Safety Authority (ADAFSA), Abu Dhabi, UAE.

2Animal Health Division, Abu Dhabi Agriculture and Food Safety Authority (ADAFSA), Abu Dhabi, UAE.

3Policy and Regulatory Division, Abu Dhabi Agriculture and Food Safety Authority (ADAFSA), Abu Dhabi, UAE.

4Veterinary Laboratories Division, Animal Wealth Sector, Abu Dhabi Agriculture and Food Safety Authority (ADAFSA), Abu Dhabi, UAE.

5Veterinary Laboratories Division, Animal Wealth Sector, Abu Dhabi Agriculture and Food Safety Authority (ADAFSA), Abu Dhabi, UAE.

6Veterinary Laboratories Division, Animal Wealth Sector, Abu Dhabi Agriculture and Food Safety Authority (ADAFSA), Abu Dhabi, UAE.

7Animal Health Division, Abu Dhabi Agriculture and Food Safety Authority (ADAFSA), Abu Dhabi, UAE.

8Animal Health Division, Abu Dhabi Agriculture and Food Safety Authority (ADAFSA), Abu Dhabi, UAE.

9Veterinary Laboratories Division, Animal Wealth Sector, Abu Dhabi Agriculture and Food Safety Authority (ADAFSA), Abu Dhabi, UAE.

2024 - Volume: 64 Issue: 1 pages: 138-145

https://doi.org/10.24349/utkq-zek0Original research

Keywords

Abstract

Introduction

Ticks constitute a major threat to the livestock industry of the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) affecting the production of milk, meat, wool and hides (FAO, 2020). Productivity losses due to the voracious blood-feeding habit of ticks, injection of toxins, and transmission of pathogens such as Theileria spp. or Rickettsia spp. (Al-Deeb and Muzaffar 2020) have led to annual economic losses estimated at US 18.7 billion (Dzemo et al. 2022; Sungirai et al. 2018). These losses can be minimized by treating infected animals with acaricides. However, if poorly supervised, the application of acaricides can result in the emergence of resistance in ticks (FAO 2004; Rodriguez Vivas et al. 2007; Sharma et al. 2012).

Limited studies have been performed on the ticks and their associated host-parasite interactions in the Middle East region. Commonly available acaricides, like synthetic pyrethroids (cypermethrin and deltamethrin) and formamidines, are used indiscriminately for the control of ticks by livestock owners (Al-Deeb and Muzaffar 2020). In the Al Ain region (UAE), high tick loads by Hyalomma dromedarii, the most prevalent tick species in the region, have been reported on camels (Perveen et al. 2020), with up to 102 ticks/animal. To reduce infestations on camels, cypermethrin is the most commonly used acaricide (46.9% of camel owners), followed by diazinon (15.6%), α-cyper¬methrin (15.6%), fenvalerate (14.1%), and amitraz (Al-Deeb and Muzaffar 2020). H. dromedarii ticks were reported to be found on camels in a private farm in Al Ain over the entire year, despite monthly applications of an acaricide (Perveen et al. 2020), suggesting either the inadequate use of the acaricide or the development of acaricide resistance.

Diagnosing resistance to acaricides is performed primarily through bioassays, the most common being the adult immersion test (AIT) (Whitnall and Bradford 1947), the larval packet test (LPT) (Stone and Haydock 1962) and the larval immersion test (LIT) (Shaw 1966; Dzemo et al. 2022). The current study was undertaken to test for the development of resistance against cypermethrin in H. anatolicum in the Al Ain region using in vitro AIT bioassays and ticks collected from farms in the three regions of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi.

Material and Methods

Study Area

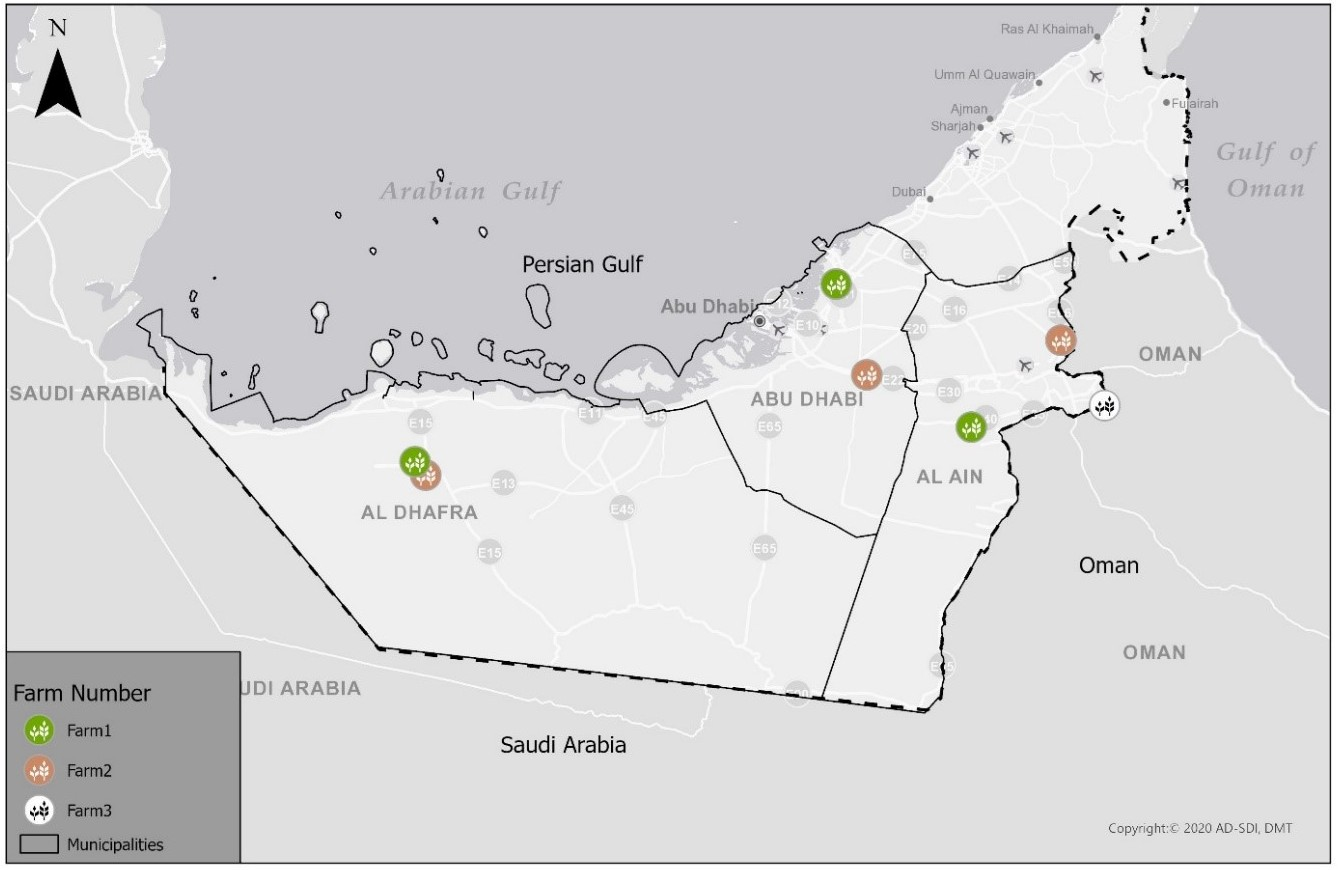

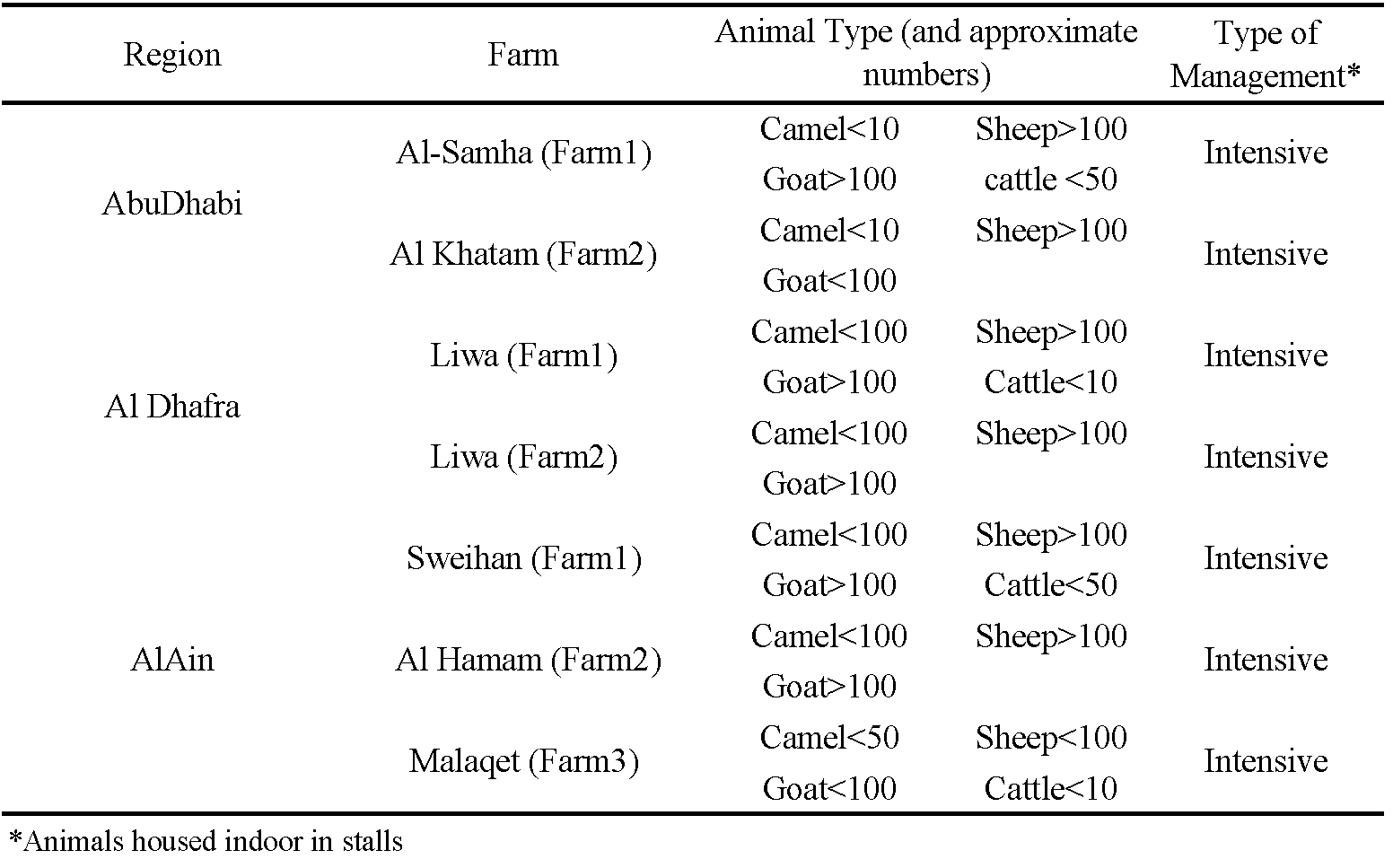

Abu Dhabi is located in the west and southwest part of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) along the southern coast of the Persian Gulf (Figure 1). The Emirate's high summer (June to August) temperatures are associated with high relative humidity and winters are relatively mild favouring tick survival. In 2020, a questionnaire was designed to collect data from 15 farm owners in three regions of Abu Dhabi related to the frequency, type, and mode of acaricide treatment adopted and their experiences on the efficacy of commonly used molecules (see supplementary materials). Ticks were then collected from seven of these farms based on questionnaire results (Table 1); we selected farms with mixed farming practices that had tick infestation problems and observed tick treatment failures. Hyalomma anatolicum was the most common tick collected from these farms based on morphology (Walker 2003) and was used for resistance studies. Live engorged female ticks were collected from naturally infested livestock in vials, closed with muslin cloth to allow air and moisture exchange, and were brought to the laboratory for experimental assays.

Adult Immersion Test (AIT)

Adult immersion tests were performed as per the method of Drummond et al. (1973) and Singh et al. (2014). The AIT uses engorged females that are immersed in solutions made with technical or commercial acaricides and compares oviposition rates between treated and untreated groups. The eggs can likewise be analysed by weight and viability. Female mortality rate can also be evaluated, which reduces the time necessary to obtain results (1–2 weeks) compared to the time required to determine hatchability (5–6 weeks). In our study, a total of 560 engorged adult female ticks of Hyalomma anatolicum were used and each drug concentration was replicated thrice using five adults each time along with a control group. Ticks weighing less than 150mg or that were not fully engorged were discarded. Selected fully engorged female ticks were immersed in different concentrations of cypermethrin (50 ppm, 100 ppm, 200 ppm, 400 ppm, 800 ppm) prepared from an aqueous dilution of a commercial preparation of cypermethrin (10.25% EC) for two minutes and then were dried on filter paper before transferring them into individually labelled plastic tubes. Ticks were placed in a constant climate chamber (Memmert HPP) at 28 ± 2 °C and 85 ± 5% relative humidity for a period of 14 days. Tick mortality was recorded on the 14th day post-treatment by observing the loss of mobility and pedal reflex after exposure to light. In this study, ticks which did not oviposit after 14 days were considered as dead as under optimal rearing conditions, the period of oviposition of engorged female ticks of H. a. anatolicum was recorded as a range of 7-12days (Anusha, 2014; Akil, M. et al., 2019).

Ticks collected from the same farm were treated on the same day with different drug concentrations along with a control (in distilled water) and data were recorded per farm. Observations on egg laying was performed 7-10 days post-treatment and egg mass was recorded on day 14. The reproductive index (RI) and the percent inhibition of oviposition for each acaricide concentration was calculated using the following formulae (Sharma et al. 2012).

\[ Reproductive~index~(RI) = \frac{egg~mass~weight}{engorged~female~weight} \]

\[ Percent~inhibition~of~oviposition~(IO\%) = \frac{RI~control - RI~treated}{RI~control} × 100 \]

Statistical Analysis

Dose response data were analyzed by the probit method (Finney 1962) using IBM SPSS Version 28.0.0.0. A Chi-square test was used to compare the observed mortality for each dose with the frequency predicted by the probit function. The LC50 and LC90 values for cypermethrin were determined by applying regression equations to the probit transformed mortality data.

Results and Discussion

As outlined above, mixed farms with heavy tick infestations and those for which pyrethroid acaricide treatment failure seemed to regularly occur were selected for the study based on results of the questionnaire (n=7 farms, Table 1). Tick infestations on these farms was observed throughout the year and tick-borne diseases were previously diagnosed, particularly in sheep and cattle. Camels were reared in the same area with sheep and goats, separated only by a small net fence. Keeping animals together in herds and on sandy floors were considered as potential risk factors for the presence of ticks. Indeed, local farms can provide a suitable refuge for ticks because they provide a habitat with relatively high moisture sheltered from the harsh desert environment (Al-Deeb and Muzaffar 2020).

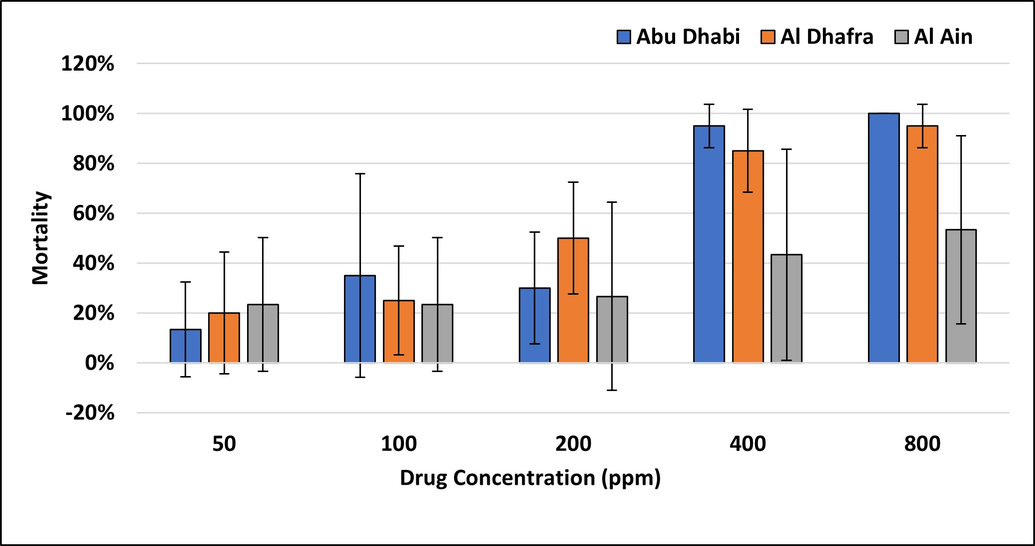

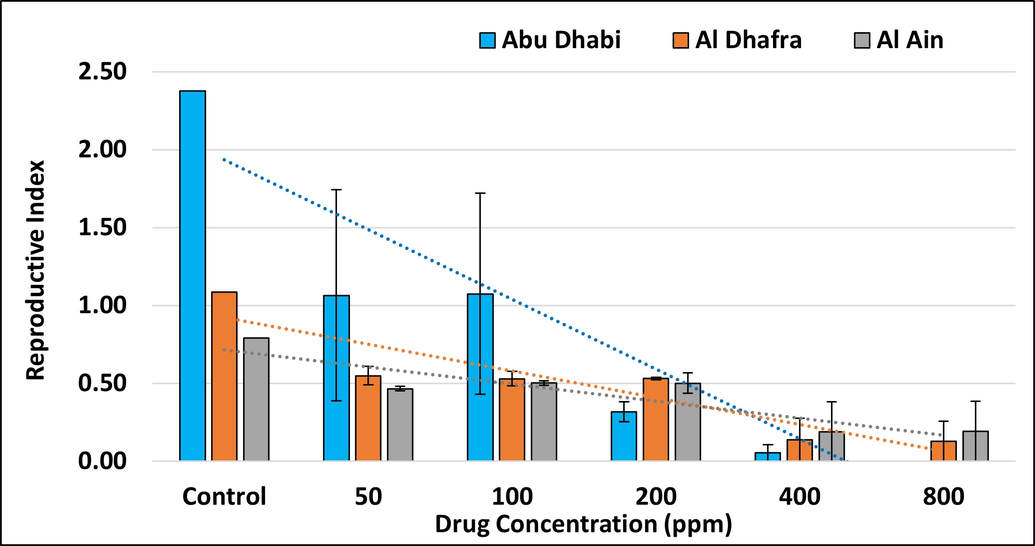

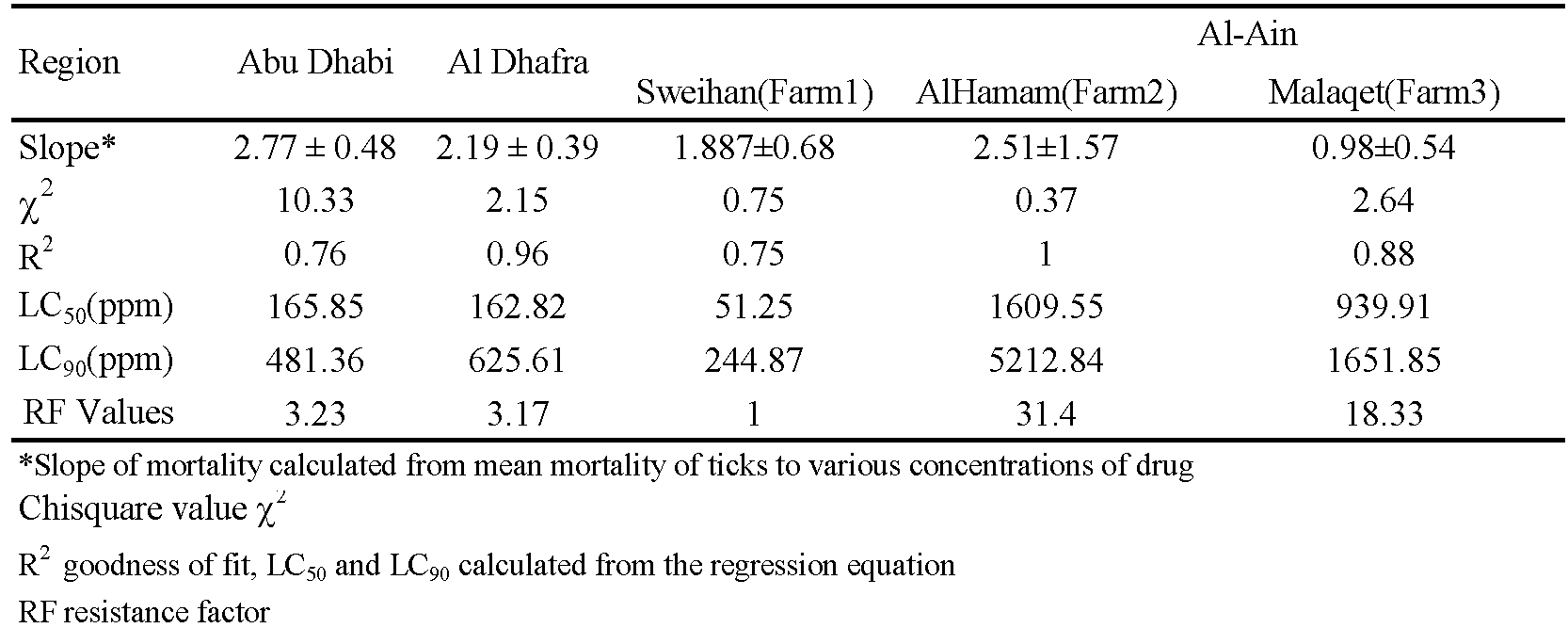

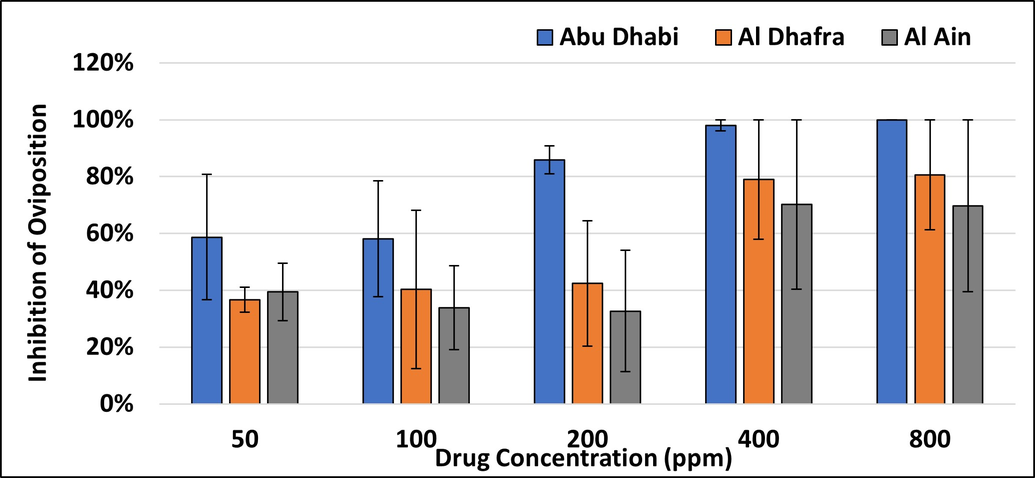

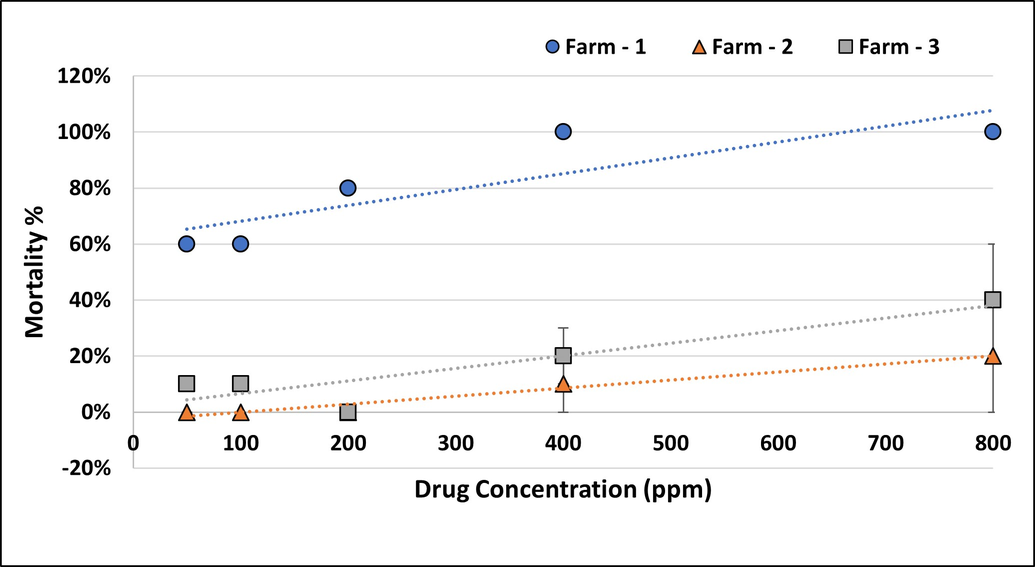

Tick populations have an immense potential for rapidly developing resistance due to their biological and behavioral characteristics, and resistance to different active ingredients has been reported in almost all countries where ticks occur (Alonso-Diaz et al. 2006). Synthetic pyrethroids are the most widely and frequently used acaricides to control tick populations. The present study aimed to detect acaricide resistance to the commonly used pyrethroid acaricide cypermethrin in field-collected Hyalomma anatolicum ticks from selected farms of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi. A concentration dependent increase in adult tick mortality was observed for cypermethrin in Abu Dhabi and Al Dhafra farms ,whereas this relationship was weaker in Al Ain farms (Figure 2). The reproductive index (RI) declined as drug concentration increased (Figure 3), with the strongest decline for ticks from Abu Dhabi farms. In contrast, the inhibition of oviposition increased with the cypermethrin dose (Figure 4) in all farms.

Among the three farms in Al Ain region, two farms namely Al Hamam (Farm2) and Malaqet (Farm3), showed low tick mortality at the tested doses and could not produce 100% mortality even at the highest concentration. (Figure 5). The reproductive indices were not affected and the percent inhibition of oviposition was less than 45% (Figures S1 and S2 in Supplementary Materials). These results indicate the acaricide resistance status of the ticks in these farms, with fully susceptible ticks present on farm 1 and very resistant ticks on farms 2 and 3.

The present study is the first of its kind in this region and throws some light on the resistance status of ticks against a frequently used acaricide. Abu Dhabi and Al Dhafra regions harbour tick populations that are heterogenous in terms of resistance, with LC90 values falling within the discriminating dose reported by earlier studies (Shyma et al. 2013). Hyalomma ticks from Sweihan (Farm 1 in Al Ain) were found to be susceptible to cypermethrin and the discriminating dose (2xLC90) was calculated as 489.74ppm in the present study.

Singh et al. (2014) classified resistance in ticks based on the calculated resistance factor (RF): susceptible (RF≤1.4), level I resistant (RF = 1.5–5.0), level II resistant (RF = 5.1–25.0), level III resistant (RF = 25.1–40) and level IV resistance (RF\textgreater40.1) in reference to a susceptible tick reference strain. Resistance factors (RF) for field tick samples were worked out by the quotient between LC50 of field ticks and LC50 of susceptible Sweihan H. anatolicum (Castro-Janer et al., 2009). Based on the regression analyses of the obtained data with the Sweihan isolate as the susceptible strain (Sharma et al. 2012; Shyma et al. 2012; Singh et al. 2014; Surbhi et al. 2018), the resistance factor (RF) was calculated to ascertain the susceptibility and resistant status of the other studied population. The Al Hamam isolates had Level III resistance, Al Malaqet isolates had Level II and the four farms in the Abu Dhabi and Dhafra regions showed Level I resistance (Table 2).

In the current study, the LC90 value of susceptible ticks (Sweihan population) by AIT bioassay was 244.87ppm, while it was over 5000ppm in the AlHamam farm of the same region. Much reported work on cypermethrin resistance has been conducted on Rhipicephalus microplus and a wide variation in LC90 values has been found. Singh et al. (2019) found an LC90 value of 183.07 ppm for R. microplus from the Jalandhar district of Punjab, India. Singh et al. (2015) reported level I resistance to cypermethrin in H. anatolicum collected from the Gujarat state, India using larval packet test. Sharma et al. (2012) found a LC50 value of cypermethrin of 138.5 ppm with a 95% confidence interval of 134.5–142.6, while the LC95 value was 349.1 ppm with a 95% confidence interval of 323.2–377.0 using a laboratory reared susceptible line of R. microplus in Izatnagar, India. This variance among studies has been attributed to differences in the reference tick lines used and in the type of bioassay adopted (AIT or LPT) (FAO 2004; Robertson et al. 2006; Castro-Janer et al. 2009; Aguirre et al. 2000; Jonsson et al. 2007; Klafke et al. 2017).

This study forms the first report on acaricide resistance in ticks of the UAE. A country specific discriminating concentration (DC = two times the concentration that would kill 99% of ticks susceptible to the molecule) was not previously available for any tick species, hence the generation of baseline data for an abundant tick species is useful for monitoring changes in the resistance status of ticks in this Emirate. Here, we calculated the DC for commercially available cypermethrin as 489.74 ppm for Hyalomma anatolicum. This DC can now be used as a screening mechanism because one can test for resistance in small samples from diverse locations (FAO 2004).

The development of resistance in a tick population can depend on factors related to acaricide use, ecological niches and the genus of ticks involved (Kunz and Kemp 1994; Singh et al. 2019). A limitation in the present study was the difficulty in obtaining adequate numbers of engorged females for testing, which may affect the reproducibility of AIT values (Jonsson et al. 2007). Further studies with higher sample sizes are recommended to obtain more predictive values of AIT. Similarly, a commercial formulation of cypermethrin was used in the present study as the pure technical grade was unavailable. The presence of proprietary ingredients in commercial formulations can hinder the responses to active ingredients (Shaw 1966) which could alter the results and might be one of the reason for the relatively high LC90 value that we found. Tests based on technical grade cypermethrin would therefore be useful to validate our results. The frequent use of acaricides leading to the emergence of resistant population, as observed in our results, likely explains the presence of ticks on treated animals as reported by Perveen et al. 2020. The present study reported only Hyalomma spp. ticks in the farms in the region. Based on morphological characteristics,only Hyalomma anatolicum (90%) and H. dromedarii (10%) were identified (Walker 2003). The practice of rearing camels with sheep and goats and mixing them on common grazing habitats likely increases the risk of ticks shifting among alternative hosts. Moreover, local farms provide suitable environments for ticks, with sand beds in which ticks can burrow a few centimeters below ground and find both favorable microhabitats for egg deposition and refuge from the chemical spraying. Improper use of acaricides in terms of dose, frequency and method of application can thus result in acaricide failure. Based on the data obtained on the emerging problem of tick resistance to chemical acaricides, an alert on good practices for tick control to improve the drug efficacy is recommended, along with the implementation of a program to monitor the evolution of acaricide resistance.

Acknowledgements

The project investigators thank the veterinary officers Ashry Mohammed Ahmed, Raid Mohammed, Francis Falcon Joven, Atef Darwish, Ibraheem Ghazi, Mohamed Ibrahim Hassanein, Mahmud Hamed Abd Elaal, Manoj Shrawan Pradhan, the livestock and animal health assistants, the herders from the study areas and, the laboratory personnel for their support in the execution of the presented research.

acarologia_4679_SupplementaryMaterials.docx

References

- Aguirre D.H., Vinabal A.E., Salatin A.O., Cafrune M.M., Volpogni M.M., Mangold A.J., Guglielmone A.A. 2000. Susceptibility to two pyrethroids in Boophilus microplus (Acari: Ixodidae) populations of north-west Argentina. Preliminary results. Vet. Parasitol., 88:329-334.

- Alonso-Diaz M.A., Rodriguez-Vivas R.I., Fragoso-Sanchez H., Rosario-Cruz R. 2006. Resistance of the Boophilus microplus tick to ixodicides. Arch. Med. Vet., 38:105-114. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0301-732X2006000200003

- Al-Deeb M.A., Muzaffar S.B., Abu Zeid Y., Enan M.R. and Karim S. 2015. First record and prevalence of Rickettsia sp. and Theileria annulata in Hyalomma drom¬edarii (Acari: Ixodidae) ticks in the UAE. Fla. Entomol., 98: 135-139.

- Al-Deeb M.A., Muzaffar S.B. 2020. Prevalence, distribution on host's body, and chemical control of camel ticks Hyalomma dromedarii in the United Arab Emirates. Vet. World., 13:114-120. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2020.114-120

- Akil M., Bagherwal R.K., Jayraw A.K., Rajput N. and Singh R. 2019. In vitro Assessment of Period of Oviposition and Hatching in Hyalomma anatolicum anatolicum. Ind J Vet Sci and Biotech., 15: 72-73. https://doi.org/10.21887/ijvsbt.15.2.19

- Anusha M. 2014. PCR evaluation for detection of Theileria annulata and Hyalomma anatolicum anatolicum ticks in Rayalaseema region of Andhra Pradesh. M.V.Sc. And A.H thesis. Shree Venkateshwara Veterinary University, Tirupati, India.

- Castro-Janer E., Rifran L., Piaggio J., Gil A., Miller R.J., Schumaker T.T.S.2009. In vitro tests to establish LC50 and discriminating concentrations for fipronil against Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus (Acari: Ixodidae) and their characterization. Vet. Parasitol., 162:120-128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.02.013

- Dzemo W D., Thekisoe O., Vudriko P. 2022. Development of acaricide resistance in tick populations of cattle: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 8: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08718

- Drummond R.O., Ernst S.E., Trevino J.L., Gladney W.J., Graham O.H. 1973. Boophilus annulatus and Boophilus microplus: laboratory test of insecticides. J. Econ. Entomol., 66: 130-133. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/66.1.130

- FAO. 2004. Resistance Management and Integrated Parasite Control in Ruminants. Guidelines. Animal Production and Health Division. FAO. p. 25-77.

- FAO. Livestock Systems. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/livestock-systems/en/

- Finney D.J.1962. Probit Analysis - A Statistical Treatment of the Response Curve.

- Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.pp. 318.

- Jonsson N.N., Miller R.J., Robertson J.L.2007. Critical evaluation of the modified-adult immersion test with discriminating dose bioassay for Boophilus microplus using American and Australian isolates. Vet. Parasitol., 146:307-315.

- Klafke G., Webster A., Agnol B.D., Pradel E., Silv J., Henrique de La Canal L., Becker M., Os_orio M.F., Mansson M., Barreto R., Scheffer R., Souza U.A., Corassini V.B., dos Santos J., Reck J., Martins J.R. 2017. Multiple resistance to acaricides in populations of Rhipicephalus microplus from Rio Grande do Sul state, Southern Brazil. Ticks Tick Borne Dis., 8: 73-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.09.019

- Kunz S.E., Kemp D.H.1994. Insecticides and acaricides: resistance and environmental impact. Rev. Sci. Tech. OIE. 13: 1249-1286. https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.13.4.816

- Perveen N., Bin Muzaffar S., Al-Deeb M.A.2020. Population dynamics of Hyalomma dromedarii on camels in the United Arab Emirates. Insects. 11: 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11050320

- Robertson J.L., Russell R.M., Preisler H.K., Savin N.E.2006. Pesticide Bioassays with Arthropods, 2nd ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA. pp.224. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420004045

- Rodriguez Vivas R.I., Rivas A.L., Chowell G., Fragoso S.H., Rosario C.R., Garcııˇa V.Z., Smith S.D., Williams J.J., Schwager S.J. 2007. Spatial distribution of acaricide profiles (Boophilus microplus strains susceptible or resistant to acaricides) in south-eastern Mexico. Vet. Parasitol., 146:158-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.01.016

- Sharma A.K., Rinesh Kumar, Sachin Kumar, Gaurav Nagar, Nirbhay K.S., Sumer S.R., Dhakad M.L., Rawat A.K.S., Ray D.D., Srikant G. 2012. Deltamethrin and cypermethrin resistance status of Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus collected from six agro-climatic regions of India. Vet. Parasitol., 188: 337- 345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.03.050

- Shaw R.D.1966. Culture of an organophosphorus resistant strain of Boophilus microplus (Canestrini) and assessment of its resistance spectrum. Bull. Entomol. Res., 56:398-405. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485300056480

- Shyma K.P., Kumar S., Sharma A.K., Ray D.D., Ghosh S. 2012. Acaricide resistance status in Indian isolates of Hyalomma anatolicum. Exp. App. Acarol., 58:471-81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-012-9592-3

- Shyma K.P., Kumar S.A., Sangwan A.K., Sharma A.K., Nagar G., Ray D.D.2013. Acaricide resistance status of Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) micro plus and Hyalomma anatolicum collected from Haryana. Ind. J. Anim. Sci., 836:591-4. https://epubs.icar.org.in/index.php/IJAnS/article/view/30624

- Singh N.K., Rath S.S. 2014. Esterase mediated resistance against synthetic pyrethroids in field populations of Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus (Acari: Ixodidae) in Punjab districts of India. Vet. Parasitol., 204: 330-338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.05.035

- Singh N.K., Jyoti., Nandi, A., Singh H. 2019. Detection of Multi-Acaricide Resistance in Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) Microplus (Acari: Ixodidae). Explor. Anim. Med. Res., 9: 24-28.

- Stone B.F., Haydock P., 1962. A method for measuring the acaricide susceptibility of the cattle tick Boophilus microplus (Can.). Bull. Entomol. Res., 53:563-578. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000748530004832X

- Sudha R.R., Placid ED'Souza., Byregowda S.M., Veeregowda B. M., Sengupta P.P., Chandranaik B.M.,Thimmareddy P.M. 2018. In vitro acaricidal efficacy of deltamethrin, cypermethrin and amitraz against sheep ticks in Karnataka. J. Entomol. and Zoology Studies. 6: 758-762.

- Sungirai M., Baron S., Moyo D.Z., De Clercqe P., Maritz-Olivier C., Madder M.2018. Genotyping acaricide resistance profiles of Rhipicephalus microplus tick populations from communal land areas of Zimbabwe. Ticks Tick Borne Dis., 9: 2-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.10.017

- Surbhi., Snehil G., Arun K.S., Nirmal S.2018. Synthetic pyrethroids and Amitraz resistance in Hyalomma anatolicum ticks of Sirsa district, Haryana. The Pharma Innovation Journal. 7: 576-578.

- Walker A.R. 2003. Ticks of Domestic Animals in Africa: A Guide to Identification of Species. Bioscience Reports, Edinburgh. pp. 227.

- Whitnall A.B., Bradford B. 1947. An arsenic resistant tick and its control with gammexane dips. Bull. Entomol. Res., 38: 353-372. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000748530002424X

2022-09-01

Date accepted:

2023-12-29

Date published:

2024-01-17

Edited by:

McCoy, Karen

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

2024 Habeeba, Shameem; Bensalah, Oum K.; Ibrahim, Ayman; Al Muhairi, Salama; Al Hammadi, Zulaikha; Commey, Abraham; Osman, Ebrahim; Saeed, Meera and Shah, Asma

Download the citation

RIS with abstract

(Zotero, Endnote, Reference Manager, ProCite, RefWorks, Mendeley)

RIS without abstract

BIB

(Zotero, BibTeX)

TXT

(PubMed, Txt)