How the plant probiotic bacteria and herbivore-induced plant volatiles (HIPVs) alter functional response of Phytoseiulus persimilis (Phytoseiidae) on the two-spotted spider mite

Montazersaheb, Hosna1

; Zamani, Abbas Ali  2

; Sharifi, Rouhallah

2

; Sharifi, Rouhallah  3

and Darbemamieh, Maryam

3

and Darbemamieh, Maryam  4

4

1Department of Plant Protection, College of Agriculture, Razi University, Kermanshah, Iran.

2✉ Department of Plant Protection, College of Agriculture, Razi University, Kermanshah, Iran.

3Department of Plant Protection, College of Agriculture, Razi University, Kermanshah, Iran.

4Department of Plant Protection, College of Agriculture, Razi University, Kermanshah, Iran.

2023 - Volume: 63 Issue: 3 pages: 834-843

https://doi.org/10.24349/a9ak-1wu2Original research

Keywords

Abstract

Introduction

The two spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch. (Acari: Tetranychidae), is an economically important pest worldwide that can cause significant damage to a variety of crops. Its feeding results in pale spots on the leaves, reduced photosynthesis, leaf fall and potentially plant death (Migeon and Dorkeld 2010). The short generation length of T. urticae leads to rapid resistance development against several acaricides, making the use of biological control agents increasingly popular (McMurty and Croft 1997).

The predatory mite, Phytoseiulus persimilis Athias-Henriot (Acari: Phytoseiidae) is a biocontrol agent of T. urticae (McMurtry, 1982). They explore the environment and seek their prey primarily by olfactory information because they lack eyes (Sabelis and van der Baan 1983). T. urticae induces different herbivore-induced plant volatiles (HIPVs) in different host plants due to its highly polyphagous nature. As a result, P. persilimis, its predator, can distinguish the prey between different HIPVs (Dicke et al. 1998).

Plants respond to herbivore damage through various direct and indirect mechanisms (Kessler and Baldwin 2001). Increased plant resistance to insects is referred to as a direct defense, whereas the release of volatile cues is an indirect defense (Rasmann and Agrawal 2009). These volatiles, commonly known as HIPVs, play multiple roles in interactions with other plants and animals. One of these roles is helping natural enemies to find their herbivore prey or host (Dicke et al. 1999). HIPVs consist of various low molecular weight chemical volatiles, and are mainly produced by three major pathways including the jasmonic acid, salicylic acid and ethylene pathways. Methyl jasmonate (MeJa) and methyl salicylate (MeSa) are two important volatile compounds synthesized via the jasmonic acid and salicylic acid pathways, respectively (De Boer and Dicke 2004; Wasternack and Parthier 1997). Methyl jasmonate is a critical cellular regulator that activates plant defense mechanisms in response to insect feeding, pathogens, and environmental stresses (Wasternack and Parthies 1997). Methyl salicylate is a HIPV found in at least 13 plant species, including beans, when spider mites injure them, and it is appealing to predatory mite P. persimilis (James 2003; Van Den Boom et al. 2004; Dicke and Sabelis 1988). Plants develop defensive mechanisms in response to 3-pentanol (Choi et al. 2014), while indole is produced when the plant is attacked or receives signals from other plants under attack. It attracts natural enemies of the plant infesting herbivores (Cna′ani et al. 2018).

Plant probiotic bacteria (PPB) are plant-associated microorganisms that can cause the plant to develop resistance against herbivores (van Loon et al., 2004). One of the most important and extensively studied genera of PPB is Bacillus spp., which can colonize the roots of plants and act as a biofertilizer or biopersticide (Glick 1995). The plant probiotic bacteria Bacillus pumilus strain INR7 (Bacillales: Bacillaceae) and Bacillus velezensis strain Fol (Bacillales: Bacillaceae) can produce volatile compounds with growth-promoting effects (Kloepper and Ryu 2006; Zhuang et al. 2007). The predatory mite, P. persimilis can use HIPVs to locate its prey. It has been shown that P. persimilis is highly sensitive to specific HIPVs, such as methyl salicylate and (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate, which are commonly produced by plants under herbivore attack. The mite can detect these chemicals at very low concentrations and use them to locate their prey accurately (Dicke et al. 1990; War et al. 2011).

As a result, we may be able to employ these volatiles and PPB, which produces volatiles, to support P. persimilis in locating T. urticae. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the effect of methyl jasmonate, methyl salicylate, indole, 3-pentanol, B. pumilus INR7, and B. velezensis FOL on the functional response of P. persimilis to the two-spotted spider mite, using kidney bean, Phaseolous vulgaris L., attached leaves. We used these volatile compounds and bacteria to determine whether they could affect the functional response of P. persimilis. The use of these treatments could improve the efficiency and effectiveness of biological control strategies for managing pest mite populations.

Material and methods

Host plant, mite and predator

Phaseolous vulgaris seeds of Derakhshan variety were sterilized using a one percent sodium hypochlorite solution. They were then planted in 15 cm diameter pots with a height of 20 cm filled with equal proportions of autoclaved field soil, perlite, and peat moss. These pots were kept in climate-controlled rooms (25 ± 2 °C, 65 ± 5% relative humidity and a photoperiod of 16L:8D h). A population of T. urticae which was originally collected from a research greenhouse located in the Campus of Agricultural and Natural Resources, Razi University, was inoculated on these bean plants after two weeks, and they were kept under the same laboratory conditions for two months.

A colony of P. persimilis was obtained from Koppert Biological System (Spidex®) and grown on T. urticae-filled kidney bean leaves placed on plastic sheets on water-soaked foams. These foams were placed in half-filled plastic boxes with water. New kidney bean leaves containing prey were added to this arena daily. The edges of plastic sheets were covered with moist tissue papers and stored in laboratory settings for two months to prevent predators from escaping and kept for two months in laboratory conditions (25 ± 2 °C, 65 ± 5% relative humidity and a photoperiod of 16L: 8D h) (Walzer and Schausberger 1999). This population was used as a stock colony.

The plant probiotic bacteria

Bacillus pumilus INR7 were kindly provided by J.W. Kloepper (Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama). Bacillus velezensis FOL was obtained from the culture collection of the Department of Plant Protection, College of Agriculture, Razi University.

Both of these Bacillus strains were cultivated in nutrients broth for 48 hours at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C), with constant shaking at 150 rpm. Then, the bacterial suspension was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 20 minutes and the pellet was suspended in physiological saline. The bacterial concentration was adjusted to 109 CFU mL(-1) was later used as a bacterial inoculum. P. vulgaris cv Derakhshan germinated seeds were sterilized and soaked in 5 mL of this bacterial suspension for 30 minutes before being planted in 14 cm tall plastic pots with an 18 cm diameter. These pots were filled with an equal mixture of sterilized field soil, sand, and peat moss and kept in a growth chamber (25 ± 1 °C, 65 ± 5% relative humidity and a photoperiod of 16L: 8D h).

The herbivore induced plant volatiles treatments

A concentration of 100 µM methyl salicylate, methyl jasmonate, indole and 3-pentanol were prepared in 0.02% Tween 20. Sterilized germinated seeds of P. vulgaris cv. Derakhshan were separately soaked in these emulsions for an hour and planted in pots of 14 cm in height and 18 cm in diameter afterward. The plants soaked in 0.02% Tween 20 served as the control group. The pots of each treatment were kept in separate growth chambers (25 ± 1 °C, 65 ± 5% relative humidity and a photoperiod of 16L: 8D h). After ten days, the young plants were sprayed with five mL of each HIPV emulsion. The plants were ready for functional response experiments the next day.

Functional response

A population of 100 P. persimilis females were randomly selected and transferred to a new arena to obtain a same-aged predator colony. The predatory mites were allowed to lay eggs for 24 hours, then removed from the arena. These arenas were kept in a growth chamber (25 ± 1 °C, 65 ± 5% relative humidity and a photoperiod of 16L: 8D h) and monitored daily. Newly emerged female adults were transferred to the new arena and starved for one day. These 1-day-old adult female individuals were used for functional response experiments.

The experimental unit was a 3.5 cm diameter petri dish placed on the lower side of an attached kidney bean leaf. During 24 hours, the 1-day-old adult female individuals of P. persimilis were given eight densities (2, 5, 10,20,30,40,50 and 60) of T. urticae eggs in ten replications. Gravid females of T. urticae were transferred to the leaves, allowed to oviposit for 24 hours, and then removed to simulate natural conditions (such as the existence of web and egg placement). The placed eggs were tallied on each leaf, and if the number was too high or low, some eggs were removed or added, respectively. One 1-day-old adult female individual of P. persimilis was added to each replication from the same aged colony, and the predators were removed after 24 hours. The intact remaining eggs were counted afterward.

Data analysis

The functional response data were analyzed in two steps (Juliano 2001). In the first step, we used logistic regression of the proportion of prey consumed (Ne/N0) as a function of initial density (N0) to determine the type of functional response.

\[\frac{N_e}{N_0} = \frac{exp(P_0+P_1 N_0+P_2 N_0^2+P_3 N_0^3)}{(1+exp(P_0+P_1 N_0+P_2 N_0^2+P_3 N_0^3)} (1)\]

Where (Ne/N0 ) represents the probability that a prey will be consumed, and P0 , P1 , P2 and P3 are the intercepts, linear, quadratic and cubic coefficients, respectively, estimated using the maximum likelihood method (Xiao and Fadamiro 2010). The type of functional response was determined by fitting the data to model (1). If the function is negative (P1\textless0), the functional response is type II, which means that the amount of consumed prey, decreases monotonically as the number of prey increases. The predator displays a type III functional response if the function is positive(P1\textgreater0 and P2\textless0) (Juliano 2001). The predator displays a type III functional response, if the function is positive. In the second step, the handling time (Th ) and the attack rate (a) coefficients of a type II response were estimated using an explicit deterministic model in the second stage (Royama 1971; Rogers 1972).

\[N_e = N_1 [1-exp(a(T_h N_a-T))] (2)\]

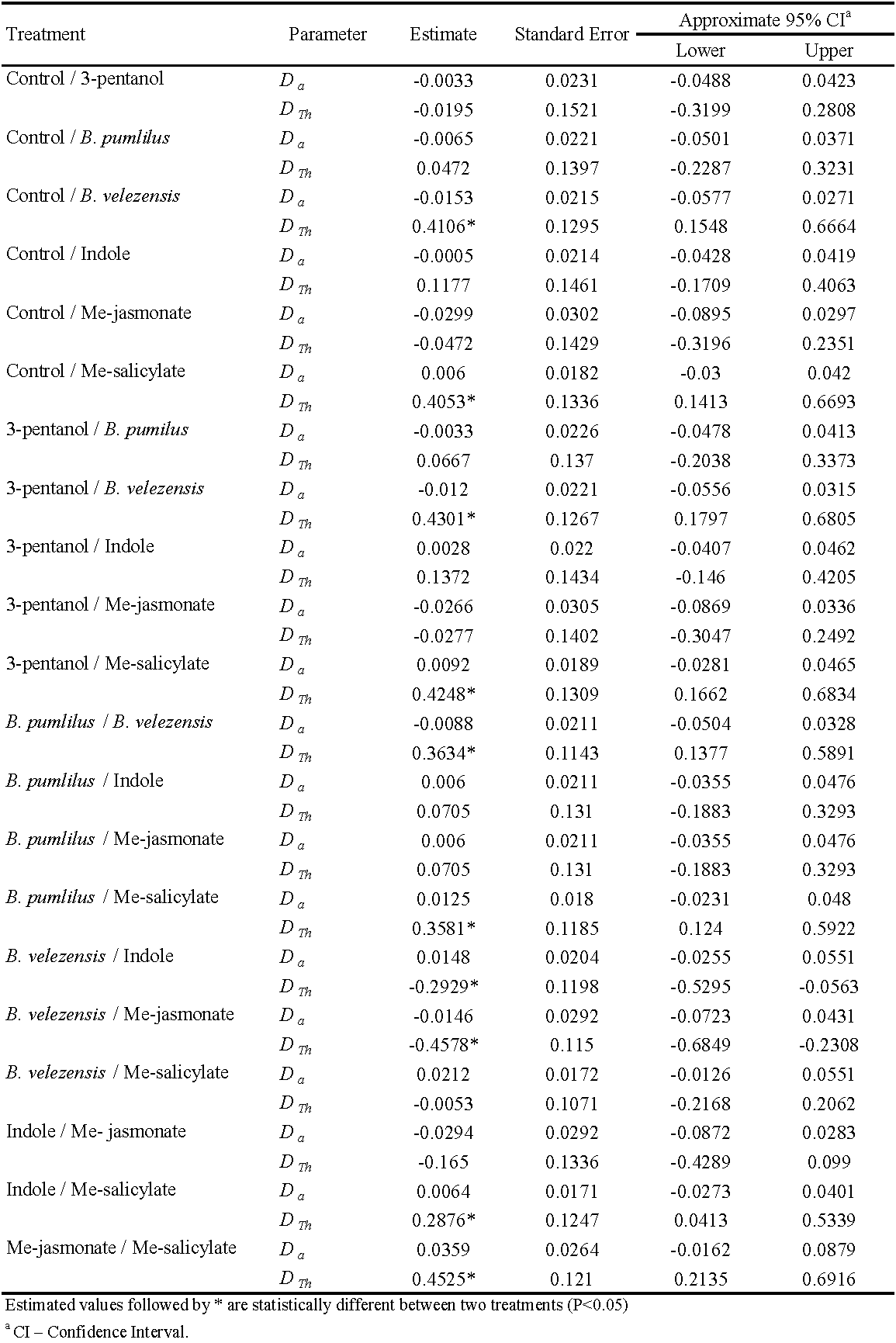

Where Ne is the number of preys consumed; N0 is the initial number of preys; Th is the handling time, and T is the predator's total time. Statistical paired comparisons of the parameters of the functional responses for different treatments and the control were performed using the indicator variable method (Juliano 2001).

\[N_a = N_0 \{1-exp[-(a+(D_a (j))(T-(T_h+D_Th (j)) N_a )]\} (3)\]

Where j is an indicator variable with a value of 0 for the first data series and 1 for the second data series. The parameters Da and DTh estimate the differences between the values of the parameters a and Th , respectively, of the data sets being compared. The null hypothesis that DTh comprises 0 is tested to see if there is a substantial difference between the two treatments (Juliano 2001). The data were analyzed using SAS software (SAS 9.4). Finally, using the predicted Th , the maximum predation rate (T/Th ) was computed, which represents the maximum number of prey that a predator can consume in 24 hours (Hassell 2000).

Results

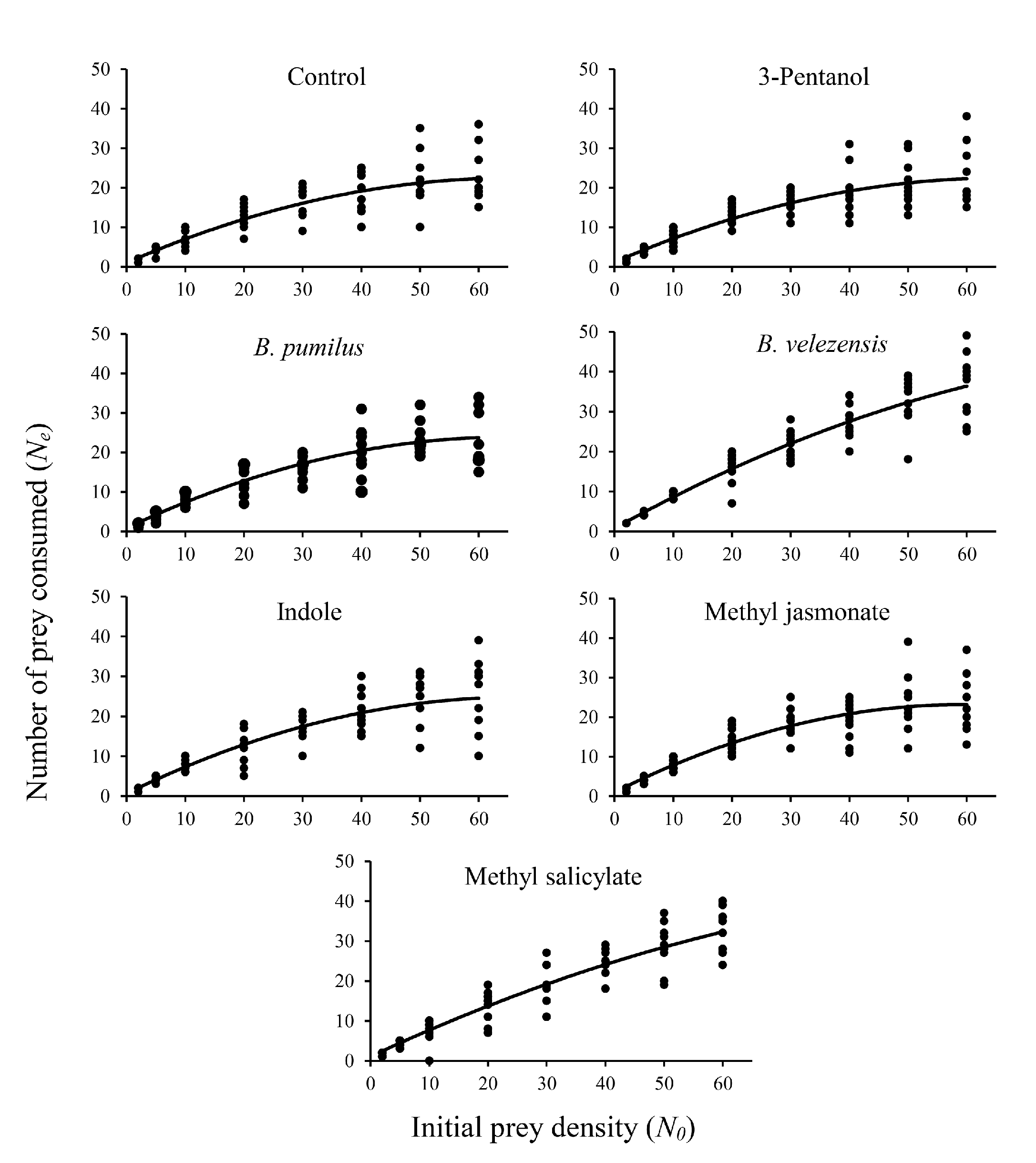

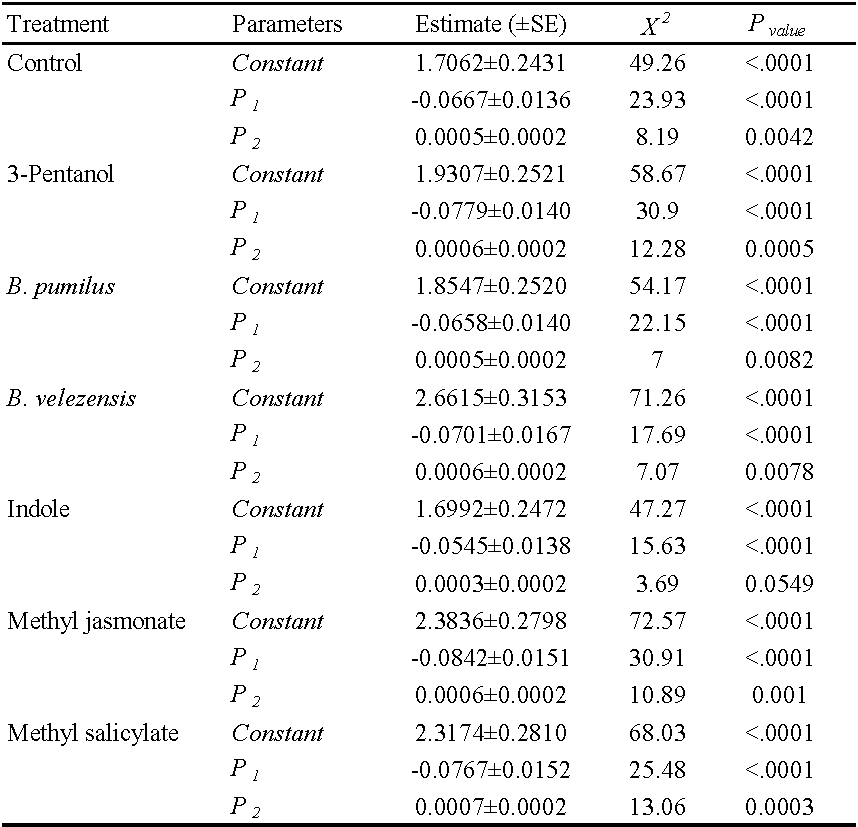

Figure 1 shows the functional response of 1-day-old P. persimilis females fed on different densities of T. urticae eggs on treated and untreated bean plants. The logistic regression analysis results indicated that the linear coefficient was negative (P1 < 0) in all cases, indicating a type II functional response (Table 1). According to the results, the proportion of eggs consumed by P. persimilis of the initial egg density (Ne/N0) decreased as prey density increased (Figure 1).

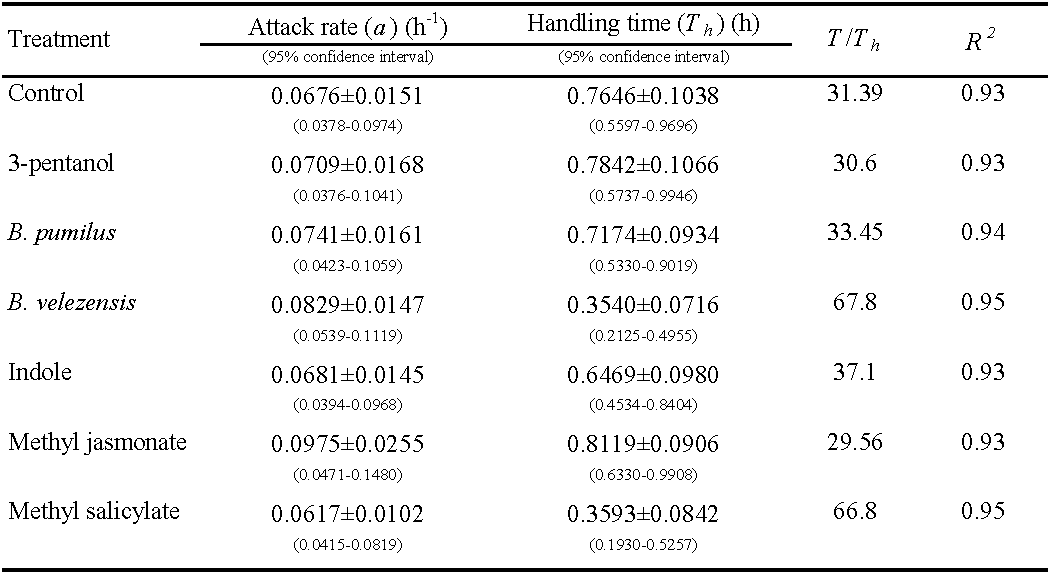

The linear coefficient of equation (1) on different treatments was negative and significantly different from 0 (P \textless0.01), indicating that P. persimilis exhibited a type II response to T. urticae in all treatments. The predation rate increased at a declining rate (Table 1). The estimated attack rate (a) and handling time (Th ) of P. persimilis on different treatments are presented in Table 2. The predatory mite, P. persimilis attack rates ranged from 0.0617 h-1 on methyl salicylate to 0.0975 h–1 on methyl jasmonate. The estimated handling times ranged from 0.3540 ± 0.0716 h on B. velezensis to 0.8119 ± 0.0906 h on methyl jasmonate.

Discussion

One of the best ways to reduce the harmful effects of pesticides in agriculture is to replace them with environmentally friendly methods. One such method is the use of natural enemies. However, some may not function properly, necessitating measures to improve efficiency. One of these methods is using herbivore-induced plant volatiles and plant probiotic bacteria. This study investigated the effect of certain HIPVs and PPB on the functional response of P. persimilis fed for the first time on T. urticae eggs attached to kidney bean leaves. Keeping the leaves attached to the plant can increase the similarity between the experimental and natural conditions.

This study revealed that the functional response of P. persimilis on T. urticae eggs laid on P. vulgaris treated with different HIPVs (3-pentanol, indole, methyl jasmonate and methyl salicylate) and PPB (B. pumilus and B. velezensis) was type II, and the proportion of killed prey decreased as prey density increased. Some previous studies also reported a type II functional response for phytoseiid mites (Cedola et al. 2001; 2004, Xiao and Fadamiro 2010; Farazmand et al. 2012; Seiedy et al. 2012). The findings from our study are consistent with those of Sznajder et al. (2010), who investigated the response of P. persimilis to methyl salicylate on plants attacked by the two-spotted spider mite. Both studies found that plant volatiles play an important role in the foraging behavior of P. persimilis. Additionally, Sznajder et al. (2010) found genetic variation in the response to methyl salicylate among iso-female lines of P. persimilis. However, in contrast to our study, Sznajder et al. (2010) focused on the effect of methyl salicylate alone, while we investigated the effect of HIPVs and PPB on the functional response of P. persimilis. Our study expands upon these findings and demonstrates that certain HIPVs and PPB can reduce the predator's handling time, indicating that these methods have the potential to improve the efficiency of P. persimilis in controlling T. urticae.

There was no significant change in attack rate (a) versus encounter rate with prey across all treatments. Handling time (Th ) includes all time spent resting, searching, and occupied with the prey while unable to attack other prey (Gurevitch and Hedges 2001). The handling time on the B. velezensis (0.3540 ± 0.0716 h) and the methyl salicylate (0.3593 ± 0.0842 h) treatments, was significantly lower than other treatments (P\textless0.05). In both B. velezensis and methyl salicylate treatments, the predatory mite had the highest amount of feeding at the highest egg density (Figure 1), which confirms the reduction of handling time in these treatments. The highest value of the estimated maximum predation rate (T/Th ) over 24 hours was recorded as 67.80 prey per day for B. velezensis and 68.80 prey per day for methyl salicylate due to their shorter handling time compared to the other treatments and control.

It was discovered that P. persimilis favored a volatile mixture containing methyl salicylate (produced by T. urticae) over similar compounds having methyl jasmonate instead of methyl salicylate (De boer and Dicke 2003). Furthermore, adding methyl salicylate to a methyl salicylate-free blend significantly increased the mite's odor preference. This study suggested that methyl salicylate plays a vital role as a signal to the foraging mites. Our results showed that methyl salicylate could decrease the predator's handling time. This could be related to increased olfactory stimulants, which aid in faster prey detection.

Reducing the size of T. urticae eggs due to using methyl salicylate and B. velezensis is another possibility for reducing the handling time of these treatments. Smaller eggs may be easier for the predator to capture and manipulate, as they may require less manipulation and processing by the predator's mouthparts. Additionally, smaller eggs may provide a higher surface area to volume ratio, which could make them easier for the predator to digest, potentially reducing the time required to process and assimilate the nutrients contained in the eggs. Our previous study showed that among 3-pentanol, indole, methyl jasmonate, and methyl salicylate, B. pumilus and B. velezensis, two of them (methyl jasmonate and B. velezensis) could decrease the intrinsic rate of increase (r) for T. urticae (Montazersaheb et al. 2021). Thus, these two have the most detrimental effect on the development of T. urticae. Hence, they may decrease the size of the eggs.

Methyl salicylate could induce direct and indirect defense mechanisms (Fang et al. 2015). Methyl salicylate can also trigger the plant's HIPVs production, increasing plant defense (Khan et al. 2008). More robust plant defense could have a negative effect on the growth and development of T. urticae, resulting in smaller eggs. The smaller eggs take less time for the predatory mite to eat. Therefore, the handling time will be improved in these treatments. The handling time in methyl salicylate treatment was significantly lower than 3-pentanol, B. pumilus, indole, and methyl jasmonate.

Previous studies have shown that plant probiotic bacteria belonging to the genus Bacillus increase several plants' biomass and root length (Meng et al. 2016; Madhaiyan et al. 2010). Increasing plant biomass is one of the plant defense methods that can make it difficult for mites to eat. This process may lead to a decline in the quality of development for T. urticae and reduce the quality and size of their eggs. This favors predatory mites and may explain why less time is required to feed eggs on beans treated with B. velezensis.

B. velezensis can develop bioactive secondary metabolites that benefit the plant. The biosynthetic arsenals of B. velezensis are more powerful and diverse than other Bacillus species including B. subtilis (Fazle Rabbee and Baek 2020). The handling time in the B. velezensis treatment was significantly lower than the B. pumilus treatment. This finding suggests that B. velezensis had a more positive effect on the kidney bean's defense mechanism against T. urticae. This parameter was also significantly lower than 3-pentanol and methyl jasmonate.

Based on these results, both B. velezensis and methyl salicylate can increase the P. persimilis efficiency by decreasing its handling time and increasing its maximum predation rate. Based on their negative impact on the T. urticae life table parameters, they can be used bilaterally to reduce the population of two spotted spider mites while increasing the efficiency of predatory mites. We recommend further research to determine the optimal application of these findings on a larger scale.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Department of Plant Protection, Razi University, Iran, for supporting this project.

References

- Cedola C.V., Sanchez N.E., Liljesthrom G.G. 2001. Effect of tomato leaf hairiness on functional and numerical response of Neoseiulus californicus (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol., 25: 819-831.

- Choi H.K., Song G.C., Yi H.S., Ryu C.M. 2014. Field evaluation of the bacterial volatile derivative 3-pentanol in priming for induced resistance in pepper. J. Chem. Ecol., 40: 882-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-014-0488-z

- Cna′ani A., Seifan M., Tzin V. 2018. Indole is an essential molecule for plant interactions with herbivores and pollinators. J. Plant Biol. Crop. Res., 1:1003. https://doi.org/10.33582/2637-7721/1003

- De Boer J.G., Dicke M. 2004. The role of methyl salicylate in prey searching behavior of the predatory mite Phytoseiulus persimilis. J. Chem. Ecol., 30: 255-271. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEC.0000017976.60630.8c

- Dicke M., Gols R., Ludeking D., Posthumus M.A. 1999. Jasmonic acid and herbivory differentially induce carnivore-attracting plant volatiles in lima bean plants. J. Chem. Ecol., 25: 1907-1922. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020942102181

- Dicke M., Sabelis M.W. 1988. How plants obtain predatory mites as bodyguards. Neth. J. Zool., 38: 148-165. https://doi.org/10.1163/156854288X00111

- Dicke M., Takabayashi J., Posthumus M.A., Schuette C., Krips O.E. 1998. Plant-phytoseiid interactions mediated by herbivore-induced plant volatiles: variation in production of cues and in responses of predatory mites. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 22: 311-333.

- Dicke M., van Beek T.A., Posthumus M.A., Ben Dom N., van Bokhoven H., De Groot A.E. 1990. Isolation and identification of volatile kairomone that affects acarine predator-prey interactions. Involvement of host plant in its production. J. Chem. Ecol., 16: 381-396. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01021772

- Glick B.R. 1995. The enhancement of plant growth by free living bacteria. Can. J. Microbiol., 41: 109-117. https://doi.org/10.1139/m95-015

- Gurevitch J., Hedges L.V. 2001. Design and Analysis of Ecological Experiments. In: Scheiner S.M., Gurevitch J. (Eds). Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, p. 187-195.

- Fang T., Ying-Ying F., Jian-Ren Y. 2015. The effect of methyl salicylate on the induction of direct and indirect plant defense mechanisms in poplar (Populus × euramericana ′Nanlin 895′). J. Plant. Interact., 10(1): 93-100. https://doi.org/10.1080/17429145.2015.1020024

- Farazmand A., Fathipour Y., Kamali K. 2012. Functional response and mutual interference of Neoseiulus californicus and Typhlodromus bagdasarjani (Acari: Phytoseiidae) on Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae). Int. J. Acarol., 38: 369-376. https://doi.org/10.1080/01647954.2012.655310

- Fazle Rabbee M., Baek K.H. 2020. Antimicrobial activities of lipopeptides and polyketides of Bacillus velezensis for agricultural applications. Molecules, 25(21): 4973. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25214973

- Hassel M. 2000. The Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Host Parasitoid Interactions. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- James D.G. 2003. Field evaluation of herbivore-induced plant volatiles as attractants for beneficial insects: Methyl salicylate and the green lacewing, Chrysopa nigricornis. J. Chem. Ecol., 29: 1601- 1609.

- Juliano S.A. 2001. Nonlinear curve fitting: predation and functional response curves. In: Scheiner, S.M., Gurevitch J. (Eds.). Design and Analysis of Ecological Experiments. New York, Oxford University Press, p. 178-196.

- Kessler A., Baldwin I.T. 2001. Defensive function of herbivore induced plant volatile emissions in nature. Science, 291: 2141-2144. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.291.5511.2141

- Khan Z.R, James D.G., Midega C.A.O., Pickett J.A. 2008. Chemical ecology and conservation biological control. Biol. Control, 45: 210-224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2007.11.009

- Kloepper J.W., Ryu C.M. 2006. Bacterial endophytes as elicitors of induced systemic resistance. In: Schulz B., Boyke C., Sieber T. (Eds.) Microbial root endophytes, Berlin, Springer-Verlag, p. 33-52 https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-33526-9_3

- Madhaiyan M., Poonguzhali S., Kwon S.W., Tong-Min S. 2010. Bacillus methylotrophicus sp. nov., a methanol utilizing, plant-growth-promoting bacterium isolated from rice rhizosphere soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., 60: 2490-2495. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.015487-0

- Meng, Q., Jiang H., Hao J.J. 2016. Effects of Bacillus velezensis strain BAC03 in promoting plant growth. Biol. Control, 98: 18-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2016.03.010

- Migeon A., Dorkeld, F. 2010. Spider Mites Web: A Comprehensive Database for the Tetranychidae. Trends in Acarol., 557-560. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9837-5_96

- McMurtry J.A., Croft B.A. 1997. Life-styles of phytoseiid mites and their roles in biological control. Annu. Rev. Entomol., 42: 291-321. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.291

- McMurtry J.A. 1982. The use of phytoseiids for biological control: progress and future prospects. In: Hoy M.A. (Ed), Recent Advances in Knowledge of the Phytoseiidae. Div. Agric. Sci. Univ. California. Publ., 3284. p. 23-48.

- Montazersaheb H., Zamani A.A., Sharifi R., Darbemamieh M. 2021. Effects of plant probiotic bacteria and herbivore-induced plant volatiles (HIPVs) on life table parameters of two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae) on kidney bean's attached leaves. Int. J. Acarol., 47(6): 520-527. https://doi.org/10.1080/01647954.2021.1957012

- Rasmann S., Agrawal A.A. 2009. Plant defense against herbivory: progress in identifying synergism, redundancy and antagonism between resistance traits. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol., 12: 473-478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2009.05.005

- Rogers D. 1972. Random search and insects' population models. J. Anim. Ecol., 41(2): 369-383. https://doi.org/10.2307/3474

- Royama T. 1971. A comparative study of models for predation and parasitism. Res. Popu. Ecol., 1: 1-90. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02511547

- Sabelis M.W., Van der Baan H.E. 1983. Location of distant spider mite colonies by phytoseiid predators: demonstration of specific kairomones emitted by Tetranychus urticae and Panonychus ulmi. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 33: 303-314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.1983.tb03273.x

- Seiedy M., Saboori A., Allahyari H., Talaei-Hassanloui R., Tork M. 2012. Functional Response of Phytoseiulus persimilis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) on Untreated and Beauveria bassiana - Treated Adults of Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae). J. Insect Behav., 25: 543-553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10905-012-9322-z

- Sznajder B., Sabelis M.W., Egas M. 2010. Response of predatory mites to a herbivore-induced plant volatile: genetic variation for context-dependent behavior. J. Chem. Ecol., 36: 680-688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-010-9818-y

- van Den Boom C.E.M., van Beek T.A., Posthumus M.A., De Groot A.E., Dicke M. 2004. Qualitative and quantitative variation among volatile profiles induced by Tetranychus urticae feeding on plants from various families. J. Chem. Ecol., 30: 69-89. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEC.0000013183.72915.99

- van Loon L.C., Glick G.R. 2004. Increased plant fitness by rhizobacteria. Pages 177-205 in: Sandermann, H. (Ed) Molecular Ecotoxicology of Plants. Vol. 170. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-08818-0_7

- Walzer A., Schausberger P. 1999. Predation preferences and discrimination between con-and heterospecific prey by the phytoseiid mites Phytoseiulus persimilis and Neoseiulus californicus. BioControl. 43(4): 469-478. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009974918500

- War A.R., Sharma H.C., Paulraj M.G., War M.Y., Ignacimuthu S. 2011. Herbivore induced plant volatiles. Plant Signal Behav., 6: 1973-1978. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.6.12.18053

- Wasternack C., Parthier B. 1997. Jasmonate-signaled plant gene expression. Trends Plant. Sci., 2: 302-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1360-1385(97)89952-9

- Xiao Y., Fadamiro H.Y. 2010. Functional responses and prey-stage preferences of three species of predacious mites (Acari: Phytoseiidae) on citrus red mite, Panonychus citri (Acari: Tetranychidae). Biol. Control, 53: 345-352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2010.03.001

- Zhuang X., Chen J., Shim H., Bai Z. 2007. New advances in plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for bioremediation. Environ. Int., 33: 406-413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2006.12.005

2022-09-14

Date accepted:

2023-06-27

Date published:

2023-07-04

Edited by:

Migeon, Alain

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

2023 Montazersaheb, Hosna; Zamani, Abbas Ali; Sharifi, Rouhallah and Darbemamieh, Maryam

Download the citation

RIS with abstract

(Zotero, Endnote, Reference Manager, ProCite, RefWorks, Mendeley)

RIS without abstract

BIB

(Zotero, BibTeX)

TXT

(PubMed, Txt)