Is Eriophyes mali Nalepa present in Italy?

Malagnini, Valeria  1

; Baldessari, Mario

1

; Baldessari, Mario  2

; Pedrazzoli, Federico

2

; Pedrazzoli, Federico  3

; Tatti, Alessia

3

; Tatti, Alessia  4

; Duso, Carlo

4

; Duso, Carlo  5

; de Lillo, Enrico

5

; de Lillo, Enrico  6

; Angeli, Gino

6

; Angeli, Gino  7

and Lewandowski, Mariusz

7

and Lewandowski, Mariusz  8

8

1✉ Fondazione Edmund Mach – Centro Trasferimento Tecnologico via E. Mach, 1 - 38010 San Michele all’Adige (TN) Italy.

2Fondazione Edmund Mach – Centro Trasferimento Tecnologico via E. Mach, 1 - 38010 San Michele all’Adige (TN) Italy.

3Fondazione Edmund Mach – Centro Trasferimento Tecnologico via E. Mach, 1 - 38010 San Michele all’Adige (TN) Italy.

4Scuola Universitaria Superiore IUSS Pavia, Palazzo del Broletto, Piazza Vittoria 15, 27100 Pavia, Italy & Center Agriculture Food Environment C3A, University of Trento and Fondazione Edmund Mach, Trento, Italy.

5Department of Agronomy, Food, Natural resources, Animals and Environment, University of Padova Via dell'Università 16 - 35020 Legnaro (PD), Italy.

6Dipartimento di Scienze del Suolo, della Pianta e degli Alimenti, University of Bari Aldo Moro, via Amendola, 165/a - 70126 Bari, Italy.

7Fondazione Edmund Mach – Centro Trasferimento Tecnologico via E. Mach, 1 - 38010 San Michele all’Adige (TN) Italy.

8Department of Plant Protection, Institute of Horticultural Sciences, Warsaw University of Life Sciences, ul. Nowoursynowska 159 - 02776 Warsaw, Poland.

2023 - Volume: 63 Issue: Suppl pages: 39-44

https://doi.org/10.24349/fgml-gv5cProceedings of the 9th Symposium of the EurAAc, Bari, July, 12th–15th 2022

Keywords

Abstract

Introduction

Eriophyoid mites (Acari: Prostigmata: Eriophyoidea) are obligate plant feeders, and most of them exhibit high levels of host specificity and adaptability (Lindquist 1996; Skoracka and Dabert 2010; de Lillo et al. 2018). They inhabit all plant parts except roots and can cause economically important damage to their hosts (Oldfield 1996; Westphal and Manson 1996). More than a dozen of eriophyoid species have been reported on apple plants (Malus domestica Borkh.) all over the world (Vidović et al. 2014; Amrine and de Lillo, unpublished database). Among them, the apple rust mite Aculus schlechtendali (Nalepa, 1890), a vagrant mite causing damages with high population densities (Duso et al. 2010), is the most widespread species in Italy.

In the last few years, leaf blistering was widely observed on apple leaves in commercial orchards of Northern Italy. These symptoms were reported for the first time in 2017 in Val di Non, which is one of the most important apple-growing areas of Northern Italy, and in several orchards in the Emilia-Romagna region. These damages were not compatible with those associated with the apple rust mite but looked like the blister galls described for the pear blister mite Eriophyes pyri (Pagenstecher, 1857) and the apple blister mite Eriophyes mali Nalepa, 1926.

The apple blister mite was described for the first time by Nalepa (1926) as Eriophyes pyri var. mali and was considered for a long time as a variety of E. pyri because of the morphological similarities and the production of identical symptoms on apple leaves (blister galls) (Vidović et al. 2014). Later, Liro and Roivainen (1951) changed the mite's taxonomic status and raised it to the rank of species [E. mali (Nal.) Liro (nov. comb.)]. In the late 50s, Burts (1970) described a new eriophyid species, E. mali Burts, 1970, which can be considered as a junior synonym of E. mali Nal. (Vidović et al. 2014), on apple samples collected in Washington (Pacific Northwestern USA). So far, E. mali has not been recorded in Italy, while the presence of E. pyri is quite common and well-documented for a long time (Canestrini 1890; Vidano et al. 1978).

In the present work, we carried out a molecular analysis to assess the identity of eriophyoid mites causing blisters on apple leaves and recently found in Northern Italy. As diagnostic structures for morphological analysis are not always enough for species discrimination and this often causes the misidentification of species (de Lillo et al. 2010), DNA-based approaches are often adopted to overcome this problem (Navajas and Navia 2010), like in the current case of eriophyoid mites collected on apple vs pear plants.

Material and methods

Eriophyoid mite specimens were collected from leaf blisters and buds of symptomatic apple and pear plants in the Trentino-Alto Adige region. Apple plants in three different orchards located in Trentino - Val di Non (Rumo, 46.433975°N and 11.028116°E, and Coredo, 46.356663°N and 11.083217°E) and Alto Adige (Vadena, 46.379604°N and 11.287893°E) and some pear plants in Alto Adige (Salorno, 46.241207°N and 11.205038°E) were sampled in 2020 and 2021. Symptomatic leaves and buds were observed under a dissecting microscope, and single individuals were collected using a brush with only one bristle and placed in a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube.

The DNA from single individuals was isolated using 5% Chelex® 100 (Bio-Rad) (Walsh et al. 2013). Each sample, after adding 10 µl of a solution of Chelex and proteinase K (95: 5), was incubated at 50 °C for 1h and then at 95 °C for 10 min. Five individuals were analyzed for each population.

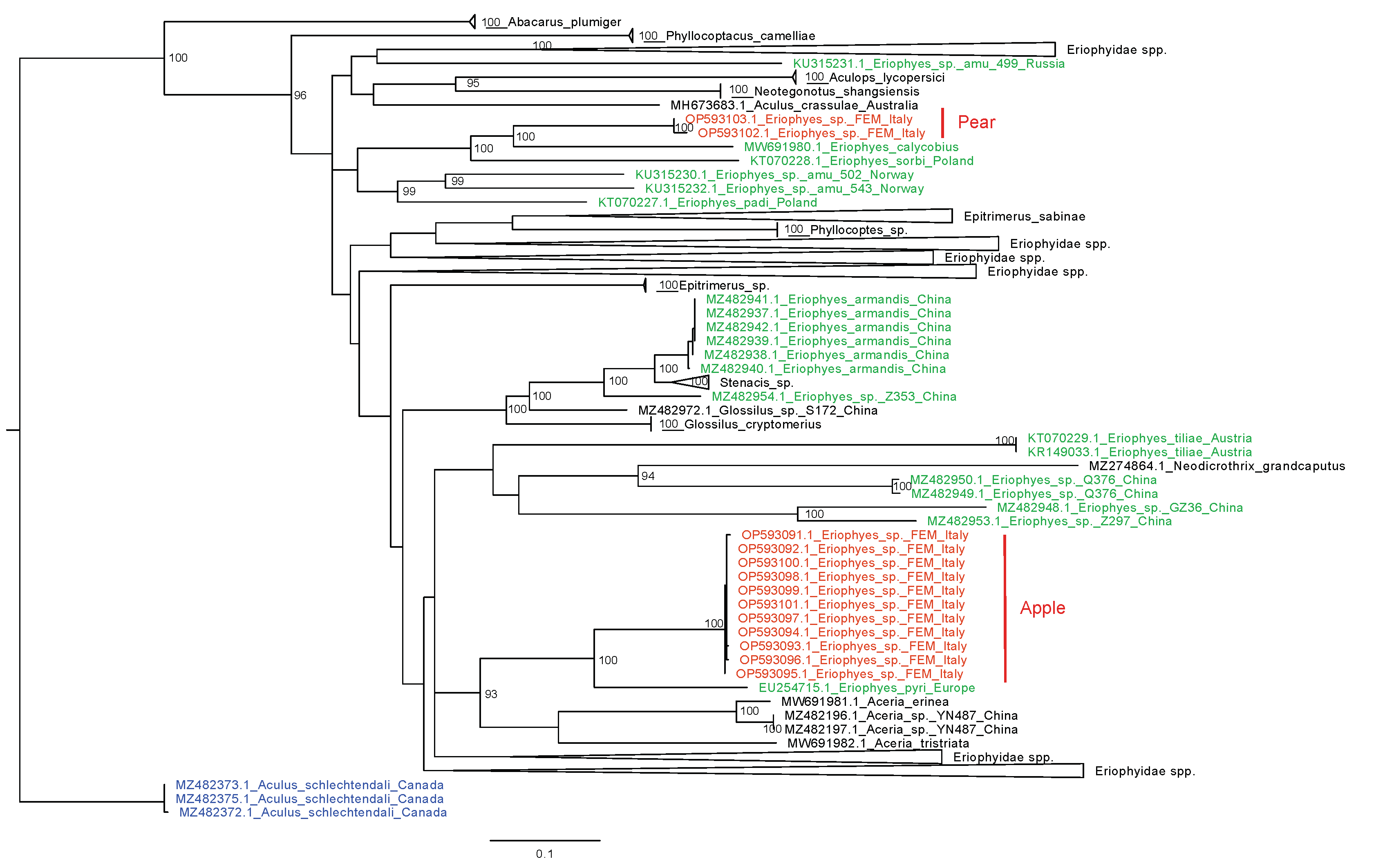

The cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COX1) gene was amplified with the primer pair LCO1490 and HCO2198 (Folmer et al. 1994). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions were as reported in EPPO (2021). PCR products, after purification with illustra ExoProStar1-Step (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK), were sequenced with the BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on an Applied Biosystems 3130 xl Genetic Analyzer (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Sequences were manually checked, and BIOEDIT software (Hall 1999) was used for corrections and alignments. Sequences obtained were deposited in the GenBank (NCBI) (accession numbers from OP593091 to OP593101 for samples from apple; OP593102 and OP593103 for samples from pear), and a search was conducted using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool). Then, we first built a dataset with a customed Python script retrieving 2,977 Eriophyidae COX1 sequences from Genbank. After aligning the sequences using MAFFT version 7.475 (Katoh and Standley 2013) with the ''adjust direction accurately'' option and cleaning the alignment with a customed Python script, an alignment with 662 positions was obtained. We analyzed a Maximum Likelihood (ML) exploratory tree with all 2,977 sequences and selected the clade that contained our newly sequenced species, removing the sequences that could cause a long branch attraction problem. The reduced dataset for the Eriophyidae family contained 304 sequences. We further trimmed the alignment obtaining a new alignment with 657 positions, and built the final ML phylogenetic tree, using IQ-TREE 1.6.12 (Nguyen et al. 2015) with the ''model selection'' option, 10,000 bootstrap replicates, and A. schlechtendali used as outgroup.

Results and discussion

Biological observations

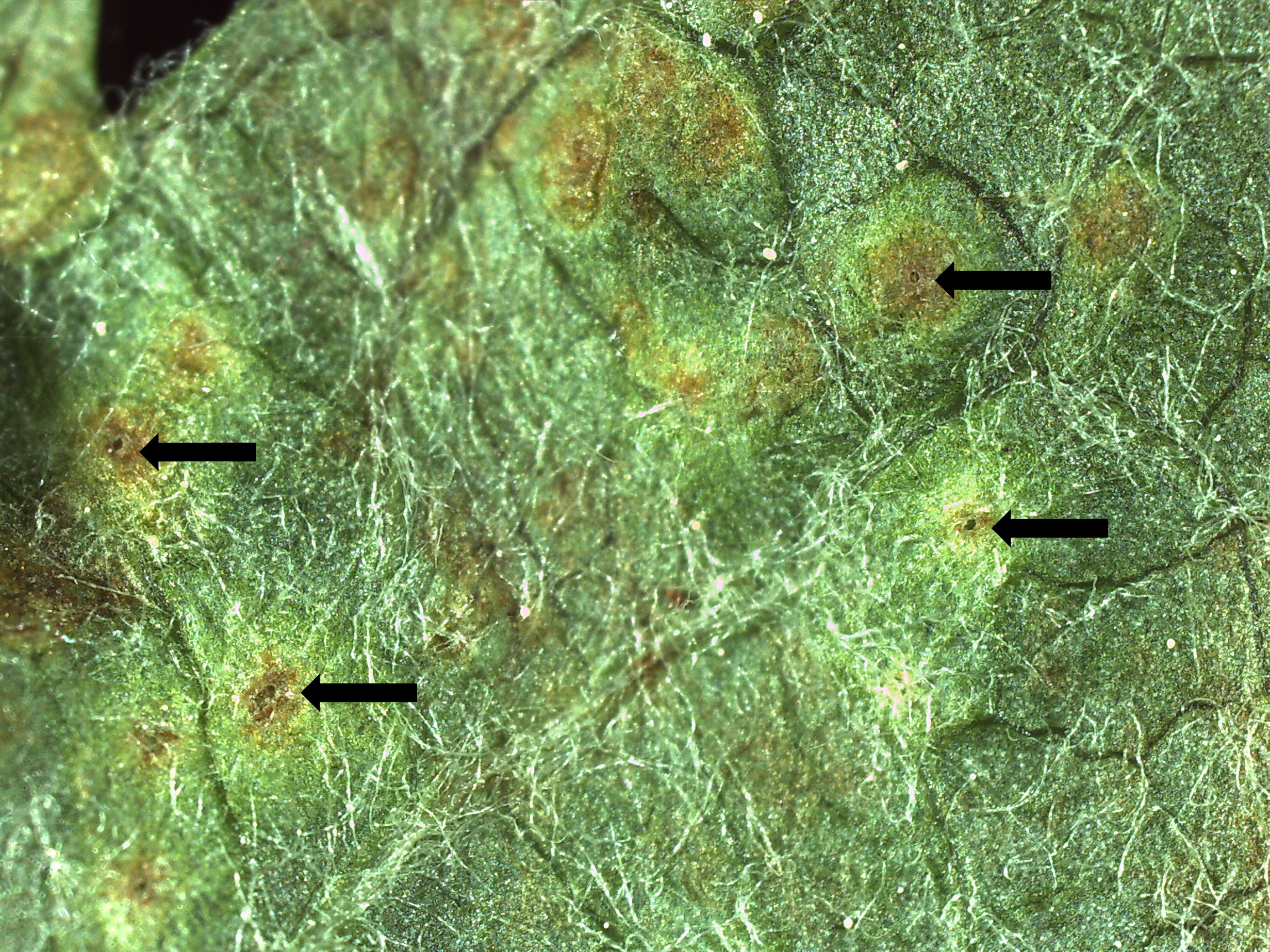

Early symptoms of the eriophyid mite presence, not ascribable to A. schlechtendali, were observed at the beginning of the spring. In this period, the upper surface of the leaves shows yellowish spots, while blisters, as well as the entry circular opening, are more visible in the undersurface (Fig. 1). Later in the season, blisters become larger and turn brownish, and the large under-epidermic cavities contain eriophyoids at different stages. These symptoms are similar to those described for apple blister mites (Vidović et al. 2014). Galls can also occur on the superficial layers of small fruits (Fig. 2). During the winter, eriophyoid mites can be found under the bud scales (Fig. 3).

Genetic data

The phylogenetic analysis indicates that eriophyoid mites collected from apple plants in different orchards of Trentino-Alto Adige belong to the same species and that mites collected from apple are different from those collected from pear plants. The identity score obtained blasting the COX1 sequences of apple mites against sequences of pear mites suggests even the possible presence of different genera (e.g., the GenBank identity score for OP593091 vs OP593102 is 79.97%).

This seems in contradiction with the preliminary morphological analyses (in verbis de Lillo) of samples collected from apple and pear plants. In fact, the typical diagnostic characteristics of the genus Eriophyes were observed in both mites, suggesting that they belong to the same genus.

These contradictory data highlight a very complex scenario inside the genus Eriophyes. For this reason, further molecular analyses, involving other molecular markers combined with morphological and ecological observations, are needed to better understand the identity of these samples.

The maximum likelihood tree calculated with IQ-TREE is shown in Fig. 4, where clades phylogenetically distant from the sequences of our samples are collapsed. The sequences submitted to GenBank as Eriophyes spp. are scattered across the phylogenetic tree and do not form a monophyletic group. According to this phylogenetic tree, the sister species of E. pyri from pear, with 100% bootstrap, is Eriophyes calycobius (Nalepa 1891) from Crataegus monogyna Jacq. (Rosaceae) (the GenBank identity score between OP593102 and MW691980 is 84.02%). Regarding apple eriophyoids, the sister species is E. pyri (accession number EU254715.1), with 100% bootstrap. This sequence is 444 bp long, and the low GenBank identity score with apple eriophyoids suggests different species (e.g. the identity score between EU254715.1 and OP593091.1 is 84.20%).

The species E. mali has been recorded in North America, New Zealand, the European part of Russia, and many European countries (Vidović et al. 2014), but so far not in Italy. If the eriophyoid samples collected on apple plants in the Trentino district were confirmed to be E. mali, this would be the first record for Italy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Manfred Wolf (Laimburg Research Centre) for collecting and providing mite samples collected on apple plants from Alto Adige.

References

- Burts E.C. 1970. Biology of blister mites, Eriophyes spp., of pear and apple in the Pacific Northwest. Melanderia, 4: 42-53.

- Canestrini G. 1890. Ricerche intorno ai Fitoptidi. Atti della Soc. Veneto-Trentina di Sci. Nat., 12(1): 1-26 + pls. 6-7.

- de Lillo E., Craemer C., Amrine J.W., Nuzzaci G. 2010. Recommended procedures and techniques for morphological studies of Eriophyoidea (Acari: Prostigmata). Exp. Appl. Acarol., 51(1): 283-307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-009-9311-x

- de Lillo E., Pozzebon A., Valenzano D., Duso C. 2018. An intimate relationship between eriophyoid mites and their host plants - A review. Front. Plant Sci., 9: 1786. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01786

- Duso C., Castagnoli M., Simoni S., Angeli G. 2010. The impact of eriophyoids on crops: recent issues on Aculus schlechtendali, Calepitrimerus vitis and Aculops lycopersici. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 51(1-3): 151-168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-009-9300-0

- EPPO 2021. PM 7/129 (2) DNA barcoding as an identification tool for a number of regulated pests. EPPO Bull., 51(1): 100-143. https://doi.org/10.1111/epp.12724

- Folmer O., Black M., Hoeh W., Lutz R., Vrijenhoek R. 1994. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol., 3(5): 294-299.

- Hall T.A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser., 41: 95-98.

- Katoh K., Standley D.M. 2013. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol., 30(4): 772-780. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst010

- Lindquist E.E. 1996. Chapter 1.1 External anatomy and systematics 1.1.1. External anatomy and notation of structures. World Crop Pests, 6(Eriophyoid Mites Their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control): 3-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1572-4379(96)80003-0

- Liro J.I., Roivainen H. 1951. Äkämäpunkit Eriophyidae. Suomen Eläimet. Poorvo-Helsinki: Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö. pp. 1-281.

- Nalepa A. 1890. Zur Systematik der Gallmilben. Sitzungsberichte der Kais. Akad. der Wissenschaften, Math. Wien, 99(2): 40-69 + 7 pls.

- Nalepa A. 1891. Genera und Species der Familie Phytoptida. Denkschriften der Kais. Akad. der Wissenschaften, Math. Wien, 58: 867-884 + 4 pls.

- Nalepa A. 1926. Zur Kenntnis der auf den einheimischen Pomaceen und Amygdaleen Lebenden Eriophyes-Arten. Marcellia, 22(1-6): 62-68.

- Navajas M., Navia D. 2010. DNA-based methods for eriophyoid mite studies: review, critical aspects, prospects and challenges. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 51(1): 257-271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-009-9301-z

- Nguyen L.T., Schmidt H.A., Von Haeseler A., Minh B.Q. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol., 32(1): 268-274. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu300

- Oldfield G.N. 1996. 1.4.3 Diversity and host plant specificity. World Crop Pests, 6(Eriophyoid Mites Their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control): 199-216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1572-4379(96)80011-X

- Pagenstecher H.A. 1857. Über Milben besonders die Gattung Phytoptus. Verhandlungen des Naturhistorisch-medizinischen Vereins, 1(2 (Bund 1857-1859)): 46-53.

- Skoracka A., Dabert M. 2010. The cereal rust mite Abacarus hystrix (Acari: Eriophyoidea) is a complex of species: evidence from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. Bull. Entomol. Res., 100(3): 263-272. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485309990216

- Vidano C., Arzone A., Meotto F. 1978. Alarming phytophagous in Piedmontese orchards today [Fitofagi preoccupanti di attualità in frutteti piemontesi]. Ann. dell′Accademia di Agric. di Torino, 120: 65-78.

- Vidović B., Marinković S., Marić I., Petanović R. 2014. Comparative morphological analysis of apple blister mite, Eriophyes mali Nal., a new pest in Serbia. Pestic. i fitomedicina, 29(2): 123-130. https://doi.org/10.2298/PIF1402123V

- Walsh P.S., Metzger D.A., Higushi R. 2013. Chelex 100 as a medium for simple extraction of DNA for PCR-based typing from forensic material. BioTechniques 10(4): 506-13 (April 1991). Biotechniques, 54(3): 134-139. https://doi.org/10.2144/000114018

- Westphal E., Manson D.C.M. 1996. 1.4.6 Feeding effects on host plants: Gall formation and other distortions. World Crop Pests, 6(Eriophyoid Mites Their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control): 231-242. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1572-4379(96)80014-5

2023-07-06

Edited by:

Nannelli, Roberto

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

2023 Malagnini, Valeria; Baldessari, Mario; Pedrazzoli, Federico; Tatti, Alessia; Duso, Carlo; de Lillo, Enrico; Angeli, Gino and Lewandowski, Mariusz

Download the citation

RIS with abstract

(Zotero, Endnote, Reference Manager, ProCite, RefWorks, Mendeley)

RIS without abstract

BIB

(Zotero, BibTeX)

TXT

(PubMed, Txt)